The Traits of a High-Quality Company

And the characteristics that don't signal high quality

Hi reader,

I have wanted to write this article for a long time. Over the years, my investment philosophy has been tweaked here and there, but I have never lost sight of my objective of investing in high-quality businesses at reasonable prices (granted, this was not my investment style when my knowledge was lacking).

This begs the question…

What’s a high-quality company?

I believe this is a very subjective question to which no definitive answer exists. What might appear to be a high-quality business for a given investor might not fit the quality mold of another investor. This article aims to share my quality mold by describing the traits I look for to assert that a company is high quality.

It’s very important to note that it’ll be very rare to come across the “perfect” company, one that can be laid out as an “ambassador” of every trait I am about to share here. No company is perfect, but the good news is that perfection is not needed to enjoy business success. In fact, I’d go as far as to say that a company claiming to be perfect is probably as close to a red flag as you can get. Business success is much more achievable when a business acknowledges it’s not perfect and continuously works to solve its flaws and maximize its points of strength.

These are the traits that I have come up with:

I also discussed these traits (and others) with my good friend Drew Cohen, co-founder of Speedwell Research. We had a pretty detailed conversation about what makes a company great and ended up giving an example of the highest-quality company we have ever researched. The funny thing is that we both thought of the same company. You can watch the conversation on YouTube or listen to it on Spotify:

I would also recommend subscribing because there are more episodes coming from the Best Anchor Stocks podcast/YouTube channel.

Without further ado, let’s go with the first trait.

1. A good track record of past performance

If you have been following my writing for a while, you should already know that I care quite a bit about the past. This doesn’t mean that I believe the past is the only thing that matters when forecasting the future (needless to say, it isn’t). What it means is that I believe it can teach us more about the future than we can imagine.

It can ultimately show us what has made a business so special over the years and simplify our task as investors. The past will teach us about…

Operational and capital allocation discipline

The existence of a moat

The merits of the product or service

…

Does this mean we should take for granted that the future will be just like the past? No, not at all. It’s the investor’s task to judge whether what has happened in the past will be the status quo going forward.

I seldom invest in companies with a lousy past, and if I do, I have to be very sure why the future will be different. As Warren Buffett famously said…

Turnarounds seldom turn

Investing should not be a “game” of exceptions but rather of maximizing probabilities. I believe I am more likely to find a future outperformer among the companies that have done well historically than those that haven’t. There are, of course, exceptions, and these can be extremely successful, so we should never take things for granted.

Also worth noting that good past performance can be due to reasons entirely different from the reasons that might bring future outperformance. Take Danaher, for example. The company has been one of the best-performing stocks in history, compounding at a 19% CAGR (Compounded Annual Growth Rate) over more than 34 years:

Will this continue in the future? I believe it will, but we must not forget that the underlying reason for the outperformance will be much different. Danaher started its story by purchasing industrial businesses that it improved through the Danaher Business System. That was responsible for much of the company's success in the pre-2015 era, and it was mostly achieved by growing inorganically and improving the operations of acquired businesses. With the relatively recent refocus of the company toward bioprocessing and biotechnology, the story going forward promises to be more one of organic growth. The thesis has shifted, but the characteristics that made the business special in the first place have not. Some companies just find a way to keep winning…

Another not-widely-discussed element of studying the past is that it helps us generate implicit conviction (I recommend reading this outstanding article on the topic by Josh Tarasoff). Implicit conviction is not generated by believing an investment case makes sense based on the numbers and future projections but rather by believing that, whatever happens, the company will find a way to push through. Throughout our holding period, there will be tens if not hundreds of times that we will be “pushed” to selling, and it’s the implicit conviction that will ultimately allow us to remain invested during times of stress (which are inevitable).

In most (if not all) cases, past and future performance will be highly correlated with past and future capital allocation skills/abilities. Of course, there’s much more than this to great performance (for example, the unit economics of the industry the company operates in, luck,…), but there’s no denying that poor capital allocation will almost always correlate with poor performance.

Capital allocation goes beyond what the company is currently doing. A management team that is savvy in allocating capital will aim to maximize the output for every unit of input, regardless of the business the company is in. Danaher is also a great example here. The company has completely shifted over the last decade and is now positioned in a more attractive industry. This shift was only possible because management and the Rales brothers realized that the shift would maximize the company’s returns. Another example is Texas Instruments, which has divested several business lines throughout the last few years and has positioned its portfolio in the more attractive areas of automotive and industrial.

When assessing capital allocation, I typically look for companies that strive to get better, not bigger. Of course, a company with an excellent track record of capital allocation can (and probably will) grow larger as a result of great capital allocation, but growing should never come at the expense of improvement. With the entire financial world and incentive systems focused on getting larger, these companies are quite rare, but they do exist. It’s (almost) always a good sign to see management teams divesting certain business segments that don’t meet the company's quality standards. If few management teams are incentivized to make their companies smaller, few will (but I’ll touch on this topic later on in more detail).

All in all, I don’t think it’s wise to completely disregard the past even though we should invest looking forward. The past can teach us a good deal about the future. For those who claim that “everything is priced in for great companies,” I would tell them that most of these businesses have managed to outperform over very long periods, meaning that not everything was priced in at all times despite this view being the “consensus.” This might have to do with the fact that the market tends to undervalue durability.

2. The ability to generate outsized returns for a long time

Some of the traits in this article (like this one) will sound strikingly obvious to many investors, but I believe it’s important to write about them to understand what we should look for to judge whether a company is compliant.

Future growth is the variable that will most likely determine our long-term returns (so long it’s achieved in a value-enhancing manner), and there are two variables that matter in achieving future growth:

The returns the company is able to achieve when it reinvests into the business

The reinvestment runway ahead

(Brief note here: yes, valuation also plays a crucial role in forward returns, but over very long periods it’s the growth in earnings that matters the most, assuming we have not paid a crazy valuation. Some time ago, I shared this thread on X with an extreme example to show what I mean.)

The best-case scenario is one where the company invests increasing amounts of capital at incrementally attractive rates of return, but this doesn’t mean that a company must comply with both conditions. Some businesses enjoy great incremental returns but don’t need to reinvest significant amounts of capital to grow at a good pace. These companies are appealing because they can grow while generating significant excess cash that can be later paid out to shareholders. Later on I’ll explain why I don’t believe CapEx/reinvestment intensity to be such an important driver of quality.

The goal here is to answer the following questions:

Is growth generated in a value-generating way? And is it sustainable?

In my opinion, the two things any investor must look for to assess this are the moat and the opportunity ahead.

Looking at the moat should help us understand whether the value-generating characteristic of growth will be long-lasting. Capitalism is brutal, and very few companies manage to achieve outsized returns over the long term. Moats can come in many shapes and forms. Here’s a visual I built some time ago with some examples (the logos are not exhaustive, meaning there are lots of companies that have strong moats not included in the visual):

As for the reinvestment runway, several things are worth considering. Namely…

The growth of the industry

How the company will fare against this growth

Optionality

I don’t think these need too much explanation. If an industry is expected to grow fast and the company is expected to take market share in that industry, then it’s safe to say that the growth ahead is appealing (so long as this growth does not come at the expense of returns). Optionality is a tougher one, as it’s unlikely to be measurable due to its unexpectedness. Being unexpected, optionality can be the growth source that potentially offers the most upside to investors. The reason is obvious: it can’t be “priced in” to the extent that more predictable growth can.

In my opinion, there are two types of optionality: the one that can be somewhat expected (think about Apple launching the iPad or the iWatch or Copart transitioning into wholesale) and the one that’s impossible to foresee (think about Amazon launching AWS). Of course, the latter offers the most upside, but it’s almost impossible to forecast. This doesn’t mean that we can’t maximize our opportunities, though.

There are companies that continue to maximize their optionality through the years, so I’d say the probability of these companies uncovering new revenue streams is much higher than the probability of other companies doing so. You know what they say…winners keep winning. These companies tend to be built to continuously reinvent themselves and find new opportunities, which doesn’t ensure that optionality will be realized but surely maximizes the chances. If one reads Amazon’s proxy statement, one starts to understand why Amazon has managed to come up with multibillion-dollar businesses “out of thin air.” (I also tweeted something related to this topic).

Another thing that I also believe is very important to assess is the predictability of the future growth runway. It ultimately boils down to answering the following question…

Is the company in control of its destiny?

Some companies will be more in control of their destiny than others (none will be 100% in control), and I think it’s the former that any investor should strive to find. The reason is that this “control” greatly reduces the range of future outcomes, which ultimately significantly reduces terminal risk. Companies in control of their destiny typically exhibit the following characteristics:

They provide a mission-critical product/service

They operate a monopoly or an oligopoly

Their product/service makes up a low portion of costs

These characteristics ultimately result in high switching costs and resilience, meaning that the company will be more isolated from the economic cycles and it will have pricing power to grow profitable even during the toughest periods.

It’s quite ironic, though, that one of the companies in my portfolio that I believe is to a great extent in control of its destiny probably does not satisfy any of these conditions. This is something that I also discussed with Drew: one could possibly find exceptions to all these traits, meaning that they don’t hold the absolute truth.

The company which I am referring to is Hermes, which operates in the true luxury industry. If you want to read more about the company, I uploaded an article on it some months ago and also participated in a podcast with Sleepwell (not to be confused with Speedwell) at Chit Chat Stocks, where we reviewed the industry in general. This example simply shows that investing generalizations are dangerous, and it should always be a case-by-case analysis.

3. An experienced and aligned management team

Peter Lynch once famously said:

Go for a business that any idiot can run - because sooner or later, any idiot probably is going to run it.

While I understand what he was trying to say here (that a company should be much more than its management team), I believe management is an important part of any company. A lousy management team will not break a company, but maybe two or three consecutive lousy management teams will, especially in the fast-changing world we currently live in.

Note that we should never disregard opportunity cost, not even when talking about this topic. It’s all about return maximization. While a management team run by an idiot might not break a great company, there’s no denying that a great management team will probably maximize its growth and return to an extent that the idiot will not. This is why focusing on management quality and experience is important.

Alignment is another key topic. Someone famously said, “Show me the incentive, and I’ll show you the outcome,” and I believe this quote has been confirmed time and time again in the stock market. When a management team has perverse incentives, the normal outcome is one that’s not good for shareholders. Conversely, if a management team has the right incentives, the right outcomes are not ensured, but they are more likely to become a reality.

I typically look at alignment through two lenses:

Compensation structure

Insider ownership

The ideal scenario is that a company has both high insider ownership and a great compensation structure, but this does not need to be the case for every company. We must understand which one is more relevant. This relevance varies markedly across companies. For example, the Hermes family owns around 60% of the shares outstanding and has a commitment to hold at least half of these shares until at least 2041. There’s no denying that the compensation structure here is not very relevant because they will probably maximize their holdings more than meet short-term incentives that result in significantly lower payouts (compared to a substantial stock price increase over the next 10 years).

On the flip side, Deere’s insiders don’t own a large chunk of the company, and they can cash out tomorrow if they want, so the compensation structure is much more relevant here than for Hermes. The goal is obviously to understand if managers have the incentive to increase the share price over the long term, regardless of the source of these incentives. The right incentives increase the probability of achieving the right outcomes, so I believe it’s something any long-term investor should care about dearly.

4. Survivability

I believe this trait can be divided into two sub-topics:

A strong financial position

Resilience during recessions

Both have the same goal of allowing a company to survive for a long period and to comply with the first rule of compounding (according to Charlie Munger):

The first rule of compounding: Never interrupt it unnecessarily.

Let’s start with a strong financial position, which I believe can be a bit controversial. Bankruptcy strikes me as an event that can interrupt compounding, more so when the company is not returning money to shareholders. The reason is that bankruptcy can potentially make all the retained earnings be worth zero. Therefore, a company that has not returned the money to shareholders is worth zero regardless of all the growth achieved before bankruptcy:

If a firm never pays out dividends and then goes bankrupt 20 years in the future, from a financial theory standpoint the company is worthless today.

Souce: David Giroux’s ‘Capital Allocation’

A strong financial position is a company’s only way of protecting itself against bankruptcy. Some business models are evidently more resilient and durable than others (more on this later), but the reality is that a company does not know…

When a Black Swan event will take place

How this Black Swan will impact its business

We should not forget that all it takes for the compounding process to end abruptly is a Black Swan event that comes at an inappropriate time. Granted, the probabilities are fairly low (thus why it’s called a Black Swan), but some companies prefer not to risk it.

This brings a debate among shareholders/investors, as some might prefer an efficient capital structure that maximizes current returns over a balance sheet optimized to maximize the length of such outsized returns. Arguments favoring both are valid and ultimately depend on an investor's time horizon. If an investor’s holding period is one year, then it’s normal to see them choose the efficient capital structure over the pristine balance sheet. On the contrary, if an investor’s time horizon spans decades, then he is better off with a pristine balance sheet to maximize the durability of those returns.

A recession also strikes me as an event that may not end up in bankruptcy but can temporarily impair a company’s ability to carry out its strategy. The reason is that if the business is not resilient during a downturn, it might be forced to save cash at a time when the best option is clearly to invest countercyclically. Note that this ability to reinvest countercyclically might also come from a strong financial position, not necessarily a resilient business. Good companies tend to become stronger during downturns only if they are able to go against the herd.

5. Customer obsession

Every company has customers, and while some might believe their customers have little bargaining power (which might be true today), ignoring them is a terrible long-term choice. You never know what will happen in the future, and a loyal customer base is a very strong asset for several reasons.

First, word of mouth can greatly impact a company’s business, and it’s free. Second, customers with a high lifetime value are very profitable because acquisition costs are incurred once, and these customers are “milked” for many years. What’s also interesting is that treating customers well can substantially lengthen the moat. Let me explain how using an example.

One would argue that ASML does not need to focus too much on its customers because it has a monopoly in EUV, meaning customers have no choice but to buy the company’s equipment. While treating them poorly would not erode the company’s moat over the short term, it might lead customers to finance other projects to displace ASML’s technology (i.e., they might be incentivized to look for alternatives, even if they don’t exist today). However, ASML is well aware of this and works hard to please its customers and ensure they enjoy great profitability despite the elevated cost of its systems. This way, customers don’t have a reason to look elsewhere.

Regardless of a company’s competitive position, one should never treat customers poorly because it’s not the strategy that maximizes returns over the long term.

6. A strong culture

This is a purely qualitative trait and, honestly, one that I don’t think is measurable at all. However, we can’t undermine its existence and importance, especially since most long-term compounders have something that has made them different from their peers (besides excelling at the rest of the traits I have already discussed).

What’s interesting is that, in my view, culture is not the important thing in itself. The important thing is for how long a company manages to defend its culture. Note that companies that have been operating for decades are likely not in the same business today as they were several decades ago, but the culture is the glue that ties the company together and serves as the common denominator during both periods. Great examples here are Atlas Copco and the aforementioned Danaher. Danaher might have shifted its core business through the decades, but the Danaher Business System has remained immutable and helped the company succeed regardless of its current business.

The only problem with searching for a strong culture is that it’s very tough to find and normally requires years or decades of following the company until it can be fully understood and appreciated. To this, we must add that it’s tough to come across strong cultures unless…

The founder is still involved

Employee retention is very high, and managers are hired from within.

These two characteristics are rarely found in the modern world, and they are even rarer when one searches for companies with a reliable track record (as these companies tend to be quite old). The good news is that we don’t need hundreds of companies to comply with these characteristics to build a strong portfolio.

7. Long-term orientation

This might sound like yet another obvious trait, but I don’t think it’s the norm in today’s financial markets. It honestly all goes back to incentives, management continuity, and the market’s gravity.

If a management team is going to run the company for only 5 years and the incentives are not appropriate, it’s somewhat normal to see them focus on the short to medium term rather than the long term. However, if incentives are right and management teams are able to operate the company over the long term, it’s normal to come against long-term orientation. Take, for example, Deere. The average tenure of the past 5 CEOs has been around 8 years, which is pretty high for current standards. What I like to call “CEO shuffle” is one of the reasons why many companies never focus on the long term.

Adobe is yet another great example. Shantanu Narayen has led the company for 17 years. One starts to wonder if a CEO who expected only to remain in his position for 5 years would’ve conducted the shift to SaaS that Shantanu started in 2008. Success was not immediate, and the transition was a bumpy road, but management knew they would most likely be at the helm to see their efforts bear fruit.

One thing that I believe results in (or at least facilitates) long-term orientation is not setting short-term guidance or expectations. Most companies on Wall Street have grown accustomed to giving the market quarterly guidance (even when forecasting is the task of the investor), which can lead to some perverse behavior and short-term orientation. Most financial frauds in history had “the need to meet guidance” as a common denominator. This said, setting long-term targets can be very positive and demonstrate long-term orientation from the management team. Long-term thinking is contrarian thinking nowadays (even if many people want to make us believe it isn’t).

There’s no shortcut to assess long-term orientation; my preferred method is reading the earnings calls of at least the last 10 years. This has several beneficial effects:

It helps you grasp the evolution of the business much better

It helps you understand if management has complied with past promises and the quality of the foresight

What I don’t think is THAT important when looking for a high-quality company

While writing this article, I also thought it would be a good idea to discuss certain topics that I believe are typically understood as traits of high-quality companies but that I don’t think necessarily correlate strongly with them. I’ve been able to think about two (feel free to leave others in the comments below).

Capital lightness

Many people believe that a high-quality company must be capital-light. While I understand their arguments, I have not found this to correlate strongly with the presence of quality.

There are many high-quality companies that are pretty capital-heavy, but that are able to generate significant sums of excess cash and where the capital intensity serves as a moat. Of course, Amazon is the perfect example: it’s almost impossible for a competitor to replicate its distribution network at this point. What’s interesting is that the Capex-heavy distribution network has allowed the company to come up with a few capital-light businesses like subscriptions and ads, making capital intensity naturally decrease over time.

Investors should also strive to understand what portion of the current Capex is related to growth and what is maintenance. Some Capex-heavy companies might only be capital-heavy while they have abundant reinvestment opportunities. A good example here is Copart, which probably does not need to spend much on land once the growth opportunities abate.

There’s no denying, though, that the preferred scenario is a capital-light company with a very strong moat. These companies are able to generate good growth while having a lot of money left over for shareholders. The only downside I see to such businesses is that management has to be willing to give that excess cash to shareholders in a way that makes sense. Many businesses that generate tons of cash don’t want to signal that they are out of reinvestment opportunities by establishing a dividend. They might repurchase stock at unattractive valuations or, worse, purchase other assets at a hefty price to make their business larger!

High profit margins

Many people claim that the higher the profit margins the better. While I do agree with that if all things are equal, I don’t think that the level of current profitability is as indicative of quality/no quality as many believe.

For starters, it’s not about the margin per se but how defensible that margin level is. An investor would probably achieve a better outcome investing in a company with lowish but sustainable margins than investing in a company with high margins that are not entirely protected from competition. Logical conclusion, I know, but something always worth keeping in mind when analyzing companies that boast strong margins is that the moat needs to be very strong because those margins will probably be appealing to many potential competitors (i.e., “your margin is my opportunity.”)

Secondly, it’s about the margin's resilience. A company with low margins might appear fragile if we were to go into a recession, but that highly depends on the business's resilience. In short, just because a company enjoys a 20% net income margin doesn’t mean it will remain more profitable during a recession than a company with a 10% net income margin.

Finally, the current margin level might be self-induced and, therefore, not indicative of the actual earnings power of the business. Two companies that have followed scale economies shared (through which they have shared their margin with customers) that have done great are Amazon and Costco. Their margins might appear pretty low, but the earnings power is substantially greater.

While, all things equal, I believe that high margins might be better than low margins, I don’t think the argument is as black or white as many people believe it is.

The Best Anchor Stock portfolio through a quality lens

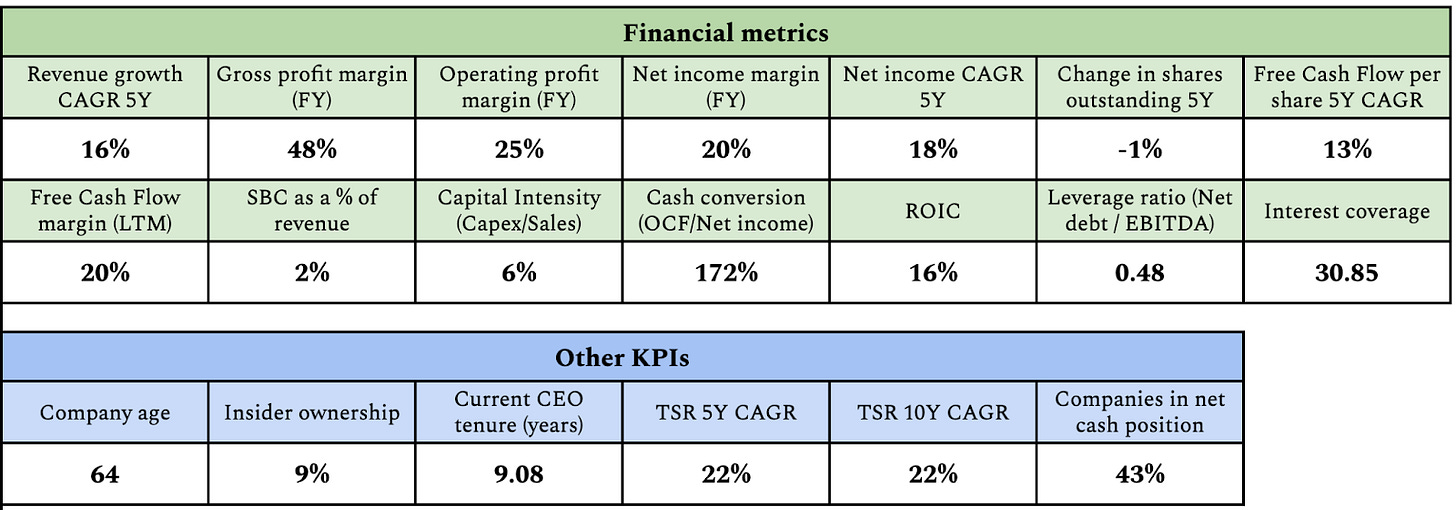

After reading Terry Smith’s shareholder letters, I thought it would be a good idea to build a quality table with the companies in my portfolio. Of course, you might disagree with the variables I assess quality against, but here they are:

This shows portfolio-weighted averages, so obviously there are large discrepancies across the companies in the portfolio. If you want to have access to all the companies and the research, don’t hesitate to subscribe:

Conclusion

I hope this article helped you understand what I understand as quality. As discussed at the beginning of the article, I don’t think many companies will be ambassadors of all traits. There are certainly high-quality companies that don’t comply with these (some of them are in my portfolio). This doesn’t mean the traits are not useful, as they will help us maximize our probability of finding a high-quality company.

In the meantime, keep growing!

Disclaimer: As of the moment of this writing, the author might have positions in the securities discussed. The article is intended with information purposes only, do your own due diligence.

i truly appreciate the time & effort put in this article! keep it up

Great post, Leandro!