Stevanato Group (STVN) (Pt. 3)

The competition, the moat, and the risks

Hi reader,

Welcome to the third article on the Stevanato article series. If you have not read the first two articles, I recommend reading them before reading this one. In the first article, I discussed the company’s history and what it does. In the second article, I went over the financials and growth drivers. This article brings three other relevant topics: the competition, the moat, and the risks.

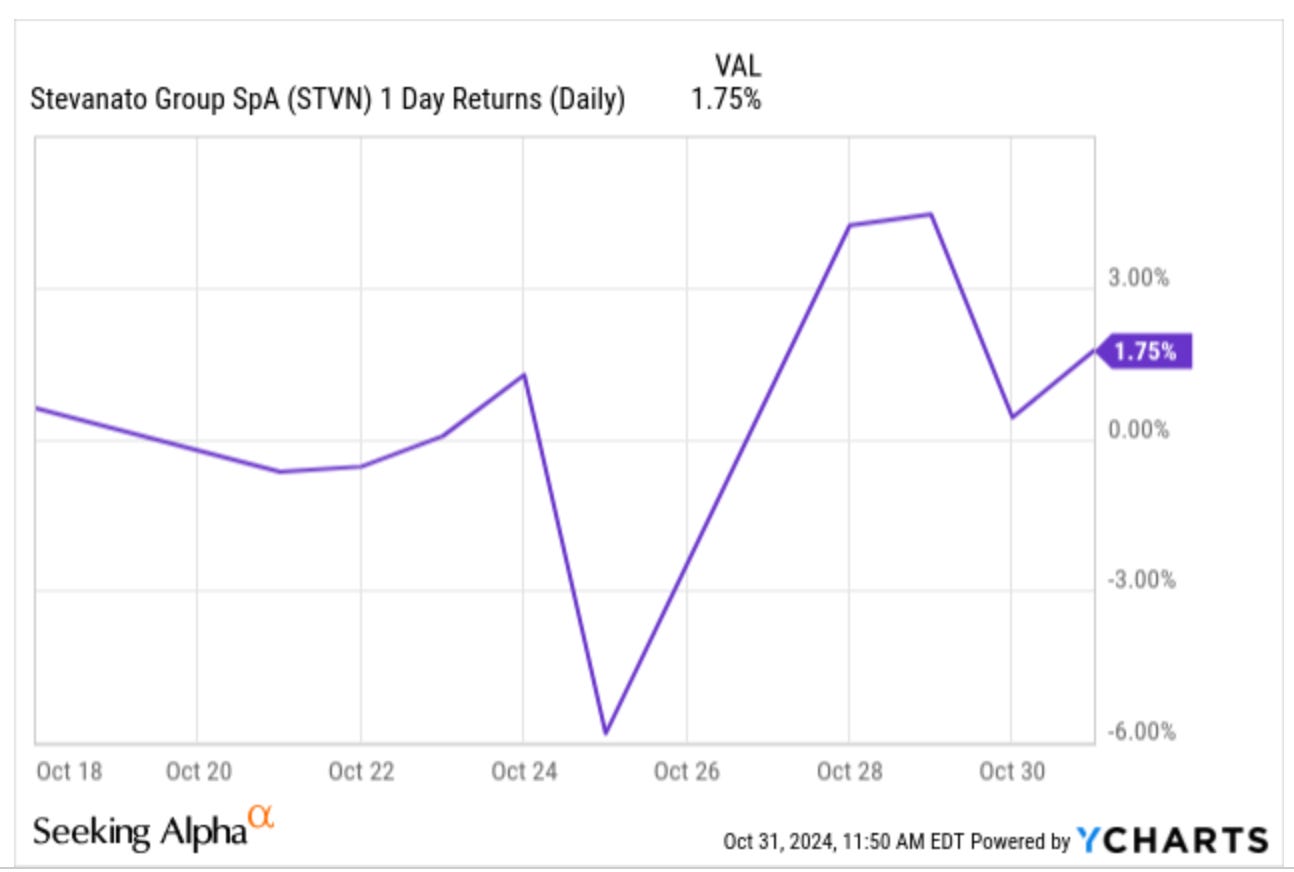

At the start of this article series I warned you that Stevanato could be a pretty volatile stock due to its tiny float, and it’s not disappointing. I released that article on October 18th, and the stock has seen some pretty wild swings since then:

Nothing unexpected and nothing that should worry us much.

Without further ado, let’s jump right into the article.

The Competition

Competition is not a straightforward topic for Stevanato because, despite several competitors in the industry, competition seems quite rational, and the market structure seems oligopolistic.

Just so you get a sense of the competitive environment, I would note that Gerresheimer, Schott Pharma, and Stevanato recently signed a strategic partnership to bring RTU (ready-to-use) products to market. I don’t know many industries where competitors sign strategic alliances:

The reason behind the strategic alliance is that it’s a win-win because these companies will see their portfolios transition to higher-margin and higher ASP (Average Selling Price) products like HVPs.

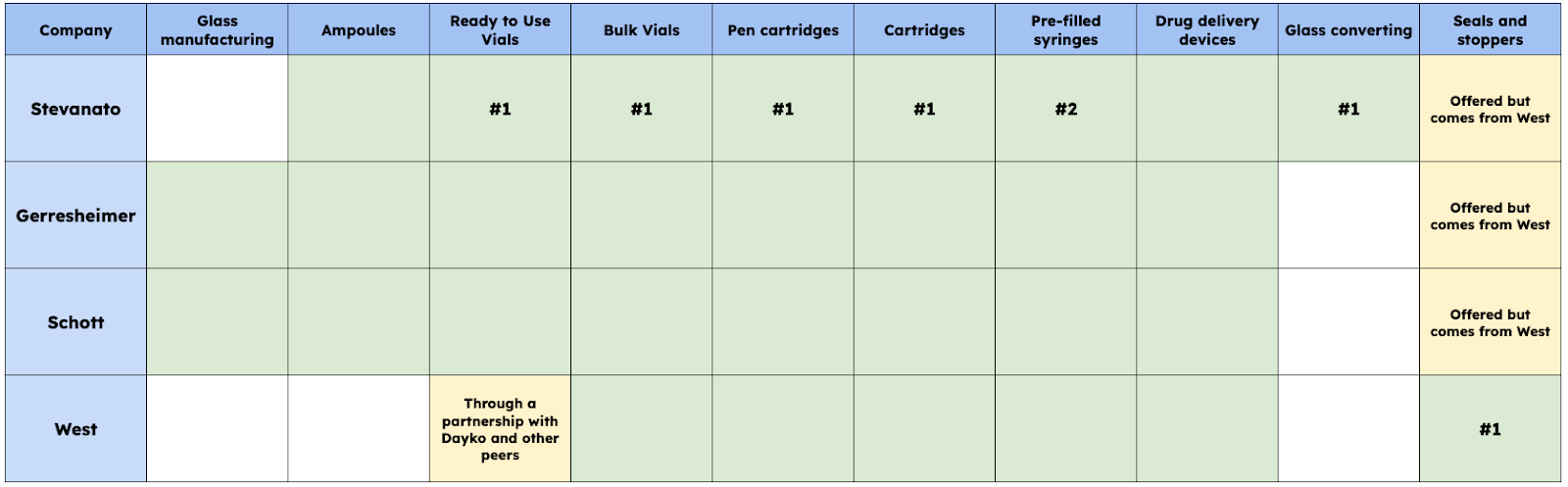

Stevanato has three main peers in the industry: West Pharmaceuticals, Schott Pharma, and Gerresheimer. These four companies (the three I just mentioned plus Stevanato) make up most of the volume in the drug containment industry. Their portfolios are pretty similar but have some differences. I built this table comparing where the different companies are present and where Stevanato and a few others lead:

Some comments on the table above…

Most companies offer a relatively comprehensive portfolio of drug containment solutions, and all are present in the drug delivery space.

West and Stevanato have a “hole” in their portfolio in that they don’t manufacture the glass that is later transformed into containment solutions. Stevanato has long-term agreements with its providers (Schott, Corning, NEG, and Nipro)

Stevanato is the only company involved in glass converting and holds leadership positions across many containment types.

West basically has a “monopoly” in seals and stoppers. Other companies also offer these products, but they tend to be West’s products. Something similar happens with West and RTU vials; they do offer them, but products are from the other providers or Dayko (a Japanese producer with which West has a partnership)

The only thing I want you to take away from this section is that competition seems rational because the ongoing shift in the industry benefits all players. It’s in everyone’s interest to help the industry transition to ready-to-use (high-value) products. To be honest, the different players don’t seem too worried about competing fiercely against each other. In the words of Stevanato…

We are not searching for shaving share in terms of competition, but we are focused on the expansion of high-value solutions to follow the growth of the emerging part of the market that is linked to biologics.

This benevolent competitive environment makes sense because the biologics/injectables market is growing at a good pace, and the transition to HVPs is providing some additional growth. In short, everyone is growing, so there’s basically no need to compete fiercely (the strategic alliance I discussed above shows just this). This is our current scenario, but we must monitor how it evolves as capacity comes online.

One might fear that new players might enter this industry to destabilise the oligopolistic environment. I believe this is pretty unlikely, and it’s a risk I’ll put to rest in the next section: there are very high barriers to entry in the industry.

Another thing to consider here is that there tends to be some kind of dual sourcing, more so after the current supply crunch suffered during the pandemic. Customers might try to spec in several containment solutions into their drug filings to attain a flexible supply chain. This applies primarily to new drugs.

The Moat

Stevanato has several components to its moat, although I must say that most of these components are industry-specific rather than company-specific. I’ll go through these first and then explain some Stevanato-specific competitive advantages. Most of the industry-specific advantages result in high switching costs and strong entry barriers for new competitors.

Regulatory barriers (industry)

Stevanato (and most companies in the industry) used to be “simple” suppliers of containment products, but they are now transitioning into partners selling solutions. The reason is the increased complexity of the drugs. This transition has several implications, the most important being that the company is now present during the early stages of drug discovery, helping its customers choose/design the best containment solution and drug delivery device early on.

Being early is important because the containment solution eventually gets spec’d into the drug. Regulators consider the containment solution to be a “part of the drug” because it’s in direct contact with it. This means that once a containment solution has been approved with a drug, the customer has two choices…

Use the containment solution throughout the life of the drug

Switch the containment solution after approval, incurring in lost time going through a new approval process

According to Stevanato and based on what I’ve heard from several industry experts, customers tend to go for the former…

When a customer chooses to work with 1 of our products, we are with them for the entire life cycle of the treatment.

These are very similar market dynamics to those of Danaher. Once a biologic has been approved using a given manufacturing method, it must be used forever or undergo a new approval process. The reason is that any change in the process or the containment solution could potentially alter the drug and, therefore, should be “re-tested.”

This also has implications for biosimilars. Some investors are worried that biosimilars (being more affordable biologics) might opt for a cheaper containment solution (i.e., downgrade). Stevanato disagrees and believes that time is money for biosimilars, so they will most likely stick with the original containment solution:

The fact that we are already registered in the originator will help us to give a very strong reference both in product and service and processes. Biosimilars tend to copy the type of drug packaging that the originator has in terms of performances and in terms of specification.

This is no coincidence, as the FDA and EMA (the US and European regulators, respectively) consider it in their biosimilar guidelines. These regulatory agencies establish that biosimilars must demonstrate similarity in safety, efficacy, and quality to the original biologic, including aspects related to containment and packaging. Regulatory bodies don’t prohibit biosimilars from choosing a different containment solution, but they do establish they must comply with similar standards. Biosimilars likely opt for the same containment solution as the original biologic to avoid all the hassle that comes with a change which probably costs the company quite a bit of money.

Reputation and pharma conservativeness (industry)

Two other things that make the entry of a new player into the market challenging are reputation and conservativeness from the pharma companies. Let's start with the former. Stevanato and its peers have been operating in the primary containment industry for decades, so they have a reputation for safety and know-how, which serves well with pharma companies and regulatory bodies. Just a quick heads up on some dates…

Stevanato entered the industry around 1970

West Pharmaceuticals entered the industry around 1940

Schott Pharma entered the industry in 1911

Gerresheimer entered the industry in 1987

To this, we must add that pharma companies are inherently reluctant to change and very risk-averse. Pharma is a business with many sunk costs (both in time and money) that must be recovered by launching several successful products. Considering that only 10-20% of drugs that enter the clinical stage make it to commercialization, I can understand why they would be reluctant to “bet” on a newcomer for a critical product like the containment solution. There’s a lot of money at stake, and one would unlikely risk it for a couple of cents per containment solution. This brings a bit of the “nobody gets fired for hiring IBM” vibes.

Pharma conservativeness, together with the regulatory barriers, make this a business that’s not prone to disruption risks. In the words of an industry expert…

In our industry, there is no breakthrough technology; there’s only evolution.

Mission-criticality and a low portion of the overall budget (industry)

Two characteristics that are always worth looking for are mission-criticality and how much the product makes of the total cost base of the customer. Both in tandem create significant switching costs because the customer has no incentive to look for a competing solution even after recurring price increases. These principles have cemented the success of industries such as VMS (Vertical Market Software), and they also stand true in the fill & finish industry.

Stevanato’s products are mission-critical because they are in direct contact with the drug entering a patient’s body. If there’s any problem with the containment solution, Stevanato and the pharma company might face significant legal issues. These products also make up a low portion of the end-product costs, not when considering the end-product as a single dose of the vaccine, but considering all the costs of drug development. Pharma companies also care dearly about safety and speed to market, so it’s unlikely that price will be their primary consideration anyway.

It is worth noting that Stevanato and its peers are not “milking” their customers through price increases. The switch to HVPs comes at a cost for a pharma company, but they also get more value, so it should not be considered a price increase per se because more value is being delivered through the outsourcing of activities like washing and sterilisation. Price increases in the industry tend to be in the 1%-3% range.

Vertical integration and an E2E solution (Stevanato)

As discussed throughout the first two articles, Stevanato possesses something that no other peer possesses: it’s vertically integrated and can offer an E2E solution.

Stevanato is the market leader in glass converting, the process used to convert glass tubes into containment solutions. No other peer has similar technology and depends on Stevanato (and other providers) for it:

We are the market leader in glass converting, the critical technology for manufacturing containment solutions. Owning this technology represents a key competitive advantage that is unique to Stevanato.

Stevanato is also the only company able to offer an E2E solution to its customers. This E2E solution comprises three things:

The containment solution

The device where the drug will be administered in

The assembly and packaging systems used to join both

In the words of a Stevanato customer…

Stevanato can sell the customers the glass, the machine to inspect the product filled with the drug, can sell the machine to assemble the devices, and so on. The company has a more integrated portfolio compared to other competitors in the glass industry.

Most peers have #1 and #2, but none have the three (besides Stevanato). There’s no denying that Stevanato is vertically integrated and can offer an E2E solution, but why should we assume this is a competitive advantage? The first reason I’d note is that pharma companies are trying to streamline and simplify their businesses, and an E2E solution helps them do just that by partnering with a single supplier for all of their needs. The second reason I’d note is that West Pharmaceuticals has sort of given some hints regarding E2E being the right strategy. This is from the Q4 2019 earnings call:

Well, one thing I can comment there is that we’ll continuously look at the landscape and see what assets, if available, would make sense to be part of West that enables us to provide a more comprehensive solution to our customers. So I can’t comment any further about any of the specific targets, but we are constantly looking at the horizon, saying what would be the right fit with West.

Stevanato has taken quite the opposite route regarding M&A due to the company already having a comprehensive portfolio:

We see no major gaps in our portfolio, but we believe there are markets that are natural extensions of our current core competencies.

Long-term orientation (Stevanato)

Stevanato’s family ownership is also a competitive advantage, especially when large investments in long-term capacity are required. Family ownership brings two advantages:

It allows management to think long-term without having to worry about what shareholders will think

Considering management’s stake in the business, minority shareholders can be confident that management believes it’s the best use of capital

The Risks

Stevanato, like any other company, is exposed to several risks.

A short track record

Stevanato IPOed in 2021, so there’s no long track record to judge management’s abilities or the company’s “normalized” financials. There’s always a risk with these types of companies because one can’t assess management’s credibility due to the absence of benchmarks. The good news is that most of the family’s net worth is tied to the business; therefore, one can think they have no incentive to be misleading.

The aggressive capacity expansion plan (overcapacity?)

Some investors are worried about the massive capacity expansion plan eventually creating a situation of overcapacity if demand does not materialize as expected. Let’s not forget that Stevanato has been spending north of 30% of sales in Capex (with maintenance Capex being around 3%). If demand doesn’t materialize, many fear it might translate into excess capacity and, therefore, lower margins going forward due to underutilization. It’s a reasonable concern, but I think several things should tame these fears.

First, this capacity expansion plan is demand-driven and governed by multi-year agreements, which include cost pass-through provisions. This means Stevanato has somewhat high visibility on future demand. The only problem here is that its customers might also get the demand environment wrong. Therefore, these multi-year agreements might not hold because they do not contain minimum purchase requirements.

Secondly, the company’s capacity expansion plan is modular. Stevanato is past the peak of capacity additions, which should moderate to a steady state around 2027. From then on, management expects to invest 10% of sales into Capex, of which 70% will be destined to growth Capex (7% of sales). However, this Capex will be flexible, and the company can take it as low as 3% if there is no demand. This should somewhat tame the fears of a capacity overbuild once we get to 2027.

Also worth noting is that some of this demand is not incremental but replacement demand. Most of the capacity being built is for HVPs, which should be partly incremental, but that should also serve to convert some of the existing volumes.

Anyways, it’s undoubtedly a risk, especially since management teams (including those of Stevanato’s customers) tend to be more optimistic than pessimistic. The secular growth drivers are there, and the company has taken a modular approach, so I think it will work out fine in the long term. Also worth noting is that management is compensated based on ROIC, and therefore, they are aligned in this regard with shareholders.

Low-float

Low float comes with two risks, albeit one is not a risk from the POV of a long-term investor. The first risk, which I imagine you’ve already experienced, is that the stock can be pretty volatile due to this low float.

The second risk related to the low float and arguably more relevant to long-term investors is that the family might be incentivized to take the company private at some point. If the stock remains cheap and they believe that being publicly traded is too much hassle, why not take the company private again? The Stevanato family owns today 83% of the company, so they would surely have the means to take it private if they wished. This is indeed a risk, but I don’t see it happening for several reasons.

First, they have built a very strong board of directors (including Don Morel, former West Pharmaceuticals CEO), which would not be very consistent with wanting to take the company private over the short term. Secondly, the Stevanato family has laid its ambitions as a Stevanato shareholder…

The Stefano family wants to remain the anchor shareholder of the company.

Rise of non-injectable biologics

As discussed in the prior article, Stevanato is exposed to a growth driver similar to Danaher's: the rise of biologics. However, while Danaher is exposed to any kind of biologic irrespective of its administration form, Stevanato is primarily exposed to injectables (which is the form biologics tend to be administered in).

There’s a risk that, to increase compliance and penetration, the industry will look for ways to administer biologics through other methods, such as oral administration. There are certain roadblocks here because the digestive system tends to kill the protein in a biologic, reducing its efficiency.

The industry is researching ways to make this possible, but we’ll unlikely see it come true over the next 10 years (at least). The main reason is that to administer orally, the drug manufacturer has to consider this as early as the drug discovery process. Because the drug development process typically takes north of 10 years, we should already be seeing these in the pipeline:

Although research is very active, the oral route represents a very small share of the biomedical products under development and should, therefore, remain minor in the next ten years.

There have been discussions around oral GLP-1s and their impact on the fill & finish industry, considering these currently make up a significant portion of the business. Stevanato’s management believes oral GLP-1s will make up around 30% of the total market in the future but argued they are being pretty conservative with their estimates:

In our industrial plan, we have captured only what is rated with contract that we have with GLP-1 in order to really be safe. In our 5, 10-year vision, we have put the market share that oral can have sort of prudence of 30% to 35%.

That we know that is extremely safe compared to the estimation of the expert that they are taking maybe the role of the peers more around 10% to 15%, but we want to not underestimate this.

Oral GLP-1s were achieved using a procedure (permeation enhancers) that is not applicable to all biologics. To this, we must add that the efficiency of oral GLP-1s promises to be lower than those administered via injectables…

The bioavailability of Rybelsus (i.e. the proportion of the active ingredient absorbed by the patient in relation to the total quantity contained in the biomedicine) is only 1%, compared to more than 50% for its equivalent administered subcutaneously.

Source: Alcimed

This means that the quantity of active ingredient that needs to be manufactured to achieve the same result is significantly higher in oral administration than for an injectable. While low efficacy might be acceptable for GLP-1s used for obesity, this might not be acceptable for diseases where efficacy is non-negotiable. There’s no denying that compliance is much higher with oral drugs, but the industry is also looking for alternatives inside the injectable world. A clear example is drug delivery devices to be administered by patients at home.

In the meantime, keep growing!

Read part 4 here 👇🏻