Two Attractive Industries That I Thought I Would Never Like

Before jumping right into this article, just a quick heads up. I wanted to let you know that I recently published the Best Anchor Stocks Annual Recap in which I do a brief summary of the year, showing my performance (you can see it below) as well as giving a glimpse of the composition of my portfolio.

I also wanted to let you know that I have published some thoughts on Amazon’s current valuation on Seeking Alpha. That article is also accessible for free using this link.

The premium subscription gives you access to all the content in Best Anchor Stocks, which includes…

All the deep dives

Recurring articles

Access to my real-time portfolio and transactions

Occasional webinars on various topics

A community of like-minded investors

A subscription the Premium + also gets you a quarterly Q&A with me to discuss anything you’d like.

If you want to know the type of content I share at Best Anchor Stocks you can read the Deere deep dive I uploaded a few weeks ago for free…

…or you can also read any of the other many free articles I have shared, just like this one!

You can also read the testimonials that existing subscribers have left. If you are a passionate and curious investor wanting to learn about high-quality companies, don’t hesitate to join Best Anchor Stocks!

Introduction

A couple of weeks ago, I told my subscribers that I would be making some additions to the watchlist from two industries. I discussed that one such industry was the water industry and mentioned that I would discuss the other industry in the coming weeks. I also "promised" that it would be somewhat unexpected.

This article aims to explain why I believe the cement and aggregates industries are interesting from an investment point of view.

It might surprise some that I chose to include an industry everyone thinks of as a commodity, but you’ll hopefully understand why I see it attractive.

In this article, I will…

Give some context on cement and its history

Explain if it’s a commodity

Explain why it’s interesting from an investment point of view and show some similarities with another industry that I have studied

Expose some of the problems that we can find in the cement industry

Talk about the two additions I will be making to the watchlist

As you can see, there’s quite a bit to go through, so let’s get on with it.

Where is cement used, and since when?

Many of you will know what cement is, broadly speaking. If we were to come up with a more specific definition for cement, we would say that cement...

...is a binder, a chemical substance used for construction that sets, hardens, and adheres to other materials to bind them together.

The main thing we can get out of this definition is that cement is seldom used on its own but instead together with other aggregates (you’ll understand this in due time) to form an end product. The better-known end product of cement is concrete, which is widely used in the construction industry.

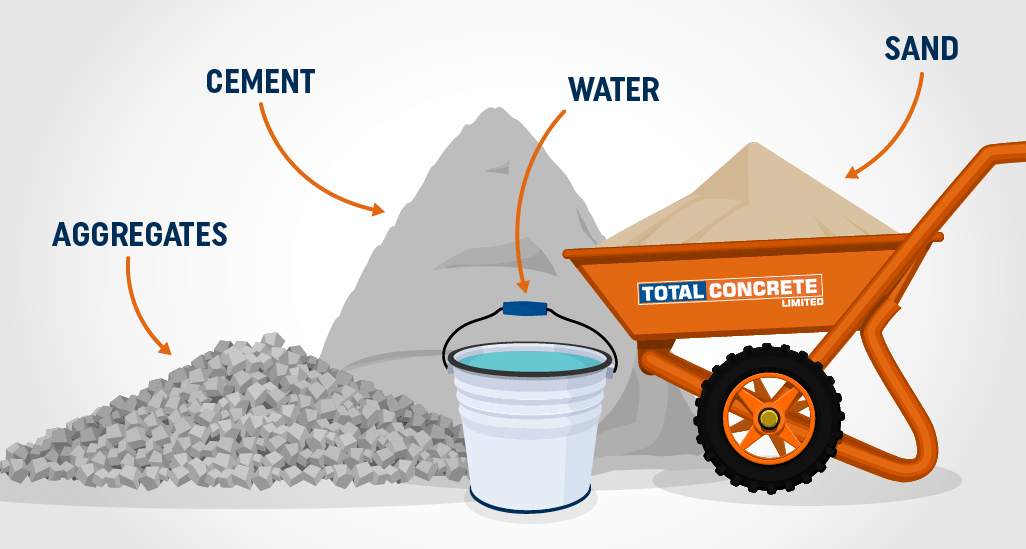

So, in short, cement is a material that is made up of several ingredients…

…which is later “blended” together with other materials to come up with an end product called concrete:

Concrete is widely used in the construction industry thanks to its inherent characteristics: durability, strength, and low cost. These characteristics have remained unchanged for centuries and humans have not found a replacement that can maximize those three variables as concrete does. The key probably lies in its cost:

It is composed of some of the least expensive materials available and thus has a major price advantage compared to anything which is based on organic chemistry. I think that will keep it as a top material for most of the types of applications it is used for now.

Granted, the cement and concrete we use today differ from those we used 2,000 years ago. The design mix of concrete has been tweaked and perfected, but the basic idea has always been the same: mixing materials to achieve durability and strength at the lowest possible cost. The first concrete-like structures date back thousands of years:

The first concrete-like structures were built by the Nabataea traders or Bedouins who occupied and controlled a series of oases and developed a small empire in the regions of southern Syria and northern Jordan in around 6500 BC.

The Romans and the Egyptians also used concrete-like structures to build their superstructures. Most of those buildings still stand today, demonstrating how durable these structures can be. Today, concrete is manufactured with Portland cement, which optimizes for strength, a sought-after characteristic in building infrastructures.

Is cement a commodity?

The answer is “yes” because the Portland cement manufactured by one company is equivalent to that manufactured by another company. This means there’s no differentiation between any given company's output. In fact, Portland Cement is standardized by the industry. This means that manufacturers don’t really have much flexibility in the end product.

Investing in commodities is dangerous because if there’s no differentiation, pricing is most likely to be the main criterion for customers. Why would a customer pay more for a product that is exactly the same as that of a competitor? The answer is they wouldn’t, which is why it’s tough to find high margins in commoditized industries. In such markets, intense competition tends to drop prices until it makes no economic sense to drop them further. This eventually means that most companies in commoditized industries don’t earn economic profits.

Then, why is it interesting?

Why is cement interesting if it’s a commodity and commodities are not interesting places to invest in? Well, several characteristics make commodity-like industries interesting investments.

The first one is found in the value-to-weight ratio. Simply put, if a product weighs a lot but has a low value, density and proximity become of utmost importance for cost. The reason is that transport increasingly becomes a more significant portion of the cost. Let me give a brief numerical example of this with some made-up numbers. If a commodity I am trying to buy costs $1 per piece, but every additional mile in transport adds 10 cents to this cost, then travel distance becomes an important consideration on my total cost. This means that the closest suppliers have a clear cost advantage. For example, this 25kg bag of Portland Cement costs 6 pounds, so obviously transport costs are very relevant in the equation:

This cost advantage makes it almost impossible for disruptors to come in because, in a commodity-like market, the winner is the lowest-cost producer, and the lowest-cost producer in industries with a low value-to-weight relationship is the one that it’s closest to customers. This sets a perfect scenario for local monopolies, precisely what cement companies are. It would make no sense for a competitor to come into a local market that an incumbent already serves as this would cause profitability to be negative for both companies.

In commodity-like markets, you can have two types of competitive advantages, both of which stem from costs:

You can be the lowest-cost producer by having an innovative production method

You can be the lowest-cost producer due to proximity

Both result in the same outcome (enabling the company to be the lowest-cost producer), but the durability of these two competitive advantages varies widely. The first one eventually fades as the competition catches up with the innovative production method, whereas the second one is pretty durable. There is no need to say which one of the two should be preferred by investors.

Industrial gas (Linde or Air Liquide), an industry that I have looked at closely and that interestingly has a good view from investors and Wall Street in general, enjoys similar dynamics. Industrial gas companies basically sell gas-related products that are not differentiated (with some exceptions like Helium). This means that density and proximity are of utmost importance because, even though gas does not weigh much, it does need quite a bit of space to be transported. This industry is another example of transport costs being very important in the cost equation and therefore in winning business. Industrial gas also has another commonality with cement in that it’s very durable. Gases have been used in industrial processes for a very long time, and it’s tough to envision a scenario where this changes.

There’s another moat that cement companies enjoy, which also turns out to be a potential risk (discussed later on): ESG. This “moat” is similar to that of Copart and revolves around NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard). Cement production involves the extraction of several materials, and the extraction permissions are not easily granted. This means that if a company has secured the extraction of any given material, it would be tough for a disruptor to come into the market and obtain similar permissions. For example, in the context of aggregates, it would take several years to obtain the necessary permissions to operate a new quarry:

Permitting for quarries are the limiting factor when trying to secure a new aggregates facility. According to Merrill Lynch, the permitting process can take up to 10 years and usually involves convincing the local community and regulators.

Source: Analyzing Good Businesses

Cement also enjoys two characteristics that results in stable pricing. Firstly, it’s mission-critical and has no substitute. Construction companies need concrete (to which cement and aggregates are inputs), and they have no other choice. Secondly, it makes up a low portion of customers' costs. This means that customers will look to cut costs elsewhere in times of turbulence. As you might have imagined, many commodities also comply with both characteristics but don’t enjoy stable pricing, so why is that? The answer is that other commodities have no moat, whereas cement does. This allows cement companies to pass on price because paying a higher price still makes more sense than sourcing the cement from far away (due to the aforementioned transport costs).

The evidence of a moat for cement companies can be found in their financials and their age. Many of the industry's companies are over a hundred years old and still enjoy good profitability. Another good sign is that many of these companies remained profitable during the Global Financial Crisis, which, as most of you might know, was especially severe in the construction industry. Something similar applies to industrial gas in terms of age and profitability.

All in all, despite being commodities, cement and aggregate producers enjoy attractive economics that allow them to enjoy strong moats and high barriers to entry. Low value to weight and NIMBY dynamics might be the only characteristics that allow commodities to enjoy strong and durable moats, and cement and aggregates producers enjoy both. Probably the best thing about this sector is its durability, a topic that I discussed in detail in my article ‘Durability and Its Implications For Investors.’

The “problem” with the strong moat

Ironically or not, there’s a problem with having such a strong local moat: growth. The reason is that they suffer the same barriers to entry when trying to enter other geographies than they enjoy when fending off potential competitors. This ultimately means that growth has to come purely from a given geography, exposing cement companies to the economic growth of that particular region.

Of course, there’s another growth lever: acquisitions. Take, for example, Constellation Software. As it operates in niche markets with significant entry barriers, it relies on inorganic growth to compensate for the low organic growth. Constellation also suffers the same barriers it enjoys when trying to grow. This growth driver has two potential problems:

It relies on management’s capital allocation skills

It’s tough to do at scale due to centralization and complexity

Constellation has solved both of these, but there’s no denying that organic growth is more profitable and less risky than inorganic growth. It's tough to envision a scenario where these companies can do acquisitions and the scale of Constellation. Note that there’s another possible solution to bypass this growth “problem:” buying such companies when they are cheap enough (ie., when there’s basically no growth baked in). Later on, when I discuss the companies that I will add to my watchlist, we’ll see a case of both (serial acquirer and organic grower).

The good news for the sector is that US infrastructure currently has an enormous investment gap, meaning that federal and state governments will need to spend significant sums in the coming years in renovating its infrastructure. According to The American Society of Civil Engineers, the investment gap is around $2.6 trillion which should be addressed over the coming decade. There’s a lot at stake…

In its 2021 report card [PDF], the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), an industry group, gave the nation’s infrastructure a “C-,” up from a “D+” in 2017—the highest grade in twenty years. Still, the group estimated that there is an “infrastructure investment gap” of nearly $2.6 trillion this decade that, if unaddressed, could cost the United States $10 trillion in lost gross domestic product (GDP) by 2039.

The US recently approved its Infrastructure Act to start addressing some of these needs. Of course not all of the gap will require concrete, but a good portion of it will. This investment gap will probably be a significant growth driver going forward but it will ultimately depend on how it applies to the different geographies as not all will receive the same level of funding.

ESG might also be a risk for cement companies because the manufacturing process is very energy-intensive and produces substantial CO2. Regulations and productivity are making the process more energy efficient, but ESG and current regulatory trends are definitely something to consider. Note, though, that the fact that this material is mission-critical for society and that there is no substitute ultimately means that we should not take this as too much of a risk. The only potential problem can come from not complying with regulations, resulting in fines or higher Capex to comply with such standards in the first place.

The additions to the watchlist and my thoughts on cement and aggregate producers

I decided to keep this part behind they paywall. If you are interested in reading it remember you have a 2-week free trial and a 20% discount using the link below!

Conclusion

I hope this article helped you understand the attractiveness of the cement and aggregate industries and why I have decided to add two companies to the watchlist. I will continue to do work on them and might bring more articles down the line, but I must say that bought at the right price (which I still don’t what it is), these can be great and durable investments.

In the meantime, keep growing!