Stevanato Group (STVN) (Pt.1)

A High-Quality Family Business Swamped in Opportunity Cost

Hi reader,

I have studied various companies since adding the last company to my portfolio, but none convinced me like the one I will discuss in this article.

I imagine most of you will not have heard about this company, but you have probably heard about one of its competitors: The company I am adding to my portfolio is a “newcomer” to the stock market, but one of its main peers isn’t and has achieved a total return CAGR of 21% over the last decade. The company I am profiling today is significantly smaller than this peer (with a market cap just under $6 billion), and make its debut in financial markets in 2021 (good timing). However, I think it’s an outstanding company with a bright future. Despite the company being a newcomer to financial markets, it’s not a young company, having a 70-year long history. The company did not IPO previously because it did not need it; it has been profitable for a long time and is (still) family-owned.

I imagine you will not completely understand all the points that I am about to list below (at least not until you read the entire article series), but I thought it would be a good idea to share a brief investment thesis in the first article. Much more detail will be shared in coming articles, but I believe these points pretty much sum up the investment thesis:

The company operates in an oligopolistic industry made up of rational players (three competitors have recently signed an “alliance” to take their products to market).

The company’s products make up a low portion of their customers’ costs and are mission-critical. They are also protected by regulatory barriers.

The industry is expected to grow significantly over the coming years, with a good portion of this growth coming from higher-margin sources.

It’s family-owned and operated (third generation), and management exhibits clear traits of long-term thinking.

The company’s compensation structure is based on ROIC and organic growth, which is not a coincidence considering they aim to replicate winning formula of its main competitor aided by non-other than its former CEO (who serves on the board)

The company is currently undergoing a significant Capex plan to prepare for future growth, but the capacity expansion is demand-driven and based on multiyear agreements with customers (so there’s high visibility).

The stock is currently swamped with opportunity costs because it’s facing several temporary headwinds (besides the capacity expansion plan). I must add that despite an almost $6 billion market cap, it’s pretty much out of reach for many funds due to its tiny float (the family still owns a considerable chunk of the company).

The company undoubtedly has an optically high multiple, but its true profitability is currently being masked by temporary headwinds. Growth has significantly stalled recently, with 2024 expected to be a transition year. The company was a clear pandemic beneficiary (more in terms of stocking than Covid) but I am confident that growth will return.

Without further ado, let’s jump right into the company’s history.

Stevanato’s story

The roots of Stevanato trace back more than 70 years when, in 1949, Giovanni Stevanato (the grandfather of the current CEO) founded Soffieria Stella, a specialty glass manufacturer in Venice.

Franco Stevanato, the current CEO, tells the story of how he used to attend his grandfather’s factory on Saturdays when he was a kid:

When I was a child, my grandfather often used to take me to the company on Saturday morning. I was always very excited for this. I remember I used to visit the production floor and then go to the engineering department where we used to develop a new idea for the glass forming technology. These were the two things he used to love the most.

And I learned a lot from my grandfather, and it's still today one of my model of example in my life because still today, I used to go on Saturday morning in the production to talk with the people because what I really learned from my father that the human relationship with the people Is the key driver for the success of the company.

Stevanato was initially specialized in the “art of bottle blowing,” the fancy way of saying that it manufactured glass bottles. Soffieria Stella operated until 1959, when it closed its doors to give birth to Ompi, a company specializing in glass primary packaging and which would be based in Piombino Dese (Padua, Italy), home of Stevanato to this day. Piombino Dese is a very small village (population under 10k) next to Venice:

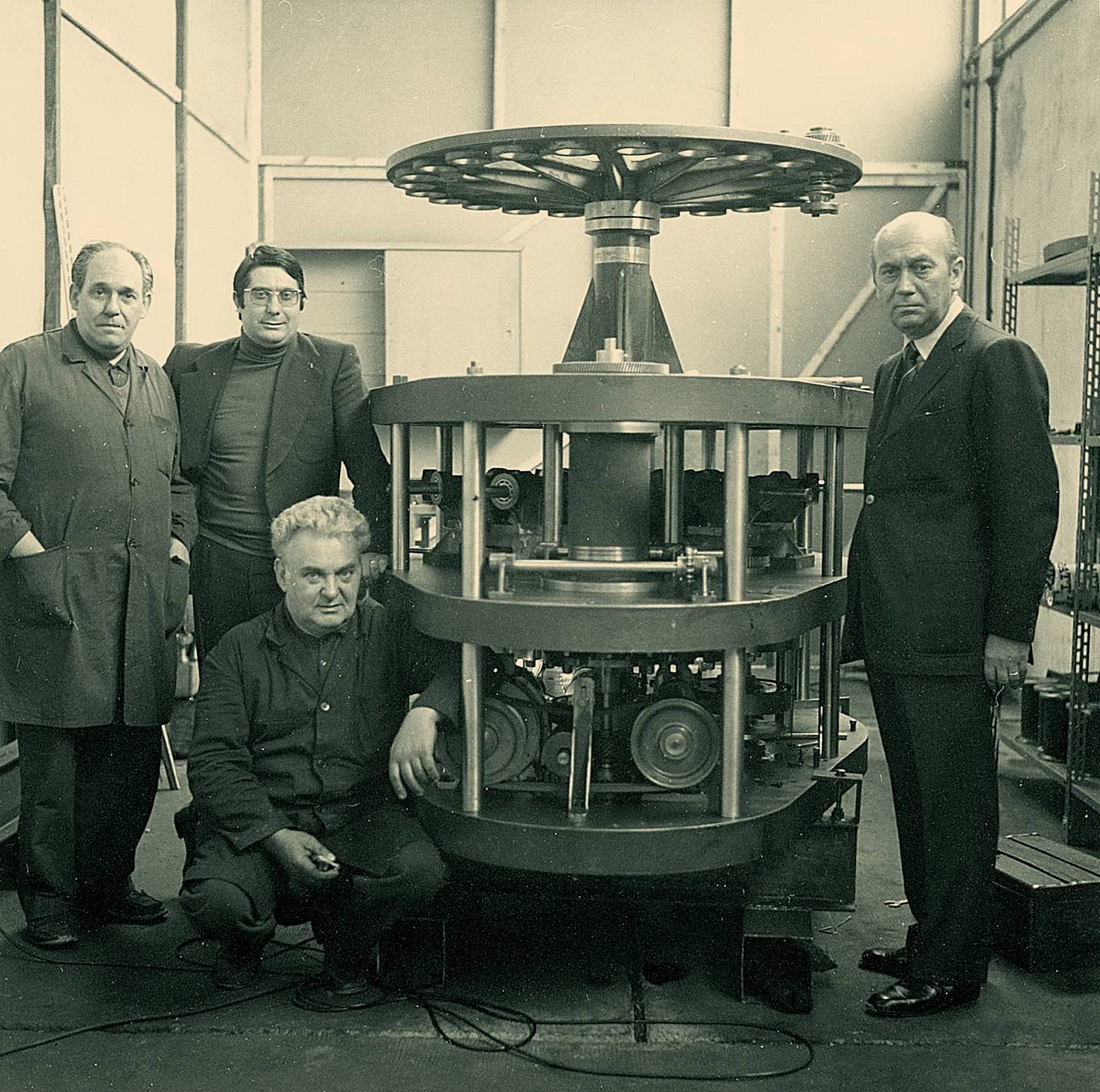

The most important milestone for the company took place in 1971 when the Stevanato family founded Spami. Spami would manufacture the glass-forming technology that allows Stevanato to manufacture its high-quality containers even today. Today, this glass-forming technology is a standard in the industry, and none of its peers own something similar. The technology basically consists of heating glass tubing at the right temperature to mold it into vials, syringes, or other types of containers…

Stevanato had started selling earlier to the healthcare industry, but having its own glass-forming technology was a key advantage to continue doing so and eventually specializing just in this industry.

The company continued its expansion by purchasing several companies like Alfamatic (1993) and Medical Glass (2005). The latter was quite relevant because it marked Stevanato’s first foray into international markets. Medical Glass was based in Slovakia, and its manufacturing plant is still in operation. The 2000s, however, brought even better news. In 2007, Stevanato started working on a project that would eventually give birth to the Ez-Fill Platform in 2008. The Ez-Fill Platform would allow Stevanato to sell ready-to-use vials and cartridges, which are still considered the company's most relevant growth driver.

2007 was also a year where Stevanato continued to build its engineering portfolio through the acquisition of Optrel. Optrel specialized in inspection machines for glass containers, a technology that Stevanato uses in-house and sells to its customers. The road the management team was taking was evident: vertical integration.

In the 2000s, the company entered two additional geographies: Mexico (2008) and China (2012) through greenfield investments. China does not make an important part of Stevanato’s revenue today, but management expects this to change in the future (with the rise of biosimilars).

Management decided to complement its Optrel acquisition in 2013 by acquiring InnoScan, a manufacturer of high-speed inspection systems for complex drugs. Again, the vertical integration playbook. It’s worth noting that, as Stevanato made all these acquisitions, peers continued to specialize with no signs of wanting to vertically integrate. As I’ll discuss briefly later on, this might be starting to change.

The company eventually ended its “acquisition spree” in 2016 after acquiring two additional companies:

SVM: specialized in assembly and packaging equipment of medical devices

Balda: specialized in plastic development and manufacturing for diagnostic consumables, delivery systems, and medical components

As Stevanato was a private company when it conducted these acquisitions, disclosure is limited, but they have definitely allowed the company to offer end-to-end services to its customers. More on this later.

The company has since focused on expanding internationally through greenfield investments and has invested considerable amounts into its capacity until ending with 15 sites in 9 countries:

What Stevanato does

The value chain of biologic manufacturing

Before going directly into what Stevanato does in detail, I thought it would be a good idea to discuss where the company fits in the “pharma value chain.” I also own Danaher, which fits in the same value chain but in a different step. Danaher is directly involved in manufacturing the drug through its biotechnology segment. Stevanato is present in this same value chain but at a later stage.

If I were to divide the value chain of a biologic into four big groups to make it understandable (very summarized, I know), it would look something like this:

Research + clinical trials: the process from initial research until the FDA approves the drug for commercialization. Not many drugs make it to the end of this process, which is why pharma companies tend to have so many open projects open at any given time and why they tend to make so much money on those that do work. Danaher participates here but to a lesser extent than in the next step.

Scale manufacturing: manufacturing the already approved drug, the liquid that will go into the primary container. This is where Danaher is present through its biotechnology segment, as it’s a key supplier in the bioprocessing process (this is the process through which companies manufacture biologic drugs).

Fill & Finish: the primary container is manufactured and sterilized and the drug is subsequently introduced. This is where Stevanato participates.

Distribution: the drug is distributed and used in patients.

This is a very simplified process, but it should help you understand that Danaher and Stevanato participate in two different sections of the same value chain. As you’ll learn in the next article, this means that, to an extent, they are also exposed to similar growth drivers and are going through similar challenges today.

A cautionary note here…the fact that Stevanato makes pretty much all of its revenue from the third step doesn’t mean it doesn’t actively participate in the process earlier. Customers must start thinking about the containment solution in the pre-clinical stages, so Stevanato acts to some extent like a consultant who helps its customers select the most appropriate solution:

We are moving from being a simple supplier of a product to being a partner in the development of a new medicine. With some customers, we are starting to work really in the preclinical stage.

How does Stevanato participate in the third step?

Stevanato manufactures primary containment solutions for the healthcare industry. The company is organized into two reportable segments, which, in my opinion, do a pretty good job of clearly separating its two most relevant activities:

Biopharmaceutical & Diagnostics Solutions (aka. BDS)

Engineering

Both segments operate as the picks & shovels of the pharma industry, although their revenue mix is very different. Let’s look at them individually.

The Biopharmaceutical & Diagnostics Solutions segment - 81% of 2023 revenue

Stevanato’s biopharmaceutical & diagnostics solutions segment can be further subdivided into three subsegments…

Drug Containment Solutions

Drug Delivery Systems

In-Vitro Diagnostics

The first subsegment is the most relevant to the company, so I’ll focus on that one. Through Drug Containment Solutions, Stevanato manufactures and sells primary containment solutions to the healthcare industry (the company sells billions of such products every year). These containers are called ‘primary’ because they are in direct contact with the drug and, therefore, follow stringent regulatory and cleanliness standards. It’s also worth noting that these containment solutions tend to hold primarily biologics, which, due to their sensitivity, need to be injected into the body in liquid form (from what I’ve read, if a biologic were to be ingested, the stomach would most likely kill the protein and thus drastically reduce the efficacy of the drug).

These containment solutions can come in many shapes and forms, like vials, syringes, cartridges, or ampoules. These words might sound unfamiliar to you but should automatically become more familiar after looking at the image below. The container on the left is a cartridge, the one on its right is a vial, and the one next to last on the right is an ampoule:

These primary containers can also be categorized by size and/or quality. The categorization is not precisely accurate, but they can be divided into bulk or high-value products. Bulk containment solutions are typically lower quality (you’ll understand what I mean later on) and can carry more liquid. You typically have more than one dose of the drug in a bulk vial. These are typically used in scaled manufacturing where high volumes of a given drug are being manufactured, and the drug is not as sensible/valuable. These tend to be commodity-like products, although this is probably an unfair categorization because customers would not trust unproven suppliers.

On the other hand, high-value products typically contain more valuable drugs stored in lower quantities (one dose per containment solution). These are called high-value products because Stevanato conducts certain tasks on the products on behalf of its customers, like washing and sterilization (such tasks used to be performed by the customers themselves). The goal is to offer customers a safe product they can use directly without incurring Capex (in washing and sterilization lines) and time to do so in-house. An example of such a product would be a ready-to-use vial, where a customer can simply fill it in because it has already been sterilized and visually inspected by Stevanato. The company touts these kinds of products as products in which they…

“Hold intellectual property rights or have strong proprietary know-how and that are characterized by technological and process complexity and high performance.” (Source: 20F)

There’s obviously some truth to this, but the reality is that premium, or high-value products can be described as regular products to which Stevanato has conducted a series of services so that the customer does not have to. An excellent example of a HVP for Stevanato is the Ez-Fill Platform, which is basically its ready-to-use platform. Pharma companies used to be in charge of washing, sterilizing, and filling their containers. This led to high Capex (to build the capacity to do such tasks) and long manufacturing times. Through its Ez-Fill Platform, Stevanato is now in charge of the washing and sterilization, and the pharma company can directly fill it in (Stevanato does not provide filling services):

After analyzing the company and industry for some time, it’s easy to see what’s happening here…Pharma companies have realized that they must be leaner and focused on what they do best (researching drugs), so they have decided to outsource such activities. What was previously a vertically integrated industry (i.e., pharma companies conducting most tasks) is now a specialized industry, which tends to happen when complexity increases (see the semiconductor industry). Complexity here has come in the form of biologics, which are much more complex and sensible drugs than small molecules (biologics are known as large molecules).

The primary container manufacturers have gladly taken on this increased Capex but have also taken their fair share of the value created by insourcing such tasks and launching high-value products. The unit economics between regular and high-value products are markedly different. The latter typically carry a 10x larger selling price and around double the gross margins of the former. So, yes, the Stevanatos and Wests of the world will probably be more capital-intensive going forward (although nothing crazy considering that Stevanato sees maintenance Capex at around 3% of sales), but they will most likely be higher-margin businesses. The industry has been transitioning to HVPs for several years, and this transition seems unstoppable. I will explain why in the next article when discussing the growth drivers.

So, in short, through its drug containment solutions, Stevanato manufactures containers (mainly glass) where injectable drugs (mainly biologics) are stored until they are administered to a patient. The company also plays a relevant role in this administration phase through its drug delivery devices subsegment. The company does three main things here…

Sells primary containers optimized for a customer’s drug delivery device

Manufactures its own proprietary drug-delivery devices (like pen injectors, wearables, or auto-injectors)

Manufactures drug delivery devices for its customers (contract manufacturing)

This is also an important subsegment in the company’s vertical integration journey, as there’s a trend of self-administration in the industry. The healthcare industry “loses” billions of dollars every year from people having to come to a hospital to get an injectable drug administered, so they are obviously pushing for people to be able to self-administer these in their own homes. Being active in the drug delivery space makes sense for Stevanato because it allows them to offer the entire package: the container and the method through which it’s administered.

Lastly, through in-vitro diagnostics, Stevanato manufactures consumables for In-Vitro Diagnostics. These tend to be quite complex and specialized. “In-vitro” means “in glass,” so these are consumables that Stevanato produces thanks to its expertise in glass forming.

The Engineering Segment - 19% of 2023 revenue

The company’s engineering segment is what probably makes it unique compared to peers. According to Stevanato’s management, owning this technology is a key competitive advantage:

We are the market leader in glass converting, the critical technology for manufacturing containment solutions. Owning this technology represents a key competitive advantage that is unique to Stevanato.

The engineering segment is, at heart, an industrial segment through which Stevanato manufactures equipment used throughout the fill-and-finish value chain. The company manufactures four main types of equipment:

Assembly: used to assemble drug delivery systems like pen injectors, nasal sprays, etc

Visual inspection: used to inspect the containment solutions after they have been filled in the search for contamination or breakages. Inspection is a key step in the process because identifying early signs of contamination can save a pharma company millions of dollars

Packaging and Serialization: this is more related to secondary packaging, where Stevanato’s systems also label the drug to make it traceable

Glass converting: sharing it here last, but glass converting is the first step in the value chain. It’s the technology that allows Stevanato (and its customers) to transform glass into vials, ampoules, cartridges, etc. The company has been doing this since 1971 (the foundation of Spami), and it constitutes one of its primary advantages as other companies don’t own their technology

An important thing to note here is that Stevanato is customer zero for most of these technologies, especially today when the company is insourcing tasks previously conducted by its customers. So, for example, now that the company is conducting a capacity expansion plan, most of the machines used to fill new plants are coming from the engineering division. This, together with the high demand this division saw during the pandemic, might be putting too much pressure on its capacity (more on this in other articles).

Other customers for the engineering segment (besides Stevanato itself) would be pharma companies, CDMOs, and even Stevanato’s peers/competitors. CDMO stands for ‘Contract Development and Manufacturing Organization’, and they are the companies to which pharma companies tend to outsource the production of their drugs. Large pharma companies might have the means to in-source their production, but smaller biotech companies don’t. CDMOs were born as the answer to high capital needs, just like ready-to-use primary packaging.

So, if we were to have a 360º vision of Stevanato, it would look something like this:

Stevanato can basically provide end-to-end services for its customers:

We can provide, of course, as we mentioned, the container solution, we can provide the device solution, we can provide the equipment to pull them together and to inspect them. We are really the only company in the space that can do all these three things together, and this is our big competitive advantage.

Is vertical integration really an advantage in the industry? We’ll only know the answer to this question in hindsight, but something that gives credibility to Stevanato’s strategy is the fact that other companies are playing catch-up. For example, West Pharmaceuticals is now trying to vertically integrate through some partnerships (like the one with Corning), and management has admitted that they are open to M&A to complete their portfolio. Stevanato, on the other hand, has said the exact opposite: they don’t need M&A because they are already vertically integrated.

There are also some synergies across both segments besides Stevanato being a significant customer of its engineering services. The main synergy is that, when customers purchase the Ez-Fill line, they must change the inspection system too, which is a positive for the company’s engineering segment.

Some thoughts about the stock and valuation

Stevanato is an Italian company publicly traded in the US (only) under the ticker ‘STVN.’ As discussed throughout the article, the family still owns a significant chunk of the business. This means the float is limited, so the stock tends to be quite volatile, especially with the current headwinds. As most of you know, I don’t consider volatility to be a risk, but this is just a heads-up in case you see “unusual” moves.

I’ll review the valuation in more detail in another article, but I’ll leave a glimpse here. Stevanato currently has a relatively high PE ratio of 37x (Last Twelve Months), although it’s not normalized for two main reasons…

There are non-recurring start-up costs included in the company’s earnings related to the opening of the different manufacturing plants

Margins are not normalized due to destocking and temporary headwinds in the engineering division

The forward PE ratio already does an okay job at normalizing some of these problems (Stevanato is trading at 31x forward earnings), but some of the “solutions” to such headwinds are longer-term in nature, meaning that next year’s margins are also unlikely to be normalized:

Management has guided for a return to double-digit growth post-destocking, which makes sense considering that the segments of BDS that are not suffering destocking are still growing above this rate (although masked behind the destocking).

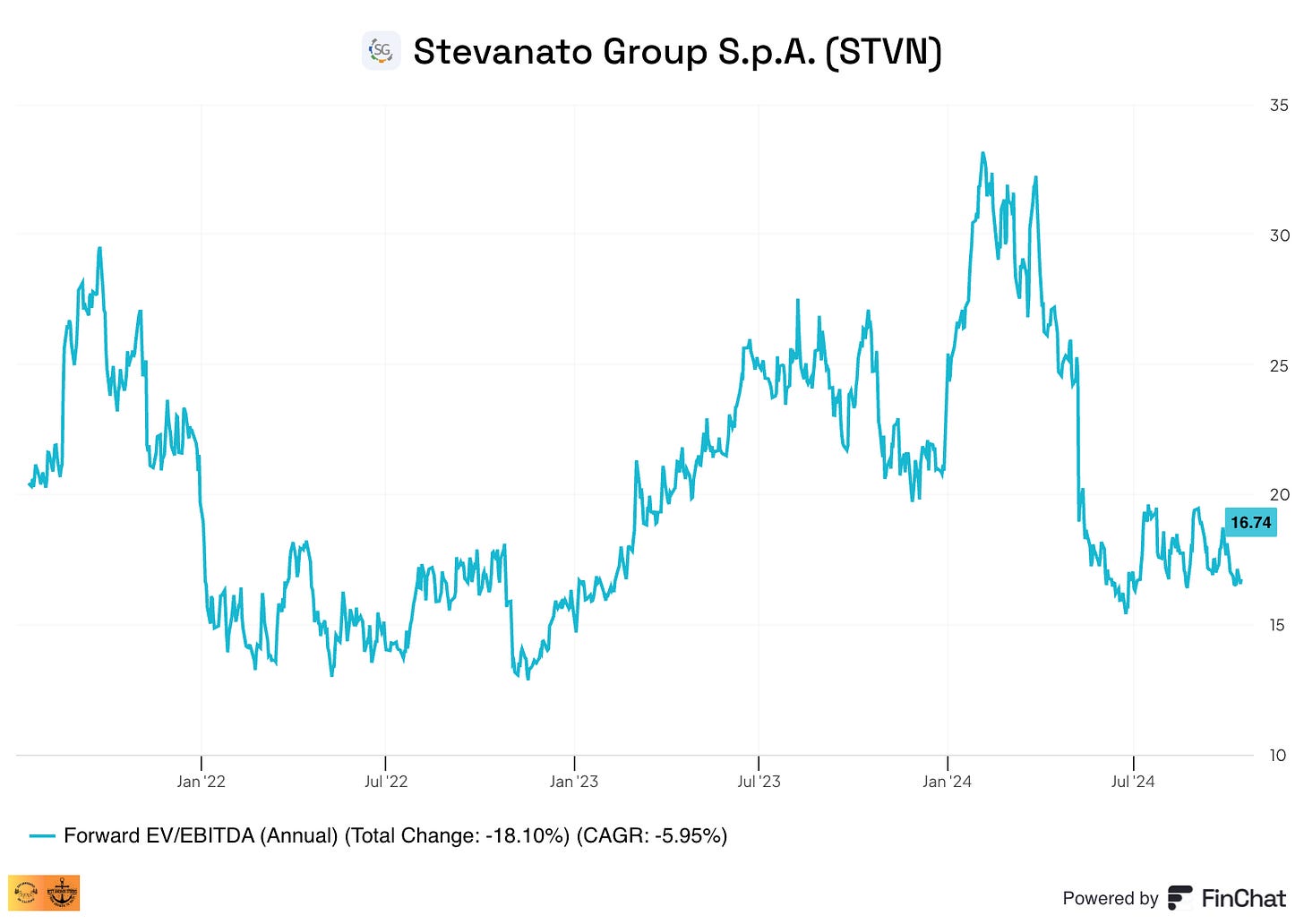

I’ll talk more about the growth drivers in the following article, but we should also consider that a good portion of this growth comes from the transition to HVP (high-value products), so it’s more replacement demand than new demand, and it’s part of multiyear agreements with customers. This HVP demand should also bring higher margins, which is why management targets a 30% adjusted EBITDA margin in 2027. Even if we adjust those numbers lower and think the company will get “only” to 28% EBITDA margins, we get around a 15% EBITDA CAGR up until 2027, with expectations of continued double-digit growth going forward. Stevanato is currently trading at a forward EV/EBITDA of 16x despite all the above headwinds and the expected growth:

If we compare it with peers (West, Schott Pharma, and Gerresheimer) on a P/S basis (I am using P/S because earnings are not normalized, and these are somewhat comparable businesses), we can see that Stevanato trades considerably cheaper than West and similar to Schott. Gerresheimer is the cheapest of the bunch, but it’s also the worst company of the group facing considerable execution problems (they got an activist recently, but that’s a topic for another article):

4.5x sales is definitely not a cheap multiple, but I believe Stevanato is a double-digit grower that can achieve above 20% operating margins in the future, meaning that operating income growth should comfortably land around the mid-teens CAGR. Of course, judging by the company’s recent performance, one would never say this is going to happen, but there are many headwinds that should dissipate in due time. Things could definitely get worse before they get better, though.

In the meantime, keep growing!

Leandro

Read part 2 here 👇🏻

You write exceptionally well man. Loved it.