4 Topics That Define My Investment Philosophy

Hi reader,

One of the things any investor should do is read, and when I say read…I mean read a lot. I will not be the one who outlines the benefits of reading (these have already been well documented), but I believe this activity can have tremendous benefits for any investor’s process. Many investors view reading simply as a way to source investment ideas. While idea sourcing is definitely one of the benefits, I’d say the primary benefit is that it helps us develop critical thinking while defining our investment philosophy along the way. Contrary to what the investment industry wants to make individual investors believe, one doesn’t need a course or a degree to invest well; all they need is time and curiosity, and probably more of the latter than the former.

You might be thinking…

Where is he going with all this?

Fair point. This article is kind of a special one because it’s the first time I've done something like this. I recently read a book that has entered my top five all-time favorite investing books. The book is called “What I Learned About Investing from Darwin.”

I think the title is already quite descriptive, but maybe this quote from the book should help you understand further what it’s about:

Almost every topic I studied in evolutionary biology has parallels to investing in general.

Some people will agree that it’s a good book, others won’t. This opinion divergence is perfectly fine (and should be the norm) because reading is a very personal topic. I have read books that were recommended to me that I had to put down after several chapters, which doesn’t mean the book was bad but rather that it didn’t fit me.

So, why did I enjoy this book so much? The main reason is that I felt my investing philosophy was reflected in it. From there, I thought it would be a great idea to write an article discussing four topics (+1 additional) that I believe are crucial to my investing philosophy using examples from the book.

But let me provide some context first…

Who is Pulak Prasad, and what is Nalanda Capital?

As you might have deduced from the title of this section, the book was written by Pulak Prasad:

Pulak is an Indian citizen who started his professional career working for McKinsey. After several years as a consultant, he started his own fund, Nalanda Capital, in 2007. The fund's performance has been outstanding, compounding at a CAGR of 20.3% (net of fees) from 2007 until the book's publication in 2023 (roughly 15 years). This means that if one had invested in Nalanda Capital at its inception, they would have around 16x their money today. Pulak might not be as high-profile as other investors but his performance is up there with the all-time greats.

The most interesting thing is that Nalanda Capital has achieved this outstanding return by focusing exclusively on Indian equities. Pulak is a living testament to what “staying within your circle of competence” stands for.

As you are reading this article in the Best Anchor Stocks blog and you somewhat know what my investing philosophy is, you might have imagined what kind of investor Pulak is. He buys and holds high-quality businesses for the long term, patiently waiting for opportunities as such companies seldom come cheap. And when I say he waits, I really mean it. Since the fund's inception in 2007, Pulak has only deployed significant amounts of capital a few times.

But, what is a quality company? This is always a subjective question, but I think it’s best if you hear it from Pulak himself:

For us, the critical character traits of a high-quality business are stellar operating and financial track records, a stable industry, a high governance standard, a defensible moat, increasing market share, and low business and financial risk.

As discussed at the beginning of the article, I thought it would be a good idea to write an article discussing four topics that shaped my investing philosophy. The book provides an excellent framework for thinking about such topics, so I will use its quotes to clarify the point where necessary. I have already written about some of these topics, so I’ll also share those articles here.

The fifth section is not a topic per se but rather an explanation of why the individual investor can beat the average professional investor. Without further ado, let’s go with the first topic.

1. The art of saying “no”

The first topic I’d like to discuss is the art of saying “no,” not because I have recently written an article on it but because I believe an investor’s ability to say “no” is probably one of their most crucial competitive advantages. Pulak agrees:

I will argue that learning the skill of not investing is harder and more important than learning how to invest.

But, why is this the case? The answer lies in the numbers. There’s no denying that successful investors have to be selective. Say an investor decides to build a portfolio of 15 or 20 businesses. Where would he have to choose these businesses from? The universe of publicly traded companies, and this universe is…pretty large, put mildly. As of Q1 2022 there were approximately 58,000 listed companies worldwide. This basically means that an investor who wants to build a 15-20 business portfolio is claiming they want to hold around 0.02% of all publicly listed companies.

Such a small percentage simply demonstrates that investors should be willing to be highly selective and disciplined in selecting their investments if they wish to own the best of the best. Finding the best of the best among 58,000 listed companies (granted, you probably don’t have access to the entire universe, but still) is like finding a needle in a haystack and will require a lot of discipline. The reason is that the first 15 or 20 companies we analyze are unlikely to be the highest-quality companies in the set. I mean, I am no statistician, but the probability of that happening is probably close to zero. (Small note here: there are obviously “quick” ways to make this universe smaller, but even then the available companies will probably be quite significant.)

I believe that saying “no” seems straightforward and logical, but I have found over the years that 90%+ of investors are “programmed” to say “yes.” I must say I don’t know the reason why, but I can intuitively think about one: the sunk cost fallacy. Maybe this is not the appropriate term, but I feel it does a pretty good job naming what I am about to describe. For me, the sunk cost fallacy presents itself when investors do deep research (I must admit that not many do) and make an irrational decision to avoid thinking they “worked in vain.” Simply put, if investors study a company for 20 hours, they might feel better about themselves if all that work leads to a purchase (action) rather than if it leads to inaction.

As discussed in the article I linked above, investors should not consider research a sunk cost but rather an investment because any type of analysis should help an investor improve their pattern recognition ability. Nalanda Capital is geared precisely to the opposite and is probably one of the main reasons why the fund has historically avoided capital losses:

Our starting hypothesis with every business is that we don’t want to own it.

2. Debt, durability, and long-term investing

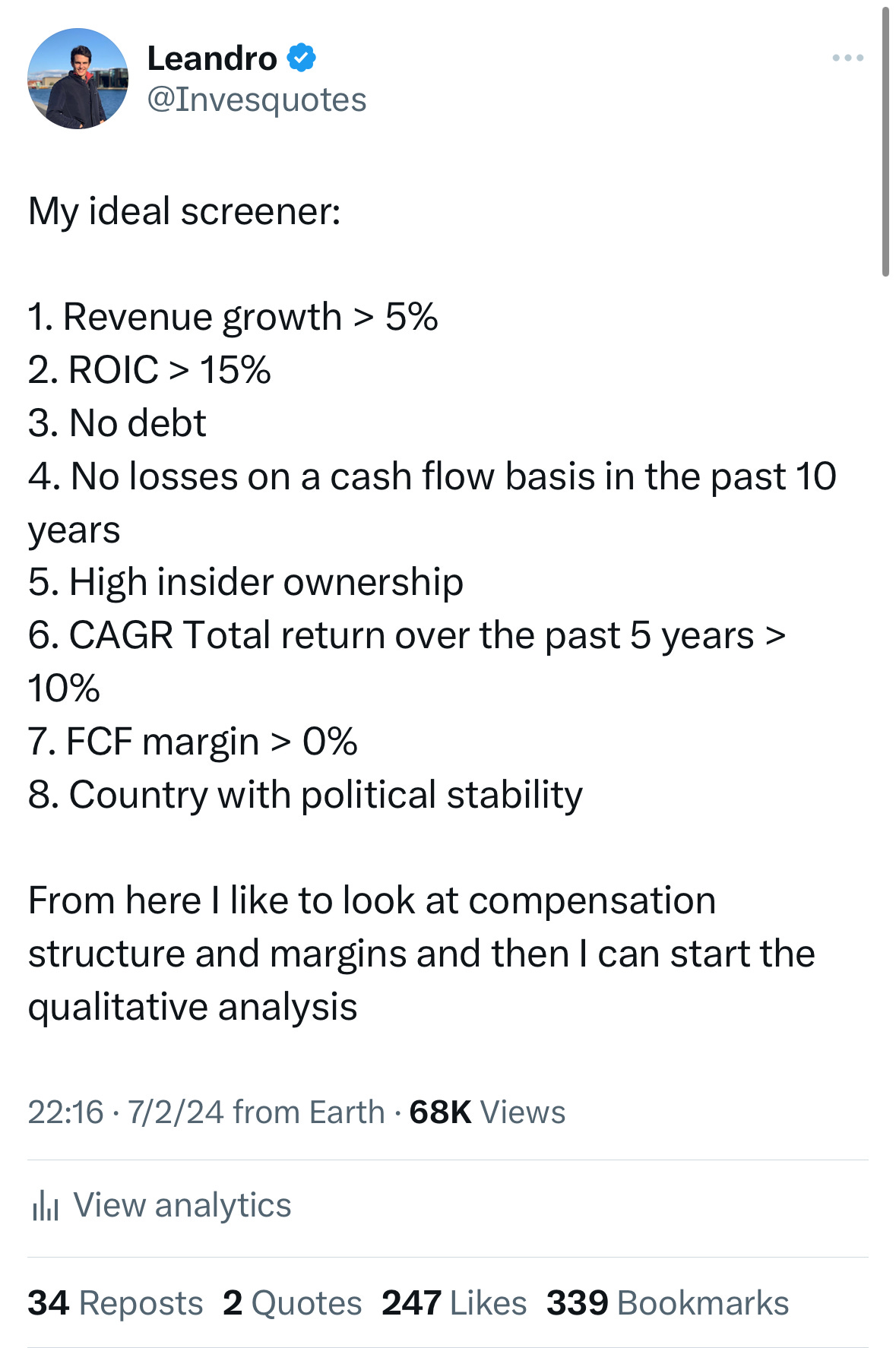

The three topics you read in this section’s title are all intrinsically related, and I’ll try to explain why. Several weeks ago, I shared some of the filters that I typically use to screen and got quite a bit of pushback on one of them:

The criterion that received the most pushback was “no debt.” Many claimed that debt is good because it can help juice returns, and pretty much any balance sheet of a good company can sustain a bit of debt. While I agree with this to an extent, if one is extremely focused on durability, I don’t think the risk-return tradeoff of “juicing returns” is worth it. As Pulak succinctly writes…

There is no point in improving return on equity by a few percentage points if it compromises long-term survival.

I remember reading something similar in David Giroux’s book ‘Capital Allocation.’ It went along the following lines, although I might be changing some words…

The present value of a company that does not pay dividends, compounds at 10% over 20 years, and then goes bankrupt is zero.

This said, low debt is not just about long-term survival; it’s also essential for strategic flexibility:

Debt diminishes strategic flexibility and hence long-term value creation. For a permanent owner like Nalanda, any constraint that prevents a business from taking calculated strategic bets is undesirable.

Shareholders' desire to carry more, less, or no debt seems intrinsically linked to their investment horizons. The longer the investment horizon, the less debt one should be willing to carry. Long-term investors care dearly about terminal value and durability, which is much more protected in businesses carrying little debt. The future is unknowable, but it’s definitely much tougher to go bust being in a net cash position.

Looking for companies with very low or no debt reduces the universe of potential targets quite significantly, but this should not be a problem. Recall that an investor only needs to purchase 0.02% of the market to build a pretty diversified portfolio. I am pretty sure that a sufficient number of high-quality companies comply with this criterion. In fact, I’d go as far as to say that the percentage of high-quality companies with very low levels of debt is much higher than that of low-quality companies with low levels of debt. Why? I don’t know exactly, but I feel that high-quality companies tend to be focused on the long term, and a high debt position is not a good fit for such a vision.

I’d like to end this section with now one of my preferred quotes of all time:

A strong balance sheet is not the one that maximizes debt to minimize the cost of capital but the one that minimizes debt to maximize the safety of capital.

I believe this trait shows itself in the Best Anchor Stock portfolio.

The equally-weighted leverage ratio (net debt/EBITDA) of the portfolio is currently 0.48. This is pretty low, more so considering the resilience of most companies in the portfolio.

There are 6 companies enjoying a net cash position.

4 companies carry no financial debt whatsoever.

The premium subscription gives you access to all the content in Best Anchor Stocks, which includes…

All the deep dives

Recurring articles

Access to my real-time portfolio and transactions

Occasional webinars on various topics

A community of like-minded investors

A subscription the Premium + also gets you a quarterly Q&A with me to discuss anything you’d like.

If you want to know the type of content I share at Best Anchor Stocks you can read the Deere deep dive I uploaded a few weeks ago for free…

…or you can also read any of the other many free articles I have shared, just like this one!

You can also read the testimonials that existing subscribers have left. If you are a passionate and curious investor wanting to learn about high-quality companies, don’t hesitate to join Best Anchor Stocks!

3. The past as a proxy for the future

I like this topic, and I have already written about it several times. The article I wrote on this topic is ‘The Lindy Effect And Antifragility: Why The Past Matters.’ Many investors tend to disregard the past when making investment decisions, but I believe the analysis of the past should play a critical role in any research process. The main reason is that it’s knowable, unlike the future.

Pulak shares a similar philosophy at Nalanda Capital:

As long-term investors, we have dissociated ourselves from the “what will happen” obsessions and replaced it with “what has actually happened?”

Relying on history is a time-tested way to keep the odds firmly in our favor.

Focusing on the past has several implications. The first one is that you’ll obviously disregard turnarounds due to their lousy past:

The corporate world is brutally competitive. Even the best companies have to run hard to stay in the same place. How could the probability of success at a troubled company be anything but minuscule?

Stasis is the default. Great businesses stay great. Bad businesses remain bad.

While reading the book, I identified with the concept of stasis. According to Pulak, the default in the world is “stasis," so “no change” rather than change. As you might know, this is not how many investors view the “default.” Many argue that companies are constantly mean-reverting and that everything changes extremely fast. My feeling is that things don’t change as fast as many think they do, but rather that change is much more sellable than stasis. This “sellability” (I know this might not be a word, but you get me) incentivizes the media to show that everything constantly changes. Do you imagine watching the financial news to hear that nothing has changed? Me neither. Show me the incentive, and I’ll show you the outcome.

The second implication of focusing on the past is that it allows you to ignore forecasts completely. You’d do yourself a favor by doing so because the track record of forecasters is abysmal…

Since the year 2000, the median Wall Street forecast has never predicted a stock market decline in the next year.

0 forecasted stock market declines since 2000, but we’ve had 5 years with negative returns in the S&P 500 over that period. I don’t blame the forecasters, though. The probability of a down year over that period has been 21% (5 divided by 23), so the most likely outcome is that the market is up next year; it’s simply the correct probabilistic bet. This, however, doesn’t mean that they know what they are doing.

Our forecasting ability is also low when it comes to individual companies. Pulak discusses the concept of multiplicative probability. To get EPS right, the forecasters must accurately forecast every line of the income statement, so the probability of success is extremely low:

Whichever way you evaluate the probability of guessing the next year’s financials correctly, it is probably worse than guessing head or tails after tossing a coin.

The terrible forecasting ability also applies to management. I have never been fond of management giving out guidance because its only objective is to please the investment industry rather than providing tangible benefits to shareholders. Pulak agrees and goes further…

If the company’s management can’t forecast correctly, how can investors do so? They can’t. More importantly, they shouldn’t try.

Guidance can become a more severe problem when it’s included in the incentive system. If a management team is incentivized to meet financial guidance, then they might lose their long-term focus. Conversely, a good incentive system can bring excellent outcomes, but what’s good? An incentive system that focuses on making the company better, not bigger.

Great businesses try neither to maximize operating profit nor minimize capital deployed; they try to earn the maximum operating profit per unit of capital deployed.

To judge if a business has a good track record of becoming better (rather than bigger), we must look at its historical return metrics. These act as a great filter because they tend to encompass three key management traits and one key business trait:

Discipline (Management)

Consistency (Management)

Good capital allocation (Management)

A competitive advantage (Business)

A sustained high ROCE is a good starting point to conclude that the company may have some kind of competitive advantage.

One would think that every investor would focus on such a critical metric, but the reality is different. Just focusing on the history of such an important metric and trying to understand how the company achieved it and what makes it sustainable puts you ahead of the pack:

Starting with a good understanding of the historical ROCE of a business will ensure you are miles ahead of your competition.

The bottom line is that investors should never disregard the past because it can teach them a lot about the future, and best of all, it doesn’t require any forecasting. To believe that the past is a good proxy of the future, you must be a believer in the concept of stasis (which I am).

I also believe this trait presents itself in the Best Anchor Stock portfolio, which is made up of mostly proven winners:

The average age of the portfolio companies is 78 years, with four companies that are more than 130 years old.

All the companies are profitable (22% average net income margin) and enjoy good returns (average ROIC of 15%).

(If you want to have access to the portfolio don’t hesitate to join Best Anchor Stocks, there’s a 2-week free trial.)

4. Cultivating a bias toward never selling…with a twist

Nalanda Capital has a relatively uncommon view regarding selling: they’ll never sell due to valuation reasons. Why? The main reason stems from the asymmetric nature of stock investing. This asymmetry is created by stocks enjoying unlimited upside but capped downside at 100%. If you focus on high-quality companies bought at fair prices, you are, in essence, already protecting a good deal of your downside. This means that the real risk is selling too soon:

We prefer to run the risk of selling late and losing some capital than selling early and forgoing substantial gain.

Just a side note here…I have never shorted, and never will, for the reason I discussed above: the asymmetric nature of stocks. I believe this asymmetry is a gift for any investor, and by shorting, one is effectively turning this gift into a poisonous pill: when shorting, your downside will be uncapped while your upside will be capped. I don’t blame those who do short, but it’s not for me. There are ample opportunities to make money on the long side, so I don’t think there’s a need to try to make money on the downside.

The second reason selling for valuation reasons might not be the best idea is opportunity cost. If you sell an outstanding business because your expected forward IRR is lower, you must find a better opportunity to deploy that capital. This does not seem like a problem, but if you are very stringent with your quality criteria, these capital deployment opportunities will not be abundant:

The opportunity to own an outstanding business comes along very rarely, and if we have won this lottery, why should we kill the goose laying the golden eggs?

The third reason selling for valuation reasons might not make sense is obviously taxes and commissions. Individual investors must pay taxes on capital gains every time they sell a winning position. In some countries, funds do not have to pay taxes when they trade, but they do have to pay transaction fees, which inevitably eat into their return.

The fourth and last reason why Nalanda Capital has chosen not to sell for valuation reasons is that the wealthiest people in the world built their fortunes by never selling:

Everyone sees immeasurable wealth being created by people who never sell, but they think and act as if it is selling that creates wealth.

I know what you are thinking…doesn’t this carry a bit of survivorship bias? I am pretty sure hundreds of people went bankrupt because they did not sell at the right time. While this is true, those cases also had one of the following characteristics in common or both:

They were levered

They were not great businesses

If something looks expensive and the business is doing great, the best decision might be not to sell. Even though Pulak’s view can be considered somewhat “extreme,” I strongly agree with him. My situation is also a bit different because I find it challenging to restart a position I have sold in the past (don’t ask me why; that’s just how I am).

This trait is obviously not present in the portfolio per se but through my actions. Since the inception of the Best Anchor Stock portfolio I have purchased 15 companies. The only thing I have done regarding selling is trimm one of the companies (two times I believe) as I thought the thesis had somewhat changed, but I have not sold fully any of the 15 positions. Not because I blindly believe in "never sell," but because I don't believe the investment thesis of these companies has changed materially over this period.

5. Why can individual investors do it?

The key question for investors has always been:

If it’s so easy, why do so many underperform?

It’s a fair question that I have tried answering before, but let’s try to answer it with Nalanda Capital’s help. Your main advantage as an individual investor is that you can choose what to focus on because your career or salary does not depend on specific metrics. Many professional investors claim they are long-term oriented, but most end up succumbing to the short term for several reasons…

Incentives and career advancement: the investment industry is very competitive in AUM and career paths. It’s the short term that tends to have a more significant impact on both variables. Some professional investors have managed to educate their investor base to remain long-term oriented, but it’s not the norm.

Pulak does not talk about this directly but does talk about it indirectly:

Another reason fund managers underperform is that funds don’t like to underperform the market.

Human nature: losing money is tough, even on paper. It’s normal to get emotional during downturns and follow the consensus, but the fact that it’s normal does not make it the right choice.

…

This short-term orientation ends up leading to completely diverging focus areas. If you are worried about what will happen next year, focusing on macro is normal. If, conversely, you care about what happens over the next 10 years, then it’s normal to focus on durability and the past:

If you are keen to know the company’s revenue growth over the past 5 years, the long-term historical trend of margins, or how ROCE and free cash flow have fluctuated over a decade, you are on your own.

Another negative consequence of focusing on the short term is that differentiating the signal from the noise becomes much tougher. It’s related to the concept of stasis. There seems to be a lot going on each week, but the truth is that the world remains relatively stagnant, and disruptive changes take time to play out:

The daily, weekly, monthly and quarterly rate of change in exceptional businesses appears much greater than the rate of change measured over years and decades.

Some will claim they do look forward 10 years, but most of the time, they focus on finding the “next Amazon” or “next Tesla” rather than looking at the past to understand the future:

I believe a crucial reason for the continued underperformance of fund managers is their focus on future rewards while ignoring the treasures of the past.

The most interesting thing is that investors continue to be short-term oriented despite strong proof that this is not the best strategy to compound capital. Every investor can get a book and read that it pays to be patient, but seldom do it. Why? Probably because it takes a lot of patience. I like how Pulak describes it:

This property of compounding - that its impact seemingly remains hidden for a long time - wreaks havoc on the performance of investors because most sell too soon. The bigger mystery of compounding is not that it leads to a large number but that it doesn’t do so for a long time.

Many individual investors think they are competing against bright minds. This is evidently true, but it’s irrelevant because the most important trait to compound capital is patience, and there’s no proof that intelligence and patience are intrinsically linked. If anything, I’d say they can be mutually exclusive!

Conclusion

I hope this article has helped shed some light on my investing philosophy and other topics. I thought it would be a great idea to use Pulak Prasad’s book to write down my thoughts, as it has been a long time since I identified with a book to this extent. Regardless of whether you agree with the topics discussed above or not, I think you will agree with the following quote:

The failure of most investors does not lie in pursuing a wrong model but in failing to repeatedly pursue a good model.

Patience is undoubtedly key, but only if an investor can remain disciplined all throughout.

In the meantime, keep growing!

Excellent piece!

Thank you for sharing this. It is wonderfully constructed and very insightful.