The Lindy Effect and Antifragility

Why the Past matters

Welcome to another post of the Best Anchor Stocks blog. This time I’ll look at the Lindy Effect, Antifragility and how it can be applied to investing. Many of what’s discussed here has significantly shaped my investment philosophy over the past years, and I believe that is something that all long-term investors should consider when building their portfolios.

The average age of the companies included in the Best Anchor Stock portfolio is 55 years, with the youngest company being 21 years old and the oldest being 150 years old. According to the Lindy Effect we should expect the bulk of these companies to survive for another 55 years, at least. Hopefully you’ll understand why after reading this article.

If your investment philosophy aligns with what is discussed here, be sure to check out Best Anchor Stocks, our investment research service focused on high-quality durable companies.

Without further ado, I’ll jump directly into the article.

There’s a mantra in the investment community which states that companies that have already won rarely qualify as worthwhile investments. I believe the rationale behind this thought process is that there’s little to gain from such investments as they are widely and (supposedly) closely followed. As such, these companies are always fully priced and leave little room for outperformance.

The skepticism revolving around proven winners not only comes from the above but also from traditional business theory. Corporate history taught us (sometimes through real experiences and others through pure business theory) that companies inevitably succumb to the forces of capitalism, leaving outsized returns in the rearview mirror and eventually reverting to the mean or fading into nonexistence.

Capitalism indeed serves as a strong gravitational force for outsized business returns. When a company earns outsized returns on its investments for a prolonged period, disruptors will come into the market (in case there are no strong competitive advantages) to take a bite of the pie. More players eating from the same pie eventually leads to less pie per player and, thus, lower returns per dollar invested.

This said, a special group of companies have been able to delay the forces of capitalism by building strong competitive advantages, making it almost impossible for a disruptor to take a bite of the pie. These competitive advantages come in several shapes and forms. If interested, I created the following graphic summarizing all the competitive sources identified by McKinsey:

So, everything seems to add up. I’m not discovering anything new here. Most companies that generate outsized returns eventually see these returns competed away until their Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) matches their Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC). When this intersection between ROIC and WACC happens, no other competitor will (technically) come into the industry, as it would lower the ROIC below the WACC, leading to value destruction. Simply put, at this point, the disruptor would make less money per dollar invested than what it costs them to raise that dollar.

Companies with strong and durable competitive advantages can defer this effect. But, what’s most interesting, some enter a reinforcing flywheel where the competitive advantages get stronger and stronger as time goes by. This phenomenon entirely contradicts business theory and is encompassed in the Lindy Effect, the subject of this article.

The Origins of the Lindy Effect

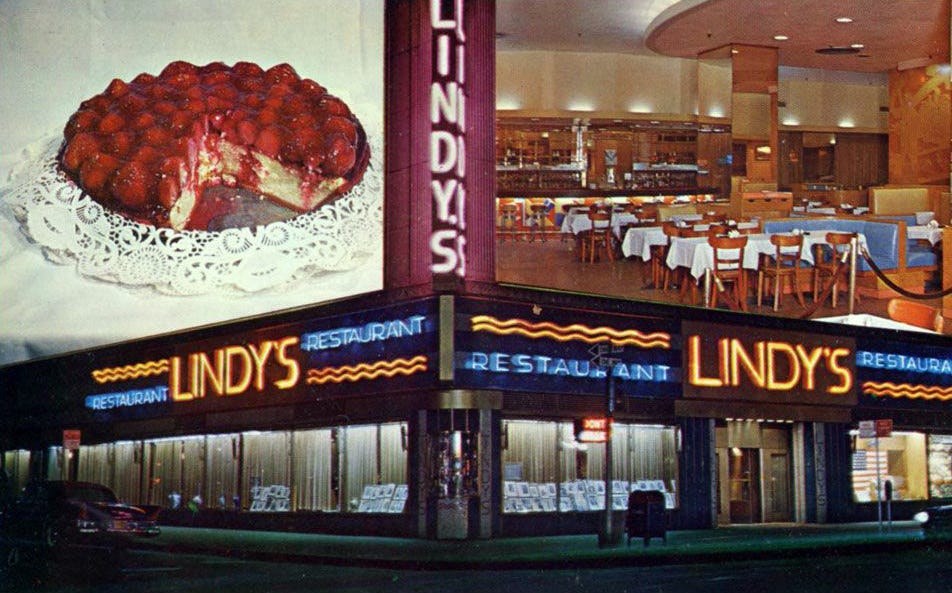

The term Lindy was born more than 50 years ago (1964) in an article (“Lindy’s Law”) published in The New Republic by Albert Goldman. The term Lindy came from the name of a New York City restaurant that hosted live comedy shows.

Unfortunately, the restaurant did not honor its name and ended up closing in 1969, but the effect that was born within perdured and is widely used today.

Contrary to what you might have imagined, Albert Goldman did not predicate or defend Lindy's law; in fact, he criticized it:

According to a law established and promulgated by bald-headed, cigarchomping know-it-alls who foregather every night at Lindy's, where always punctuating their talk with the same expression - a long, quizzically inflected "Fun-ny?" - they conduct post-mortems on recent show biz "action," the life expectancy of a television comedian is proportional to the total amount of his exposure on the medium.

If, pathetically deluded by hubris, he undertakes a regular weekly or even monthly program, his chances of survival beyond the first season are slight; but if he adopts the conservation of resources policy favored by these senescent philosophers of "the Business," and confines himself to "specials" and "guest shots," he may last to the age of Ed Wynn.

Benoit Mandelbrot reached a similar conclusion in 1982 to the “bald-headed, cigarchomping know-it-alls" that used to go to Lindy. According to Mandelbrot, the more appearances a comedian makes, the more likely they are to make future appearances.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb built off of Mandelbrot’s theory in his book “The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable” and finally coined the term “Lindy effect” in his book “Antifragile: Things that gain from disorder.”

What is the Lindy Effect and how it relates to Antifragility

Simply put, the Lindy Effect states that the future life expectancy of any non-perishable object is a direct function of its past survival.

For the non-perishable, every additional day may imply a longer life expectancy.

Source: Nassim Nicholas Taleb in "Antifragile: Things that gain from disorder."

According to the Lindy Effect, we can expect something that has survived for 50 years to live for an additional 50. Once this “something” turns 60 years old, we can expect it will live for an additional 60 years, and so on. The interpretation is that the more time something remains relevant, the further in the future we should expect it to stay relevant. It’s the prevalence of the old over the new.

According to Taleb, this “law” stems from “winner-take-all” scenarios. The rationale is that if an object has survived for decades, it has left behind a long stream of other objects that have perished, amplifying its advantage and raising its probability of future survival. Simply put, long-living objects have characteristics that helped them survive in the past and these characteristics should prevail in the future (there's nuance to this, of course).

Objects or things that perish typically do so because they are fragile to any given volatility shock or Black Swan events like a war, an unforeseen (like all) economic crisis, or a terrorist attack. Those that survive and come out stronger are considered Antifragile (a word coined by Taleb) as they gain from this volatility.

The Lindy Effect is intimately related to Antifragility. Why? Because we can place a higher probability of a more prolonged survival on something that we know has already survived several unexpected shocks or Black Swan events. The future is always unpredictable, so objects that are prepared and expect to profit from unpredictability should carry a higher life expectancy. The only way to prove this "preparedness" for unpredictable events is through past experiences. This is why the past is so vital to forecasting the future.

If you are enjoying this article be sure to subscribe to this blog. We would really appreciate it and it’s free!

Applying Lindy to investing decisions

I’m sure that most of you have read the above and made natural connections to investing (at least, that’s what I did while reading Antifragile over the past two weeks). You would’ve been right to do so, as the Lindy Effect is deeply tied to the concept of a durable business.

Many investors disregard the past when looking at potential investments, with the rationale being that investing is all about the future. While this is evidently true, this rationale makes many miss what the past can teach us about the future.

Take, for example, a 150-year-old company like Atlas Copco, a Swedish industrial conglomerate. Its long history can teach us little about its future operations (Atlas Copco is a very different company today than it was in 1873), but it can teach us a lot about its future resiliency to unforeseen events. That is, it can show us that Atlas Copco is Antifragile.

Throughout the last century and a half, the company has survived two World Wars, countless recessions, and a myriad of technological changes that promised to disrupt its business. So what has been the result? Atlas Copco has become stronger thanks to these Black Swans and is today a better company than in 1873. That’s Antifragility right there.

I know many will think there’s survivorship bias in this exercise, which is evidently correct. However, I believe survivorship bias gets negative connotations when, in fact, it is positive and de-risks investments. In the context of investing, survivorship bias means that time has done the work for us and is telling us what company has managed to survive unforeseen risks.

Don't get me wrong; there's much more than the past to assess future resiliency. A centenary company might go on to prosper in the future, or maybe not if it’s misguided. However, this doesn’t change the fact that the probability of it fading into obscurity due to an unforeseen event is lower than for a company that has not been tested by time (and thus has not suffered unforeseen events).

The thing is that many investors view companies as perishable objects, as if they had an upper limit to their existence. This observation makes little sense considering that there's evidence of companies that have not only survived for centuries but that have become stronger thanks to the test of time. Volatility is viewed as a risk in the investment world, but for many proven antifragile companies, it's a blessing.

Is the ratings industry the pinnacle of Antifragility?

One industry that is the culmination of Antifragility and exhibits Lindy-like characteristics is the rating industry. Rating agencies assess the creditworthiness of companies and governments and assign them a “grade” called a credit rating. Their customers then go to the capital markets and ask for financing with the cost of capital being largely dependent on this rating.

Customers have no choice but to pay for a rating of any of the Big Three (S&P Global, Moody’s, or Fitch), as the difference in funding costs between having a rating and not having one are substantial. The mission criticality of ratings and the value they provide give significant pricing power to rating agencies.

In the context of the Lindy Effect, the ratings industry, and the Big Three in particular, exhibit Antifragile characteristics. Note that we only know this because we have a past to look at, not because we can predict the future. Credit Rating Agencies are centenary businesses, but what's most surprising is how they have managed to survive unforeseen events that were created by themselves! Let's look at an example.

The Credit Rating Agencies (CRAs) played a significant role in the Global Financial Crisis of 2007/08. These companies gave triple-A ratings to complex structured finance products that, as we know in hindsight, were of low quality. These Triple-A ratings made it possible for many money market and pension funds to hold them in their portfolios. A while later, rating agencies realized their “mistake” (a bit tongue in cheek) and started downgrading these instruments, wreaking havoc across the financial industry.

This is what the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (FCIC) wrote in a later investigation:

The mortgage-related securities at the heart of the crisis could not have been marketed and sold without their seal of approval. Investors relied on them, often blindly. In some cases, they were obligated to use them, or regulatory capital standards were hinged on them. This crisis could not have happened without the rating agencies. Their ratings helped the market soar and their downgrades through 2007 and 2008 wreaked havoc across markets and firms.

The behavior by the CRAs was undoubtedly irresponsible, and if I were to stop the story here and you wouldn’t know what happened after, you would be lured into thinking these companies eventually failed and regulation was passed to make room for new competitors and make them liable for their behavior. The thing is that you’d be wrong (put mildly).

These companies not only perdured, they strengthened their competitive positions. They even went as far as forcing the government to revoke regulatory changes. The Dodd-Frank act aimed to make CRAs liable for their opinions (seems logical), but CRAs thought otherwise:

The legislative change was promptly revoked when the Big Three threatened not to authorize the use of their ratings in prospectuses and debt registration statements, causing severe dislocations in the market.

So, the Big Three survived and strengthened their competitive positions after a recession that was caused to a great extent by them. I don’t know what you think, but this seems pretty Antifragile to me.

I have read many people claiming that the main risk for CRAs going forward is reputational risk (i.e., getting ratings wrong), but if we look back, history seems to be telling us that investors shouldn’t worry too much about this risk. Looking at the future is essential, but so is looking at the past to assess the implications of future events. History rhymes but rarely repeats itself, so it's important to understand that the past doesn't tell us what will happen in the future, it tells us how companies react to unforeseen events, whatever they may be.

Conclusion

I hope this article helped you understand the Lindy Effect, Antifragility, and how both can be applied to investing. Investors constantly overlook the past when assessing the future, but it can teach us important lessons, especially regarding durability and resiliency.

I used to disregard the past thinking that a company has a finite life. While it's definitely true that few companies make it to 100 years of age, those that do have proven they can withstand and improve through volatile times, which are inevitable in the future. This is not a reason on its own to believe the future will be the same, but it's definitely a good sign.

In the meantime, keep growing and consider subscribing!

What a job mate!

A real pleasure to read you 🙌🏼

Great post! Thanks for putting in the work.