What An Investor Needs To Outperform Over The Long Term

The premium subscription gives you access to all the content in Best Anchor Stocks, which includes…

All the deep dives

Recurring articles

Access to my real-time portfolio and transactions

Occasional webinars on various topics

A community of like-minded investors

A subscription the Premium + also gets you a quarterly Q&A with me to discuss anything you’d like.

If you want to know the type of content I share at Best Anchor Stocks you can read the Deere deep dive I uploaded a few weeks ago for free…

…or you can also read any of the other many free articles I have shared, just like this one!

You can also read the testimonials that existing subscribers have left. If you are a passionate and curious investor wanting to learn about high-quality companies, don’t hesitate to join Best Anchor Stocks!

Hi there!

Most investors that buy individual stocks are, in one way or another, aiming to outperform the market. If this were not the objective, it would be rational to buy index funds, taking less risk and supposedly enjoying great long-term returns (extrapolating what we've seen in the past).

A brief note here.

One Anchor (that’s how we call Best Anchor Stock subscribers) pointed out that this opening sentence is not entirely true. After speaking with him, I completely agree.

He mentioned that some individual investors don't really care about outperformance as long as they end up with a fair result because they enjoy the process. I am definitely one of such investors who enjoy the process and I imagine other people do as well, which is honestly refreshing to see in a world that only cares about financial outcomes. In this article, I focused on the financial outcomes because we can measure those, but I completely agree with this feedback.

Now, back to the article.

Others might argue that outperformance is not simply beating the market but beating it by a substantial margin so that the supposedly higher risk is worth it. While I understand the rationale behind this argument, slight outperformance over a significant period can definitely compensate for the higher risk.

Take, for example, investor "A," who achieves a 10% CAGR over the next 20 years by investing in index funds (not saying this will be the return indexes will achieve, just using some round numbers here). If this investor were to start with $10,000, the ending balance on their account in year 20 would be $67,275, equating to a 572% total return; not bad at all:

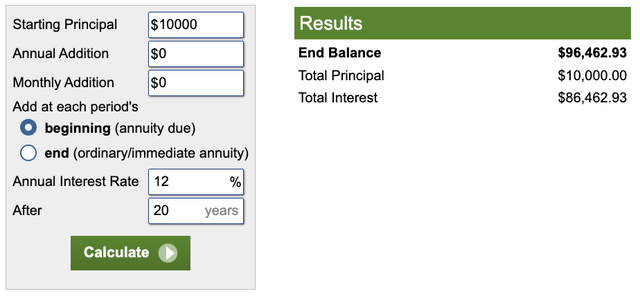

Then we have investor "B," who manages to beat investor "A's" index returns by 2% per year by investing in individual stocks, achieving a 12% CAGR. At first sight, this might look like a small difference because, at the end of year 1, investor "A" will have $11,000, whereas investor "B" will have $11,200. Are the increased workload and risk-taking worth it for $200? Not really. But what happens when we calculate the return of investor "B" over 20 years?

Investor "B" ends up with $96,462 in their account, an 865% return, or almost $30,000 (3x the initial principal) more than investor "A."

The further away we look, the more significant the difference is. Let's take 30 years. Investor "A" (10% CAGR) ends up with $174,494 in their account, a 1,645% return. Investor "B" (12% CAGR) would end up with almost $300,000 in their account, a 2,896% return. Slight outperformance works wonders if given enough time to compound.

These numbers suggest that if an investor invests long-term, trying to outperform the market makes sense because compounding will sufficiently compensate them for the increased risk of holding individual stocks.

But...how difficult is it to outperform the market?

Can an individual investor outperform the market?

The consensus view among investors is that outperforming the market over long stretches is almost impossible. For starters, there's data (which, by the way, is many times focused on professionals) showing that the average investor not only severely underperforms the market over long periods but even fails to keep up with inflation:

The other argument, which is more qualitative, boils back to the following:

If institutions spending billions on research can't outperform, what makes you think you can?

So, is outperforming the market easy for an individual investor? Well, it doesn't seem so, but is it impossible? The answer here is also a resounding "no." In this article, I'll outline those characteristics that I believe are necessary to outperform the market over the long term. Note these characteristics are common traits I have observed in investors who have successfully beaten the market over long spans. They also reflect my beliefs and my investing strategy relies on them but, unfortunately, I have not been investing for 20+ years (I'm turning 28 in a few months), so I have yet to experience it myself.

Before going into these characteristics, I'd like to discuss one advantage available to all individual investors.

Our time horizon advantage

Every time you read or listen to the argument of institutions' inability to beat the market despite having more resources than any individual investor, you should take it with a grain of salt. The rationale is that there's little overlap between how institutions can invest and how you can invest; the difference lies in the "perverse" incentives of the stock market.

While it has been well documented that investing is most powerful when the returns are achieved over the long term (thanks to the effect of compounding), Wall Street has been built over short-term incentives. The exact reason why this was done this way is difficult to tell, but it most likely stems from the fact that most of the firms on Wall Street make their money through transactions, not returns. Activity generates money for these companies, so inactivity (which is what long-term investing brings) is not well received.

A fund typically takes management and performance fees from its investors. The former is independent of the fund's performance in any given year, more recurring in nature, and is typically based on AUM (Assets Under Management). This means that the larger the AUM, the more management fees the fund takes. This incentivizes fund managers to grow AUM, and as competition is fierce, most resort to appearing in the top-performing funds every year, as these typically see significant inflows.

Long-term outperformance and constant yearly outperformance might sound like the same thing, but the truth is that the latter makes the former quite challenging. Every long-term investor must be prepared to underperform in any given year as a natural course of business. It happens to the greatest investors like Warren Buffett or François Rochon, who even has a rule for it:

We'll underperform at least one of every 3 years.

For most fund managers, having to wait many years to prove outperformance is too big of a toll, hence why they chase outperformance every year to drive AUM. Note that in a world ruled by immediacy, few investors are willing to give opportunities to funds that are not currently performing well, even if they are on track to do so over the long term. This makes the early innings of any long-term-oriented fund quite challenging, increasing the pressure on fund managers to focus on short-term performance.

The good news is that individual investors don't have to prove performance every year (as they are not chasing AUM) and can focus on what will be the ending balance on their portfolios over 10, 20, or more extended periods.

The bottom line is that you should always challenge the argument of your inability to outperform the market because professionals can't do it despite having more resources than you do. They undoubtedly have more resources than any given individual investor, but they are driven by widely different incentives, and thus the strategies are not really comparable.

It's also worth noting that this misalignment in incentives creates opportunities for the individual investor. Great companies will always go through periods where few will be willing to hold their stocks, fearing short-term underperformance. Say that Amazon (AMZN) is expected (it never can be predicted, but let me use this word anyways) to have a bad 2023 due to overcapacity lasting more than expected and fears of a potential recession. Many fund managers will sell it, fearing it will erode their returns. A bad 2023 should not be an issue for individual investors as long as there is conviction in the long-term thesis. Where Amazon's price ends up in 2023 should not matter much if you are willing to hold it until 2030; many fund managers "don't have" the privilege of thinking like this.

If you are enjoying this article and want to receive future articles directly to your inbox, make sure you subscribe!

What makes a good long-term investor

The advantage I have just discussed is not a characteristic per se of any individual investor but an advantage at everyone's disposal. An individual investor must decide if they want to take advantage of it or if they want to try to outperform the market every year. Note that the latter is more a question of ego than anything else because building wealth over a long period is not about proving how good you are every year.

So, what makes a good long-term investor? Note that these characteristics don't assure long-term outperformance but make it more achievable.

Filtering noise from signal

In a world increasingly dominated by data and immediacy, every investor is subject to a constant stream of news, all sold as "material" information. The media industry monetizes our eyes, so they'll do what's possible to attract them.

Many believe that markets have become more efficient with more information readily available to all, combined with algorithmic trading. The rationale is that there's abundant public information to help understand what a company is worth, and high-frequency trading moves current prices to intrinsic value much faster today.

While I have no strong evidence to support my claim, I believe it's the reverse: markets have become more inefficient with more data. Take, for example, Meta Platforms (META). The company's stock went from a high of $382 to a low of $89 and back up to $211...in under two years!

We are not talking about a microcap here; Meta is an almost $600 billion market cap company.

If you want more "evidence," I calculated the range of prices at which all the stocks in the S&P 500 traded over the last 52 weeks, trying to grasp volatility in stock prices. The average deviation from high to low for these companies has been a whopping 62%! The minimum trading range for any company in the index was 20%!

Does increased data and algorithmic trading make markets more efficient? Well, it doesn't seem so.

What's clear is that data has made long-term investing more psychologically challenging. For example, the average holding period of stocks has come crashing down since the introduction of the Internet and increased connectivity:

Easier access to investing and cheaper trading surely have played an important role in this holding period decrease, but I also believe increased data is to blame. What's the solution to filter noise from signal? Understanding companies we hold thoroughly and being aware that companies don't change every week.

Doing the homework in advance

More data and higher frequency trading create more inefficient markets, thereby creating more opportunities. However, these opportunities don't tend to last long for the same reasons, typically creating a short window for long-term investors to act.

Volatility alone does not create opportunities; it must be coupled with a prepared mind. This is why company research should be finished before the opportunity presents itself. Opportunities coupled with the absence of prior research can lead to FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) and low conviction, which inevitably ends in poor results.

Focusing on quality and never compromising it

Many studies show that stock market returns don't follow a normal distribution and are positively skewed:

This shows several things. For starters, it shows the power of asymmetric returns in the stock market. Stocks are theoretically unbounded to the upside but bounded to the downside. You can't lose more than 100% on any given stock (assuming no leverage), but you can multiply your capital several times over. This is why the stock market has performed great over the long term despite most stocks offering negative or poor returns. Simply put, most outperformers have more than compensated for poor performers and laggards.

Of course, now the question is:

How challenging is it to find those stocks that can offer "life-changing" returns?

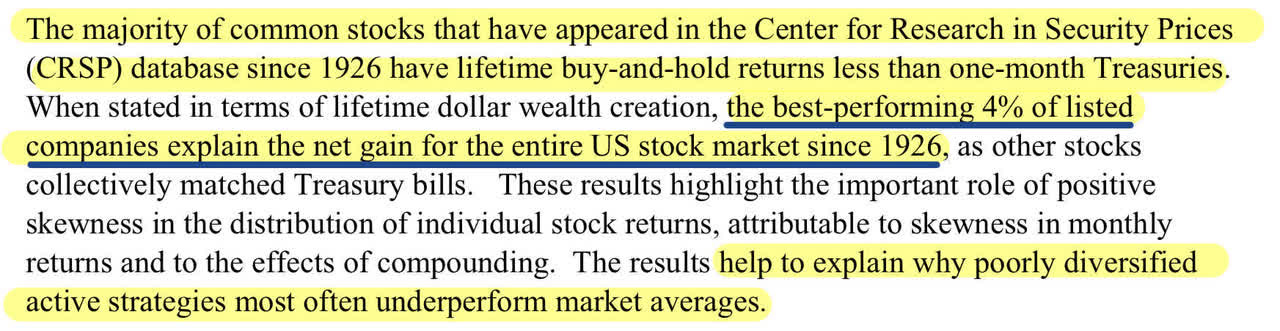

Well, it's not easy. According to a study by Hendrik Bessembinder, only 4% of stocks are responsible for all the stock market outperformance over treasury bills since 1926!

This offers several learnings. First, investors are more likely to own these stocks if they hold a diversified portfolio. Secondly, quality matters. While only 4% of stocks are responsible for all outperformance over treasury bills, this percentage is arguably much larger if we use quality businesses in the denominator. Of course, quality is very subjective, but many investors would agree in what a low quality company is. While these might perform well in any given year, they will likely end up underperforming over more extended periods.

This doesn't mean an investor can simply buy quality companies and let it be (any Beatles fans here?); all investments must be continuously monitored to screen those companies where fundamentals change significantly. Capitalism is fierce, and bad capital allocation can make even the highest-quality companies fall into the abyss. Sometimes an investor will be able to spot troubles early on, whereas other times, we simply must...

Be prepared to make mistakes

The asymmetric returns offered by the stock market are great because investors can compensate several losers with one winner, but it also means that investors will inevitably make mistakes. Unfortunately, being prepared to make mistakes is not easy, and only a few people will admit them and, most importantly, learn from them.

The interesting thing with investing is that some mistakes will only surface several years down the road, making it very challenging to look back and find the source of those mistakes. For this, investors might find an investing diary useful. The goal is to note down the rationale behind every decision to be able to come back at it when needed.

Mistakes are undoubtedly integral to investing, but extreme losses can have terrible consequences for investors. If one suffers a 90% capital loss, it will take years of outstanding performance to cover these losses and start the compounding process. The good news is that there are several ways to avoid (or to protect from) such losses. The first one of these is diversification. If an investor owns an equally-weighted 20-stock portfolio, a 90% loss in any of its positions will "only" wipe out 4.5% of its capital. The loss is severe, but its impact is minimized thanks to effective risk monitoring. The impact can be further minimized by weighing the portfolio according to the probability of permanent capital loss. Safer companies with lower upside should make up a larger portion of the portfolio than riskier companies with higher upside potential.

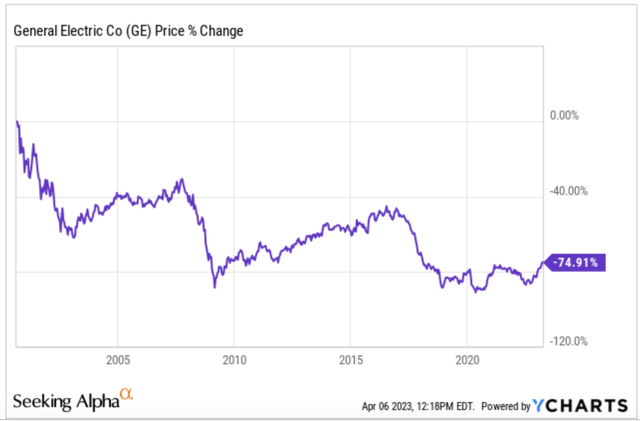

Another obvious "solution" is to avoid a 90% loss in any position. While buying high-quality companies at fair prices is a good starting point, the truth is that we never know how things will end up. For example, General Electric was a $600 billion company at its peak and considered an outstanding company, but it's down 75% since:

Going back to what I have already discussed: constant monitoring is crucial , and this is precisely what we try to facilitate at Best Anchor Stocks on top of the initial research. Very few companies have managed to remain high quality for decades, and the downfall almost always starts with complacency and lack of humility. These two downfalls are also present in investors. When someone has an excellent track record of performance, they might begin to believe they have this "game" figured out, which can lead to lax quality standards and, thus, a higher probability of making mistakes and eroding returns over the long term.

If you are enjoying this article and want to receive future articles directly to your inbox, make sure you subscribe!

Patience and persistence

This is an obvious one, and something that I believe to be innate. Compounding works wonders, but only when given enough time, so patience is required to let it do its work. For example, Warren Buffett made most of his fortune after turning 80 years old...was this because he got wiser? While I don't doubt he did get wiser thanks to all the experience, this can ultimately be attributed to how compounding works. Let's look at some numbers.

If an investor starts with $10,000 and doubles their money every 6 years (12.2% CAGR), they will "only" have $20,000 at the end of the first 6 years. This doesn't sound like much, but if this investor is willing to persist and think long-term, wonderful things can happen. After 12 years, the investor will have $40,000; after 18 years, the investor will have $80,000. The compounding curve is exponential. What will the investor have after 36 years?

The answer is $630,000. The crazy thing is that if the investor is willing to wait an additional 6 years, the balance in their account would be $1.2 million!

Patience and persistence are key to achieving such results, but only a few investors are willing to think that far out. I would like to tell you that these attributes can be learned, but I am more inclined to believe one is born that way.

Ability to think independently

The stock market is safer when valuations are depressed and riskier when valuations are at all-time highs. While this sounds like something obvious, many investors feel it's the other way around: safer when it's going up, riskier when it's going down. Part of this can be attributed to recency bias, as people feel the future will bring what the past has just offered.

One must be able to think independently to take advantage of opportunities driven by mania and avoid the market when it's in euphoria. Being a contrarian is sometimes challenging, but it's the only way to outperform. Now, I am not implying that an investor should do the opposite of what the market does or try to time the market. It's just that thorough work should allow investors to understand when a company is facing a short-term headwind leading to a long-term opportunity and when it is facing a secular threat. This is what I understand as independent thinking.

Conclusion

Slight yearly outperformance can have a tremendous impact on total return over extended periods. Achieving this outperformance is not easy, but an individual investor starts with a massive advantage: aligned incentives. From here, there are certain characteristics that make this outperformance more achievable, which can be boiled down to independent thinking, patience, and never compromising quality standards.

In the meantime, keep growing!

The 4% rule should be interpreted carefully as it relates to absolute amounts rather than percentage changes. If Apple doubles, it has a significant impact on the total value of the stock market, but it is 'only' a 100% return. Many mid-cap companies can increase tenfold without much impact on the overall market. The study also looks at how many stocks beat the t-bill percentage-wise, and that is much higher than 4%.

In the performance comparison at the beginning, it's not clear for me which one is for Anchor. Can you add a legend to the graph?