A fertile ground for the individual investor

My Ideal Investment Scenario

Hi reader,

We are constantly bombarded with statistics that point out how tough beating the market is, so as an individual investor, it’s normal to ask ourselves…

How can I beat the market? What’s my edge?

It’s no exaggeration that beating the market over long periods is tough, but we can find hope in the fact that some investors have managed to do it consistently (i.e., it can be done). In this article, I don’t plan to tell you how to beat the market (first, I must find out if I can do it myself over a long period). My goal here is to share the types of investment opportunities that I believe can lead to good risk-adjusted returns.

I (unfortunately) did not implement this strategy as soon as I began investing. Investors must always be constantly evolving, and I have significantly evolved my investing strategy throughout these years. I was already amid my pivot to the type of opportunities I’ll explain in this article when I came across this Jerome Dodson interview (courtesy of my friend John Rotonti). Jerome Dodson founded Parnassus Investments and shared in the interview the opportunities he found most appealing as an investor:

Many of our biggest winners have been companies that operate in cyclical industries with secular growth drivers. When their business cycle turns down, investors become overly pessimistic and extrapolate the current negative conditions. They forget the cycle will eventually turn, throw in the towel on the secular growth drivers, and engage in panic selling, pushing the stock to bargain-basement levels. But eventually the cycle turns, and the stock soars higher. It's difficult to have the courage to buy when everyone else is selling, and this has been an important part of our success.

This extract from the interview ended up shaping me as an investor far more than I had ever imagined.

My ideal investment scenario

Companies must meet certain characteristics to fit my ideal investment scenario. These characteristics are not rocket science and can be “easily” spotted by anyone. I’ll first discuss them and then explain why it’s tough for most of the investment industry to exploit these opportunities despite them “hiding in plain sight.”

Characteristic #1: Cyclical but secular

I despised cyclicality in my early days as an investor. This “fear of cyclicality” led me to focus my search on companies with linear fundamentals, which can also constitute attractive investment opportunities (I hold a fair share of them) but tend to come with a “downside”: extremely linear and stable businesses rarely suffer extreme price dislocations outside of broad market sell-offs. This doesn’t mean that they are never undervalued (a good portion of these businesses manage to beat the market over long periods) but that it’s rare for them to become a fat pitch (again, unless the broad market is selling off).

We can find two types of businesses in the cyclicality arena. First, those that are continuously cyclical, meaning that they don’t tend to grow above GDP through the cycles. Many (not all) commodity businesses fit this bill. The second group comprises cyclical companies that manage to grow above GDP growth rates through the cycle (this might be either in revenue or earnings). It's this second group that I am interested in. The difference is subtle but quite relevant as one must time the cycle to perfection in the first group, whereas this is not a requirement in the second group as you’ll enjoy growth regardless of the cycle’s timing.

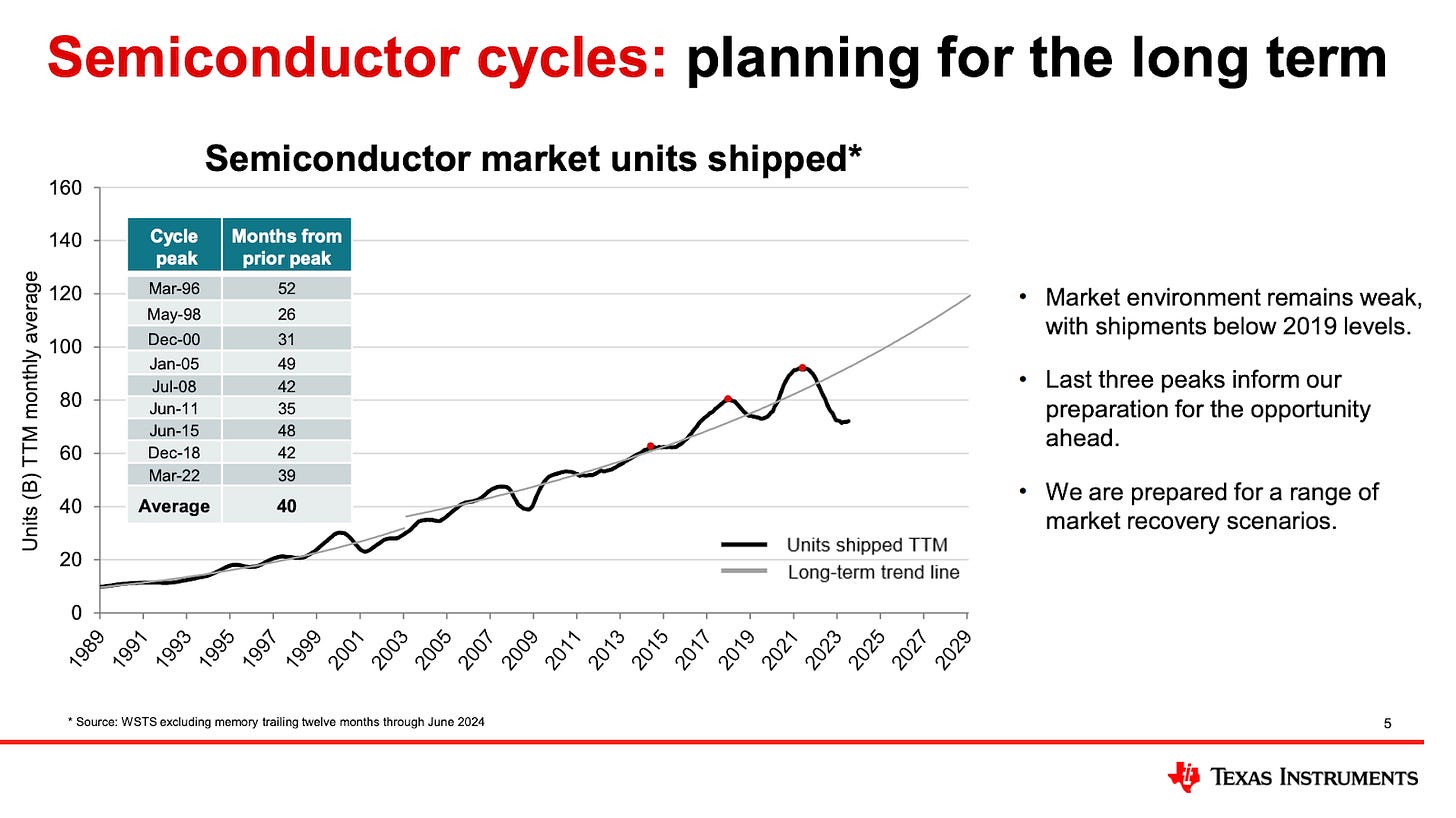

The semiconductor industry is a perfect example of an industry that belongs to the second group. It’s a cyclical industry due to a supply/demand imbalance created by long supply lead times coupled with fast demand changes (which means that supply might come online when demand has already shifted). Despite these historical cycles, the long-term trend has remained unstoppable: up and to the right. I believe this chart from Texas Instruments’ recent capital management update illustrates the point well:

Secularity within cyclicality tends to apply to entire industries, but it can also apply only to one or a few companies in a given industry. You’ll understand why this characteristic is important later on.

Characteristic #2: A strong balance sheet and cash-profitable through the downcycle

In an ideal scenario, a company experiencing a temporary downturn has a strong balance sheet and generates substantial cash in the worst part of the cycle. Both of these traits have very positive implications. The first and most obvious one is that the company can weather the downturn without having to significantly cut its investments or restructure its debt. Survival is a requirement for generating good returns over the long term.

The second positive implication is that the cash generation capacity allows the company to magnify the inevitable upcycle by retiring a significant number of shares at attractive prices. In short, it enables management to be countercyclical when it adds the most value.

Characteristic #3: An improving business through the cycle

Good businesses focus on continuous improvement, and these temporary downcycles are the ideal scenario for accelerating such improvements. The goal is to find a company that will not only recover from the downcycle but in which you can confidently claim that it’ll be a better business in the next peak. In some cases, this happens naturally as weaker players are filtered when times get rough. This allows the strongest companies to emerge with a stronger competitive position (i.e., the market consolidates).

In other cases, improvements tend to result from actions targeted explicitly by the company. In most cases, it’s a bit of both. When things are going well, there’s almost always no need to reduce the fat in the business, but this tends to change when things get rough, even if the business continues to be widely profitable.

So, if I were to summarize these three characteristics in a sentence, it would look something like this:

My ideal investment scenario is one where the company/industry is suffering a temporary downcycle but in which the business is striving to improve through it and the management team has the funds to be countercyclical.

As you can see, it's not rocket science.

The source of the opportunity

The above sounds nice, but why is there an opportunity if these three characteristics are apparent to everyone? Shouldn’t investors flock to these types of opportunities, thereby making them less appealing? My hunch is that many investors sometimes tend to disregard these companies for two main reasons that have little to do with any of the characteristics I discussed above and which are intrinsically related: opportunity cost and the industry’s incentive structure.

I’ve talked about the investment industry’s incentive structure several times in the past and why I believe it constitutes an advantage for individual investors. The bottom line is that most funds’ incremental profits come from increasing AUM (Assets Under Management), so as one would’ve rightly imagined, they strive to do just that. As LPs (Limited Partners) might jump ship if a fund suffers an “unjustifiable” underperforming year, what do most funds do to retain/increase AUM? Correct, they try to outperform over any period or at least do something similar to their benchmark.

Note that redemptions not only reduce asset management fees but can also have implications for the fund's long-term performance as PMs (Portfolio Managers) might be “forced” to sell undervalued companies to service these redemptions. This quest to outperform every single year results in two common behaviors in the investment industry:

Index hugging: you can’t “unjustifiably underperform” if your portfolio mirrors the benchmark you are being measured against.

Avoidance of opportunity-cost-type scenarios

The first one is straightforward, so let’s focus on the second. For many fund managers, finding a good investment opportunity is not enough; they must find it at the right time. Even if they believe stock “A” is a fine investment over a 5-year horizon, they will have a tough time buying it if there’s no end in sight for the current underperformance (i.e., they need a catalyst). Waiting for a catalyst seems like a fine strategy, with the only caveat that it tends to be almost impossible to forecast accurately; once the catalyst is evident, the stock price has already moved.

The period during which a stock remains somewhat flat while waiting for an inflection results in significant opportunity cost. The money locked in there can potentially lead to underperformance. A flat stock price contributes little to returns, and that money could have been better invested elsewhere. As most fund managers can’t afford underperformance (even in the short term), they tend to shy away from opportunities where there’s no apparent catalyst.

Interestingly, many individual investors fall into the same trap despite their incentives being markedly different from those of professional investors. Individual investors must get the investment thesis right, but there is no externally imposed pressure to get the timing right (there isn’t one either for professional managers strictly speaking, but we know that incentives rule the world). But why do many individual investors self-impose these limits then? I don’t have the answer to this question, but a reasonable explanation might be linked to ego: humans want to be correct at the right time. The current trends in social media have also made us crave instant gratification, which can act like a disease for long-term investment returns.

An individual investor can take advantage of the inherent limitations of the financial industry and purchase these types of opportunities when very few are willing to hold them. Also note that if characteristic #2 holds and the management team is reinvesting countercyclically, it’s in the investor’s best interest that the situation stays as-is for longer (at least in terms of the stock price), as it will magnify the upside coming out of the cycle. This advantage that allows individual investors to shrug off cyclicality (so long there’s reasonable confidence that there’s secularity) can be encompassed in two words: permanent capital.

A practical example

Let’s take a look at a practical example. One company that complies with the three characteristics discussed above is Deere (DE). I explained why in detail in the (free) deep dive, but let’s summarize it here.

Characteristic #1: Cyclical but secular

Deere is currently experiencing a downturn after the agriculture industry peaked in 2023. 2024 was the first year of this downturn, and 2025 is also expected to be a down year.

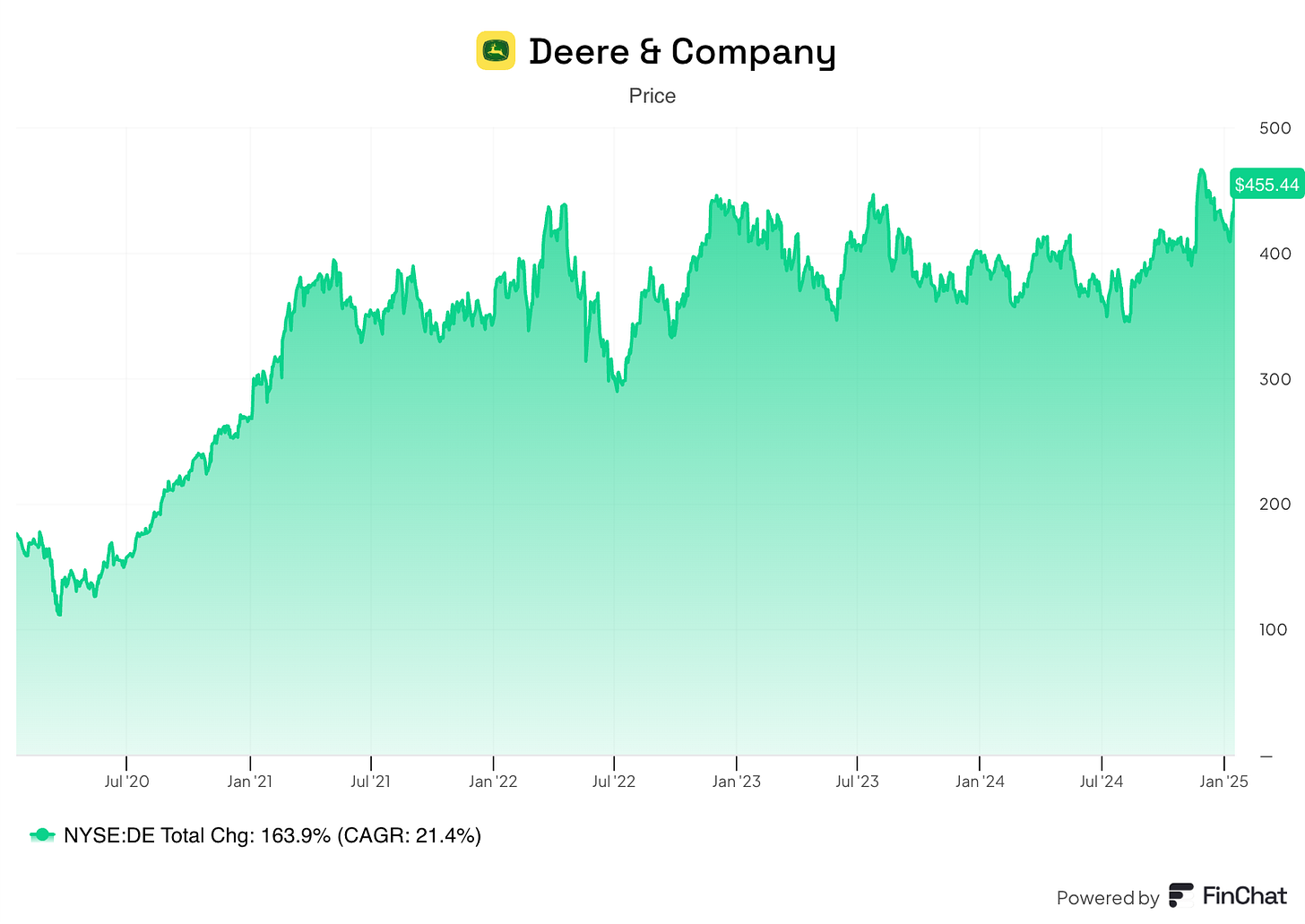

Looking at the stock price, we can see that the market is sending a clear message to investors: the stock is dead money until there’s visibility into the new cycle. Deere’s stock has just risen 9% over the past four years (against the S&P 500's 49% return):

The agriculture industry has historically been cyclical, but equipment companies in general (and Deere in particular) have grown through the cycles thanks to several secular drivers, such as…

The need to feed a growing population with less available space to crop (i.e., the need to increase productivity per acre through more powerful equipment and technology)

Labor supply problems which increased the reliance on equipment and automation

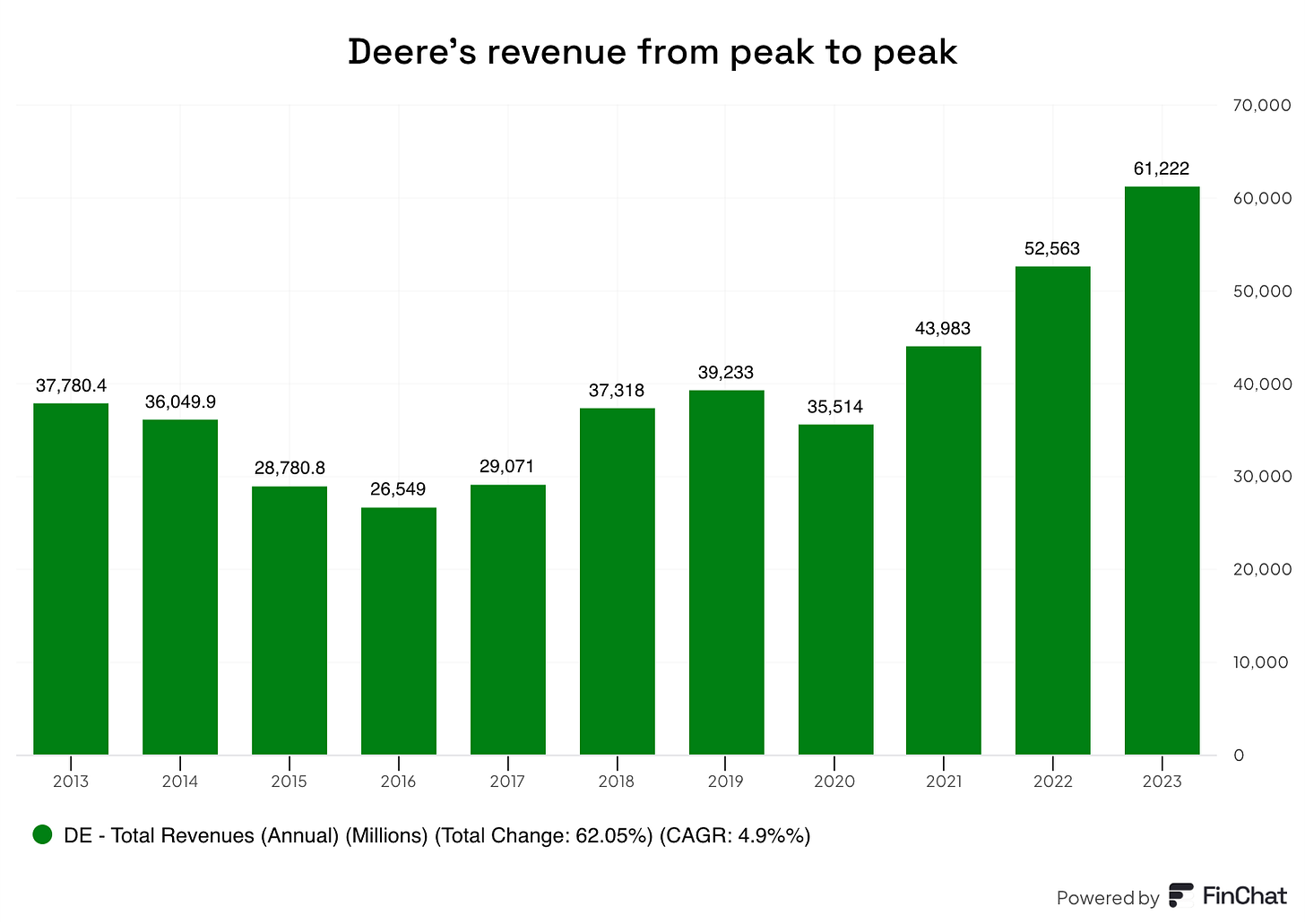

These two growth drivers drive the need for more equipment and more automation, the latter of which is accretive to Deere’s margins. If we look at Deere’s financials, we can see that there has been above-GDP revenue growth through the cycle (5% CAGR), which was more amplified in the earnings line (operating profit grew at a 9% CAGR from peak to peak):

So, it seems clear that Deere is a company that grows through the cycles.

Characteristic #2: Cash-profitable through the downcycle

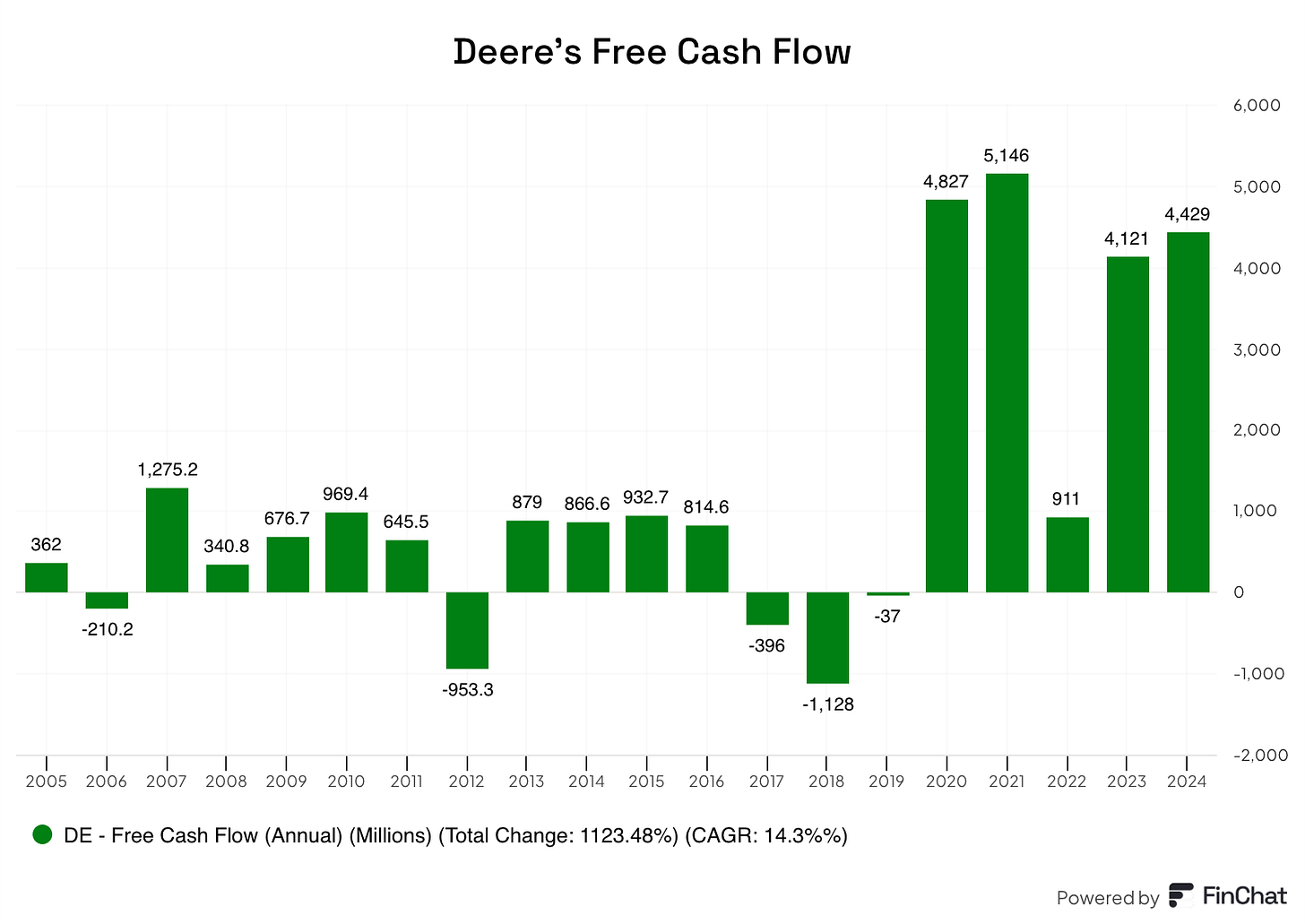

This is a pretty straightforward characteristic to analyze. Although Deere’s cash flow is somewhat volatile due to working capital movements, the company seems to generate good amounts of cash through the downcycles. The 2013 downcycle lasted from 2013 to 2017 and Deere generated a cumulative Free Cash Flow of $2.2 billion over these years.

Cash flow conversion has also improved markedly thanks to better working capital management and increased reliance on software and repair revenue. Despite 2024 being a down year for Deere, the company managed to generate $4.4 billion in Free Cash Flow and expects to generate around $3.4 billion in Free Cash Flow from Equipment operations in 2025 despite arguing that sales will end up below 80% of mid-cycle levels:

Something worth noting is that the cash flows of many industrial companies tend to be countercyclical. The reason lies in inventories. During an upcycle, these businesses run with high inventory to meet demand. This increased inventory ties cash into working capital. When a downcycle comes, these companies reduce inventory, which frees working capital and improves cash flows. Deere significantly reduced inventory in 2024 to adapt to the demand environment, which has allowed its cash flows to be more resilient when it matters most.

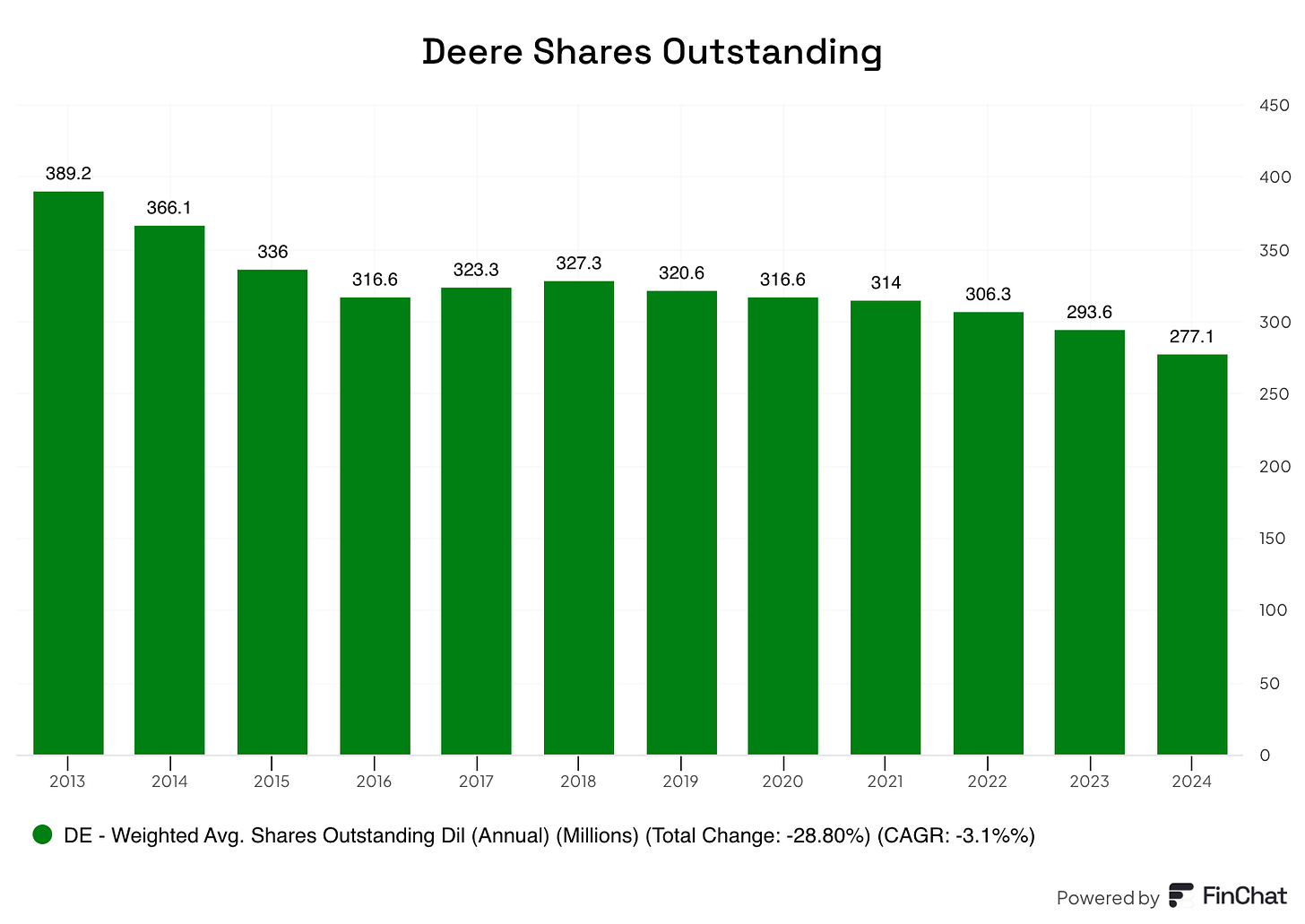

Thanks to this cash generation capacity, Deere can invest countercyclically, both in the business (through R&D and Capex) and in stock buybacks. The management team leans quite heavily on buybacks even during tough times, which has resulted in a 29% decrease in shares outstanding over the last 10 years and 14% over the last 5:

This led to strong growth in Free Cash Flow per share once the cycle recovered, which, combined with a relatively muted stock price through the downcycle ended up resulting in strong returns for patient shareholders: Deere has compounded at a 15% clip since peaking in 2011 in anticipation of the next downcycle. If an investor had waited for the actual peak in the fundamentals to invest, their CAGR would’ve been closer to 19%. Deere is behaving no differently today; the stock peaked in anticipation of a peak in the fundamentals and has remained flat since, waiting for a new upcycle.

Characteristic #3: Improving business model through the cycle

This is something that I discuss at length in the deep dive, so I will be brief here. Deere is becoming a much more profitable company through the cycles, aided by better execution and the increasing prevalence of technology (which is margin accretive). Deere’s CFO succinctly encompassed the company’s through-the-cycle improvement in the last earnings call:

“It is important to emphasize that our implied guidance of around $19 EPS is at sub-trough levels, with expected sales for fiscal 2025 below 80% of mid-cycle.”

“Our margins in 2024 exceeded 18%, reflecting nearly 700 bps of improvement from 2020, which was the last time we were at this point in the cycle.”

“Our earnings per share and cash returned to shareholders not only surpassed historical mid-cycle levels, but also historical peaks. We expect to deliver higher margins at trough than we did during the previous peak in 2013.”

I am pretty sure Deere will be a better company at the next peak of the cycle.

So, in short, Deere is a company that’s cyclical but secular, can deploy cash counter-cyclically, and is improving through the cycle. The stock has been flat for almost 4 years as many await the next cycle, but we have seen that even buying the stock before it went flat during the last cycle delivered pretty good returns for shareholders.

The use of LEAPS to reduce the opportunity cost

As you might have rightly imagined, the downside in these investment scenarios (and the reason why stocks tend to tread water) is the prevalence of opportunity cost more than the risk of a permanent loss of capital. This characteristic potentially makes it a fertile ground for the use of LEAPS.

LEAPS stands for Long-Term Equity Anticipation Securities and refers to stock options with expiration dates longer than one year. The fertile ground for these options is one where you are reasonably confident that the downside is limited and that the stock price will be higher several years down the road.

LEAPS have several advantages in these types of situations…

They allow an investor to gain the same notional exposure despite committing less capital upfront

They allow an investor to magnify their returns, which might compensate for the “higher opportunity cost” present in these types of situations

Using LEAPS is something I have never done but am considering, especially as my portfolio pivots to these types of opportunities. One needs to be aware of a couple of things before getting comfortable with LEAPS. Three things come to mind: one needs to be fairly confident that the scenario will play out as expected, that the downside is limited, and that the option is not heavily mispriced. As LEAPS are more long-term than the more prevalent options, their prices are highly sensitive to market volatility and interest rates, both of which are unknown. The fact that LEAPS pricing is subject to these unknowns means it’s not enough to get the future price right to fully benefit from them.

One of my objectives this year is to become more knowledgeable about these types of instruments and maybe apply them in the future as my investment universe pivots toward these types of opportunities. Options tend to have a negative connotation (I am guilty of this, too), but they can be great instruments when used correctly.

It was interesting to discover that around 45% of my portfolio is exposed to this type of investment scenario. Deere is a great example of this, and another good example is Keysight (KEYS), a company for which I published a deep dive not long ago.

What’s interesting is that the pandemic might have created more of these types of opportunities than usual. Many companies suffered from a boom and bust during this period and are now experiencing the bust. Few investors are willing to hold on to these until there are green shoots on the horizon, and Stevanato Group (a free deep dive is available) is one such example.

In the meantime, keep growing!

Thank you for another mental model to add to the arsenal!

Thanks for this comprehensive post. Great concept, not shying away from cyclical and instead seeing it as an opportunity. Really appreciated this one, thanks.