You can read the PDF version of this deep dive here.

Hello and welcome to Best Anchor Stocks,

I thought it would be a good idea to release one of my deep dives to the public so you can get a sense of the type of content I share behind the paywall at Best Anchor Stocks. Deere is the last company I added to my portfolio, and thus it remains quite relevant. Note that the Deep Dive you will be reading here is not organized in exactly the same way I organize it for Best Anchor Stocks subscribers. For these I typically break down the deep dive into 5 or 6 articles, although the content you’ll read here is exactly the same that was contained in those 6 articles.

This is the outline for this deep dive:

Section 0 brings a brief introduction and a short investment thesis.

Section 1 will discuss the company’s long history and what it does.

Section 2 will dissect the financials and growth drivers. The financials are very misleading for Deere unless one puts in the extra work. You should be able to understand why once you read this section.

Section 3 goes over the competition, the moat, and the risks for the company. These are three key topics for any company, especially when looked at through the lens of a long term investor.

Section 4 will discuss yet another three key topics: management and incentives, capital allocation, and valuation. Just like the financials, capital allocation is a somewhat misleading topic for Deere as the consolidated number misses the inherent return profile of the company’s equipment business.

Section 5 will bring my thoughts on cyclicality and where the company stands today.

Finally, section 6 will go over how Deere complies with the Best Anchor Stock traits. These traits help me adhere to my investing philosophy and therefore are very important in my process to make me stay within my guidelines.

Without further ado, let’s get on with the deep dive.

Section 0: Introduction and the short investment thesis

In the past, we would rely on planting more acres, increasing horsepower, and applying more nutrients. In short, we could always do more with more. However, today, in agriculture, we must do more with less, and our ambition at John Deere is to help our customers do exactly that.

John May, John Deere’s CEO, during the most recent Investor Day

I imagine you might be familiar with Deere’s most recognizable brand and somewhat familiar with what the company does…

I researched Deere for a couple of months and ended up growing comfortable with the investment thesis, which can be briefly summarized in the following characteristics:

Low probability of permanent loss of capital over the long term

A very decent probability of earning a double-digit return long-term

Upside optionality from technology and multiple expansion (not counting on this for the thesis, but it can potentially amplify the returns)

At first sight, Deere might seem like a low-growth, boring company, but the company is currently in the midst of a transition that will not only bring faster growth but also a transition to higher quality and more recurring profits. You’ll hopefully understand what I mean by the end of this deep dive.

Before going right into the company’s history, here are some basic facts about Deere:

Before jumping right into the company’s history I thought it would be a good idea to share my short investment thesis, which will be then outlined in more detail throughout the deep dive.

1. Deere is becoming a better business

Deere is transitioning from just selling equipment, maintenance, and parts to selling solutions that will be monetized through a recurring revenue model. This will have a profound impact on the company’s quality and cyclicality:

We are confident in our ability to produce higher levels of returns through the cycle while dampening the variability in our performance over time. This will lead to higher highs and higher lows for our business.

Josh Jepsen, Deere’s CFO during the 2023 call

2. A durable and growing business

Few things are more durable than feeding the population, and I believe most of Deere’s industries will enjoy long-term secular tailwinds. Deere has been around for almost 200 years, and I don’t foresee a scenario where the company is not with us for much longer. In my opinion, the company has a high terminal value and is poised to benefit from the technological trend thanks to its installed base.

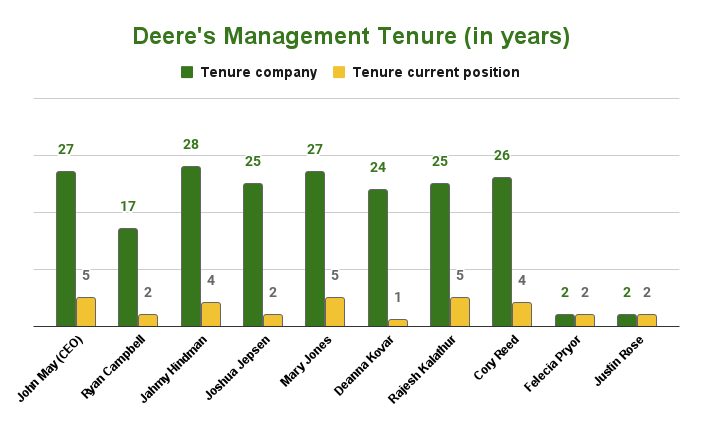

3. A very strong moat and an aligned management team

Deere has a very strong moat (explained later) and an aligned management team (also explained later). These characteristics significantly reduce the variability of future outcomes and terminal risks. It’s a sleepwell investment for me, irrespective of the cycle.

4. A reasonable valuation

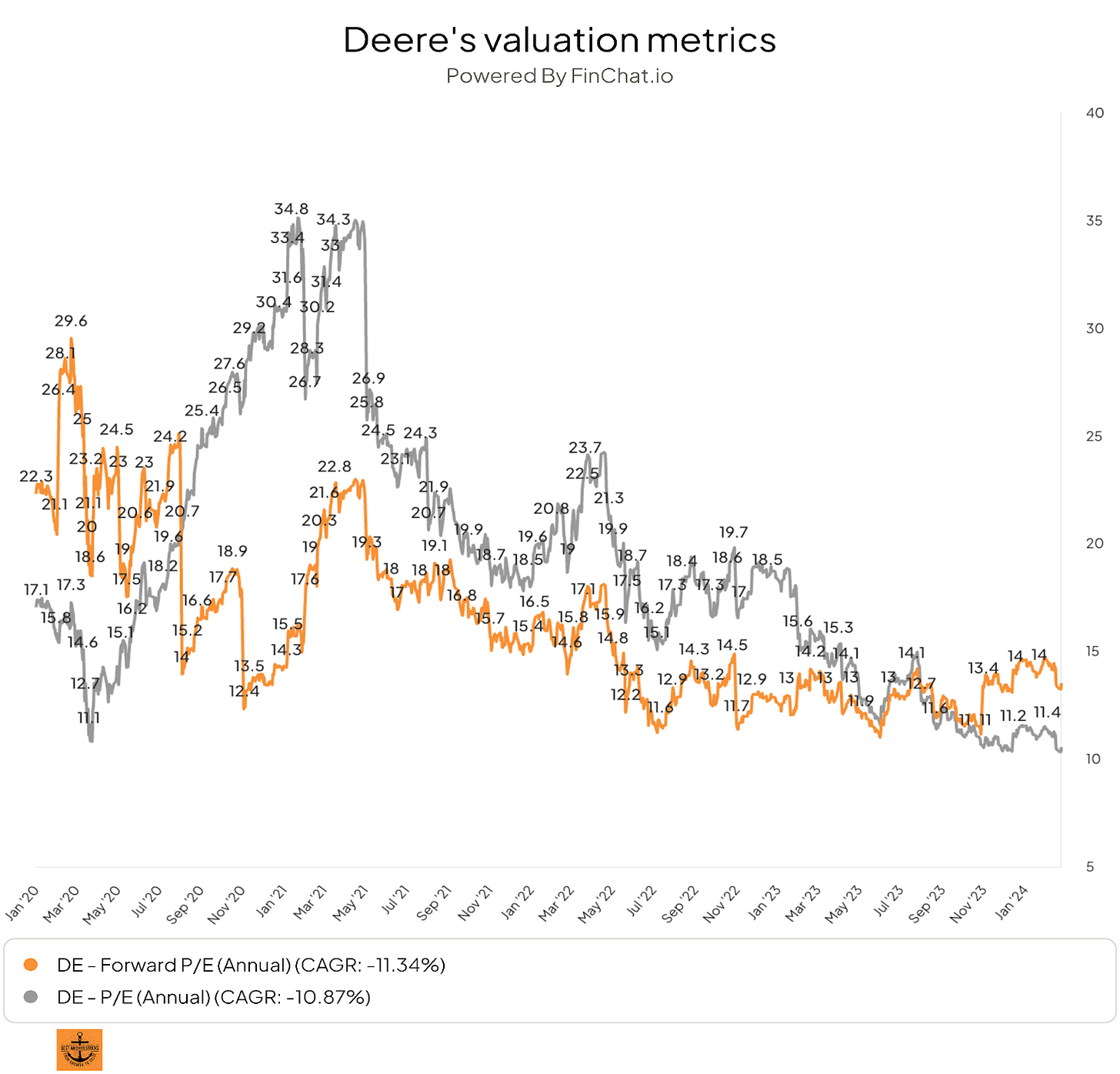

Deere is a cyclical company, which makes valuation a dangerous topic. Cyclicals tend to appear cheap at cycle peaks and expensive at cycles throughs, and Deere right now looks optically cheap. The company is currently trading at a forward PE of 14, and a trailing PE of 11 as sales and profits will most likely drop this year:

Source: Finchat.io (you can get yourself a 15% discount using this link)

Shouldn’t this be a warning sign for a cyclical? The short answer is yes, but I would also caution against looking at prior cycles to judge valuation. Several reasons behind my reasoning:

Deere will remain more profitable through the current cycle than in any cycle in the past, meaning that past multiples are misleading as the company should, in theory, command higher multiples today.

Management argues that after this year’s drop, the company will be trading around mid-cycle earnings, meaning that the company might be trading at a normalized PE multiple of 14 times, which does not seem expensive at all.

Management has guided to $5.5 billion in Free Cash Flow this year. If this is mid-cycle, the stock is currently trading at a 5.5% normalized FCF yield, which is not expensive. We can see that a double-digit return is doable if we add the expected FCF growth rate to this normalized FCF yield (to calculate our expected returns).

Let’s say Deere grows its revenue at a 3-5% CAGR through the cycle (1-3% tends to come from pricing). This doesn’t strike me as optimistic, considering the company achieved a 5% CAGR from peak (2013) to peak (2023) in the prior cycle. To this, we have to add the margin expansion the company will enjoy from pricing and technology, meaning it might grow its earnings at around a 5%-7% CAGR through the cycle. If we add this growth rate to the current cash flow yield, we get an annual return of around 10.5% to 12.5%.

This return would be achieved being conservative and without counting on multiple expansion, which can be a part of the equation as the company’s transition will make it a better business. I don’t know what the current cycle will bring, but I do believe Deere is fairly valued if we take a long-term view. Should the market punish the company for a worse-than-expected cycle I would most likely take advantage of it, which could also amplify these returns.

Without further ado, let’s jump right into the deep dive.

Section 1: History and what the company does

Ironically or not, Deere was founded in 1837, precisely the same year as Hermes, the oldest company in my portfolio. This makes Deere the oldest company in the portfolio together with the French luxury house, something that should be considered a mere coincidence (but an interesting one nonetheless). Their founding year is probably one of the few things these companies have in common, which portrays one of the things I like the most about investing: excellent companies and investments can be found in widely different industries operating under widely different business models. In short, quality can take many shapes and forms.

Deere was founded in 1837 in Illinois by blacksmith John Deere, with the company still bearing his name to date. Worth noting is that Deere is very proud of its heritage, which has served as the bedrock of its values, culture, and how the company views its relationships with its customers. Proof of this is the fact that the headquarters are still located in Molines, Illinois, the place where John Deere decided to establish the company in 1848.

The first product John Deere ever commercialized was a steel plow. Plows existed back then, but they were typically made of cast iron. This material brought a significant problem to farmers: the soil in Illinois was characterized by its stickiness, so farmers had to spend quite a bit of time cleaning the soil of their plows every couple of feet. John Deere did not invent the plow, but he came up with one that enabled higher productivity. The steel plow gathered a lot of attention from farmers:

Many cite John Deere’s invention of the steel plow as the beginning of a revolution in America’s farmland, and for good reason. The product was a commercial success, soon selling 2,000 units a year. It also underscored what Deere remains focused on even to this day: making farmers more productive and, therefore, more profitable.

It was not until 80 years after its founding (1918) that Deere would enter the market it is known for today: the “heavy” equipment market. The company launched two tractor models that year, although once again, it built off the innovations of others. Those years were characterized by the arrival of mechanization to American farmlands, and just like Hermes (that diversified away from horse accessories due to the arrival of the car), Deere had to reinvent itself to adapt to the shift away from horses (maybe these companies have more in common than we think!). The company tried, at first, to develop its own tractor model but ended up capitulating and buying the Waterloo Gasoline Engine Company, famous for the production of the ‘Waterloo Boy’:

The company gathered expertise from this acquisition and decided to manufacture tractors under its own brand. Deere launched the Model B tractor, which remained a best-selling tractor for 15 years:

Deere then embarked on several decades of innovations through which the company improved existing products and launched new ones, all with the same objective of increasing farmer productivity and profitability.

Especially of note was Deere’s transition to more powerful equipment throughout the 20th century. Farmer needs were shifting as the population grew, requiring more powerful equipment; Deere delivered. The company showcased its “New Generation of Power” in 1960 to many dealers and farmers worldwide. The event gathered a lot of attention and kickstarted a new era in the company’s history:

Power kept the company busy for the next 4 decades, but the arrival of technology at the end of the century marked yet another revolution inside the company. Deere acquired Navcom in 1999, a pioneer in GPS technology. The company soon started deploying this technology across its machinery. From that moment on, technology became a focus for Deere, a venture in which it continues to invest heavily to this day.

The company focused its efforts on improved equipment and technology for a great part of this century, but 2017 also brought a significant event: the acquisition of the Wirtgen Group. Deere purchased Wirtgen for $5.2 billion, its largest acquisition ever by a considerable margin. The acquisition provided Deere with a stronghold in the construction machinery market, more specifically in road construction, a segment where Wirtgen was a world leader.

This niche market enjoys significant synergies with agricultural equipment (both in manufacturing and technology) and is also expected to enjoy strong tailwinds (more on this in section 2).

What should stand out from Deere’s history (and what also makes it somewhat comparable to Hermes) is that despite the ebbs and flows in its operations and industries, the company's core has never changed. This was partly facilitated by the Deere family, who ran the company for most of the 20th century. The family is no longer involved but managed to build a culture that has endured across many CEO tenures. Key here has been the company’s policy in leadership continuity (something that I’ll discuss more in-depth in another section).

Deere remains focused on making farmers (and other customers) more productive; the only difference is it now targets increases in productivity through technology rather than materials and power. The times have changed, but Deere’s core has not. As Deere’s former CEO Hans Becherer rightly pointed out…

This company is bigger than all of us. We just want to effectively pass it from one generation to the next.

As you’ll discover throughout the deep dive, “longevity” and “generation” are two essential words for the company and its customers.

What Deere does

So, what does Deere do? I’ll try to simplify it as much as possible so that it’s understandable, although I think the company is not very complex. At its core, Deere manufactures heavy and semi-heavy equipment for the agriculture, construction, and forestry industries.

The company operates across four segments, three of which comprise its equipment operations, with the other offering financial “support” to these:

Before digging deeper into these segments, I would like to outline several commonalities across the company’s equipment operations. Firstly, they all have a cyclical (to a greater or lesser extent) component of equipment sales. These equipment sales are complemented by a maintenance, service, and parts component, which can be considered somewhat recurring (although not all the segments are exposed to this recurring source to the same degree). AGCO, one of Deere’s competitors, has never had a down year in service and parts, which speaks greatly to its resilience. Thanks to technology, Deere (and the industry as a whole) is transitioning into a predictive maintenance model that diminishes downtime. Downtime minimization is especially crucial in agriculture as most of the profits are generated in relatively short periods when the equipment must operate at its full potential.

Unfortunately, management does not disclose what portion of equipment operations sales comes from equipment sales and how much comes from recurring revenue sources. Still, they expect the recurring part to make up around 40% of the business by the decade's end.

Secondly, most of the company’s equipment operations are supported by its dealer network. This dealer network is typically exclusive and offers its customers selling, support, and maintenance services (the dealer network will be discussed in more depth in another section).

Let’s dig a bit deeper into each segment.

(a) Production and precision agriculture (PPA in short)

Deere sells mid and large agricultural equipment and precision farming technologies through its PPA segment. These products and solutions target large farmers, as these typically require high horsepower machines (large ag equipment) to farm their lots and also get outsized returns from even minor yield improvements (precision agriculture). Volume and scale tend to be key characteristics of PPA’s customers.

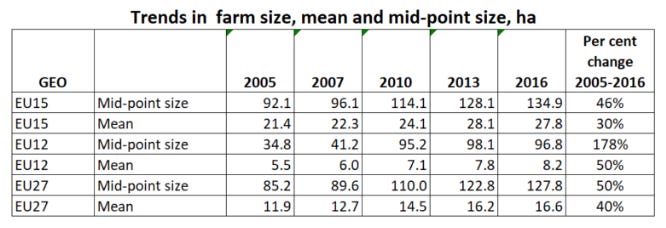

Deere spent significant time and money throughout the 20th century creating large equipment that would suit US farms. According to USDA (US Department of Agriculture), around 41% of US farmland was operated by farms with sales above $500,000 and the average farm size was 445 acres. For context, almost 64% of European farms are less than 12 acres in size, meaning that an average US farm is more than 30x larger than its European counterpart. South America paints a similar picture to that of the US.

The good news for Deere is that the current trends in agriculture (discussed more in-depth in the following section) are impacting farm consolidation in Europe, meaning this geography might eventually become a key customer for large ag equipment:

Regulations are also putting a strain on farmer resources like herbicides in Europe, so precision ag technologies might also become a good fit soon.

The company commercializes a wide variety of large ag equipment, with the combine probably being the better-known product of all. A combine is used to harvest and looks something like this:

Deere has always focused on covering the E2E equipment needs of any production system. The company used to market its products according to their function (harvest, planting…) but now markets its products according to production systems (for example, corn production):

Farmers tend to go “all-in” with an equipment brand because it simplifies operations. Deere also provides hefty discounts for farmers who purchase entire production systems, making it tough for farmers to say no.

As discussed in the history section, technology, or as Deere calls it, ‘precision agriculture,’ is at the core of the company’s operations; why? Because the company is no longer selling equipment, it’s selling solutions:

You are buying a solution for your farm; you are not buying a piece of equipment anymore.

Source: AGCO expert call

The company has invested quite a bit of money in developing its tech stack, which is by far the most comprehensive in the industry:

Part of this tech stack has been built organically, whereas other parts have been built through targeted acquisitions like Bear Flag Robotics (Autonomy, acquired in 2021) or Blue River (AI and ML, acquired in 2017). What Deere has managed to build is an ecosystem for the farm.

This ecosystem is sold as a win-win proposition, aiming to make farmers more profitable while enabling Deere to reap part of this value add through a per-use and/or subscription-based model. Take, for example, See and Spray.

Thanks to this technology, farmers can enjoy significant savings as it only fertilizes bushels that require fertilizer. Before See and Spray, farmers had to spray all the crops, even if only 20% of the crop needed it. Using less fertilizer can help farmers make significant savings, as fertilizer costs can make up to 30% of variable costs per acre of corn (for context, equipment makes up around 15% of the cost per acre of corn). The best news is that these savings don’t come at the expense of yield, a KPI for farmers.

There are many more features in precision agriculture, most of which I will not discuss for the sake of time. This short video by John Deere describes some of the benefits of applying technology to the farm:

These technologies are distributed progressively, typically by retrofitting them into used equipment. Once adoption rates get to the 70% to 80% milestone, the company makes them standard in all new equipment and hikes the price of this equipment:

When a feature moves into base, the base price moves up with it.

Josh Jepsen, Deere’s CFO

Another exciting application of technology in the farm is the John Deere Operations Center, which allows farmers to “unlock the full power of their farm data.” These are some of its features:

Through the Operations Center, a farmer can check how all its operations are running on their mobile phone. Smooth operations and careful planning are paramount in farming, as most profits are generated in relatively short periods. Reacting slowly to a problem can bring thousands of dollars in losses to farmers. This short video shows how the Operations Center works:

What’s key is that the Operations Center feeds from a very large data set thanks to the company’s installed base. This data is aggregated and then used to help farmers become more profitable:

What if Ted could learn from 40,000 other lifetimes through powerful insights gleaned through the digitalization of the farm.

Deere has started deploying its precision ag technology across its large agricultural equipment, but the goal is to deploy it across most equipment operations segments in due time. The reason why it might have started in precision agriculture is two-fold…

It’s where it can currently add the most value: minor improvements in yield can bring enormous benefits thanks to scale.

It’s where it can collect the most data to improve the technology further: Deere’s installed base in this segment is unprecedented.

There’s no denying that the agriculture industry is transforming from an equipment-based industry to a SaaS-based one, enabling farmers to do more with less. Farmers are embracing technology at a fast clip, although even those who are reluctant will have no choice but to hop onto the trend if they want to remain competitive. Agricultural products are commodities, so farms are price takers, and thus, their production costs determine their profitability.

(b) Small Agriculture and Turf (SAT in short)

The SAT segment specializes in the sale of smaller equipment, and this is important because it somewhat changes the customer base. Deere’s large agricultural equipment has historically targeted large farms specializing in large crops, whereas the small agriculture and turf segment targets…

Individuals or companies who might want this equipment to take care of their backyards

Smaller farms that focus on higher-value crops such as fruits, for example

Golf courses

I will not go through all of the equipment the company sells in this segment, but here’s one of the best sellers, the Gator:

Differences between the PPA and SAT segments stand out when we compare tractor sizes. This is a tractor that Deere sells through its SAT segment:

And this is a tractor that’s sold through its PPA segment:

The differences in size and power are evident just by looking at the images. I wouldn’t say one piece of equipment is better than the other; they are simply different and target different use cases. The second tractor would not be a good fit for a European farm, whereas the first would not have sufficient power for a large US farm.

As the SAT segment targets the retail customer (to an extent), Deere started selling its small agriculture equipment through big box retailers like Home Depot and Lowe’s more than 20 years ago. This is yet another difference with PPA, as most of that segment’s sales take place through the company’s exclusive dealer network.

Despite the stark differences across both segments, it was not until 2021 that Deere separated its former Agriculture and Turf segment into these two. Many things might have led management to make the distinction. The main one is probably the rise of precision ag, which is currently much more suited to large agricultural operations. Another reason might be that these segments’ cycles are very different.

(c) Construction and Forestry (CF in short)

We have learned about Deere’s agricultural segments, but the company also manufactures Construction and Forestry equipment. The company started manufacturing construction equipment in the 1950s to complement its agricultural operations and then solidified its position in this industry by acquiring Wirtgen in 2017. When Deere acquired Wirtgen, it was the leading manufacturer worldwide in the road construction industry. Uncoincidentally, road construction is one of the tasks in construction that’s most prone to automation and something Deere was actively looking for:

The acquisition of the Wirtgen Group gives Deere far greater exposure to transportation infrastructure. This sector that’s faster growing and less cyclical than the broader construction markets today.

Max Guinn, Head of the CF division in 2017

It’s also a market expected to enjoy strong tailwinds going forward, but I’ll talk about this in more detail in the next section.

Deere also provides solutions for large and small projects through its construction division and also aims to provide customers with the equipment necessary to cover the whole construction project:

Lastly, Deere also offers equipment used in forestry applications:

Equipment operations’ distribution

This is how equipment operations are distributed across segments and geographies:

The company is most exposed to Production agriculture and North America. This makes sense because Deere is the undisputable leader in large ag equipment, and North America is much more prone to this type of equipment and is the most mature market.

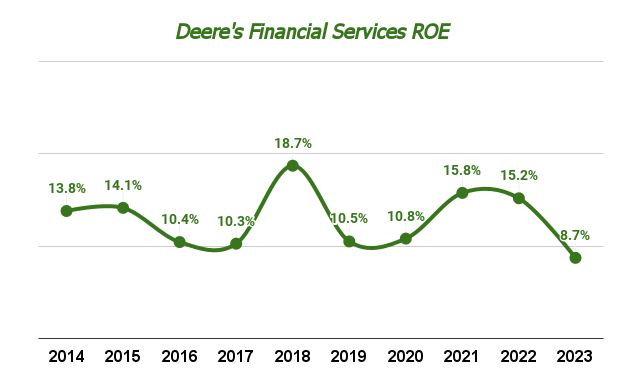

(d) Financial services

The last of the company’s operating segments is its financial services segment. Deere does not aim to maximize profitability in this segment but instead uses it as an enabler of its equipment operations. Despite equipment not making up a large portion of a farmer's total cost, it does require a significant outlay of capital upfront. This is precisely where Deere Financial comes in handy, allowing farmers to smooth out this outlay.

Deere provides financing for two parties:

The dealers that buy the new equipment from Deere

The individuals who buy the equipment from the dealer

There’s not much more to it. Despite the word “financial” sounding scary, I think there are several things that should be reassuring:

It’s not a profit maximization operation. Profit maximization is a key driver of financial fraud.

Deere has been providing financing to its customers and dealers for decades, and financial losses have always been under control, even in downcycles. It’s fair to assume it’s a niche the company knows well.

Deere Financial provides somewhat recurring revenue through downcycles.

In fact, how the company has treated customers through its financial operations has helped it strengthen its moat. You’ll understand why after reading the section on the moat.

So, if we were to summarize Deere’s operations, it would look something like this:

The premium subscription gives you access to all the content in Best Anchor Stocks, which includes…

All the deep dives

Recurring articles

Access to my real-time portfolio and transactions

Occasional webinars on various topics

A community of like-minded investors

A subscription the Premium + also gets you a quarterly Q&A with me to discuss anything you’d like.

If you want to know the type of content I share at Best Anchor Stocks you can read the Deere deep dive I uploaded a few weeks ago for free…

…or you can also read any of the other many free articles I have shared, just like this one!

You can also read the testimonials that existing subscribers have left. If you are a passionate and curious investor wanting to learn about high-quality companies, don’t hesitate to join Best Anchor Stocks!

Section 2: The Financials and Growth Drivers

I’ll discuss the company’s financials and growth drivers in this section. One of the best things about Deere is that its reported financials are somewhat misleading, which might make many ignore the company from the get go. I must admit I was close to being one of these people, but I fortunately decided to dig deeper.

The Financials

I will review the company’s three most important financial statements: the income statement, the balance sheet, and the cash flow statement. Context is required for all of these because they each have their puts and takes, although they have one thing in common: they tend to be volatile through the cycle (especially the income and cash flow statements). For this reason, I will share a snapshot of the company’s 2023 numbers and some historical data going back to 2013, the prior peak of the agricultural cycle. This way, you’ll be able to understand the cycle’s impact.

While I do believe Deere will be cyclical in the future, I think there are caveats: I don’t think the future will look exactly like the past. I believe Deere is becoming a better business by transitioning to a more recurring revenue model, which should translate into lower financial variability going forward:

What’s unique about this time and a little bit different is some of the business model changes that we have; it’s going to allow us to take some of the standard deviation around that 20% out.

By reading this section, you’ll also understand why many investors disregard Deere as an investment. Very few (if any) financial providers manage to dissect the company’s financial statements accurately. Deere has two very differentiated segments: equipment operations and financial services. The characteristics of both are very different and thus should be viewed independently. Looking at Deere on a consolidated basis might make us reach the wrong conclusions.

The income statement

Deere’s 2023 consolidated income statement looks something like this:

This table paints a static picture but already brings several interesting insights. First, we can see that Deere enjoys excellent margins, mainly achieved at the operating level. The company has a “lowish” gross margin due to the nature of the equipment-selling business, but it later manages to pass a good portion of this margin through to the bottom line, enjoying a net income margin of almost 17%. This income statement is somewhat similar to Copart’s income statement, where the most significant cost burden is buried in the ‘cost of revenue’ line.

The second thing is that Deere includes interest expenses as an operating expense. This makes sense because this interest comes primarily (not all) from its financial services segment, which generates income included in its consolidated revenue line. Deere’s Financial Services segment works like a bank, and interest expenses are considered operating costs for financial firms because they are intrinsically linked to the business. Note that, as discussed above, Deere does not aim to maximize profitability in its Financial Services segment, so why do we tend to see some kind of variability in the spread of interest income and expenses? The reason lies in interest rate movements. As per the company’s annual report:

Historically, rising interest rates impact our borrowings sooner than the benefit is realized from the financing receivable and equipment on operating lease portfolios.

All this said, the above income statement might not be entirely representative of the company’s normalized earnings power. Deere is a cyclical business, which, when coupled with a high fixed-cost base structure, makes the company suffer from operating leverage/deleverage. If we look at the period from 2013 to 2023 (peak to peak), we can see this operating leverage/deleverage in play:

Note how margins peaked in 2013, only to fall quickly once the downturn began until bottoming in 2016. Management tends to make some adjustments to prepare for downturns, but there’s so much one can do when running a manufacturing business. There are two good news, though.

First, the company remained profitable (and by no small margin) during the last downturn. Secondly, management focused its adjustments more on SG&A than on R&D. This is key because R&D is crucial for the company’s future, and management has repeatedly stated that their willingness to cut back aggressively on these costs is low. This willingness has been low for a pretty long time:

John Lawson was with the company for 44 years and never remembers a time anyone suggested cutting back on research and development spending, even in the toughest times.

Source: ‘The John Deere Way’

Management knows that cycles are temporary but that the competitive position is permanent. Remaining profitable through the cycle obviously facilitates this countercyclical behavior.

What’s pretty evident is that the company has enjoyed operating leverage over the long term, leading to better margins through the cycle (note that Finchat does not include interest expense as an operating expense for Deere, which is why you see higher margins in the graph below, but is the trend that I am interested in, not the numbers per se):

This operating leverage has been quite pronounced over the last couple of years, and there might be several reasons to explain this. The first one is that a good portion of the growth generated over the last years has come from price increases. Price increases do not come with a comparable capacity surge and thus help the company enjoy operating leverage. The second reason might be related to Deere’s focus on subscriptions and parts. These ventures enjoy significantly higher margins and are more scalable, so they obviously come with considerable operating leverage.

As cycles inevitably bring margin volatility, management sets expectations of operating margins through the cycle. The current expectations are set at 15%, but management expects to achieve 20% through the cycle operating margins in the foreseeable future. This obviously makes sense as technology, subscriptions, and parts revenue grow faster than overall equipment revenue. Not only are these higher-margin revenue sources, but they are also more recurring, taking away a portion of the volatility. High recurrence and profitability are precisely the characteristics that make software and parts companies great, and that’s where Deere wants to transition.

Don’t forget that management targets around 10% subscription revenue in 2030, which should help take the recurring piece of the business to around 40% of total revenue. We don’t have disclosures to understand how this number looked in the past or even what it looks like today, but that would probably be the highest in history. Also, note that this 40% number is a sales ratio and what we should care about is profits. With recurring sales carrying significantly higher margins than equipment sales, I think it’s conservative to see a path to 60%+ of recurring profits.

Maybe an underappreciated part of the company’s margin story that makes it more credible is that every other competitor is also looking to expand margins following a similar model, meaning farmers will have little choice but to adapt to the new model.

All in all, Deere’s income statement is currently in good shape, has continuously improved through cycles, and is transitioning to more recurring and higher-margin revenue. This doesn’t mean it will improve linearly from here, though. With a potential downcycle on the horizon, we might see it worsen significantly next year. However, this should not matter much if we focus on the long term.

You might have noticed that I did not separate the equipment operations segment from financial services when reviewing the income statement. The reason is that including the interest expense as an operating expense should give us a somewhat normalized picture.

The cash flow statement

As you might well know, we should care about cash profits rather than accounting profits. Accounting rules do a somewhat good job of portraying a company’s economic reality, but management teams can typically tweak them through their assumptions to make them look better than they are. This can also be done with cash flow, but to a lesser extent.

One of the first things I look at in any company is its cash conversion. There are many ways to calculate this metric, but I usually take Operating Cash Flow and divide it by Net Income. You can also take Operating Income, but recall that, for Deere, you must include interest expense when calculating operating income.

If cash conversion is close to 100% or above, then great; if it’s significantly lower, we must ask ourselves why this is the case (it might simply be the nature of the business). Let’s see how cash conversion looks for Deere. I have built two tables, one with the equipment operations business and the other with consolidated figures. This way, we’ll understand both individually. I also included two periods, the last three years and from 2013 to 2016. This way, we can see how cash conversion varies through the cycle. This is equipment operations:

As you can see from this table, Deere enjoys good cash conversion in its equipment operations segments. What’s most interesting is that this cash conversion does not tend to worsen materially during downturns. The other interesting thing that I’d point out is that the company has significant Capex flexibility. When it entered the 2015 downturn, Capex dropped from 3.2% of sales to 2.6% despite a significantly lower sales level. This flexibility obviously helps the company’s free cash flow conversion remain resilient.

However, the above is not the whole story. Deere receives distributed earnings from its financial services subsidiary but doesn’t record the rest of that business’ cash flows in its equipment operations. This makes this segment’s cash conversion numbers look somewhat misleading, so we must look at the consolidated figures. Here they are:

The consolidated cash conversion figures look worse but still pretty acceptable. For the last 3 years, Deere has converted, on average, 80 cents to cash for every dollar of net income, not bad. We must not forget Deere is a manufacturing business, meaning it’s tough to get to a Free Cash Flow conversion rate close to or above 100%. The company not only carries inventory but also requires Capex to build manufacturing capacity. The good news is that, as I discussed above, the company can adjust Capex accordingly when a downturn begins, meaning Capex is somewhat a variable cost.

Another thing worth noting, which I will discuss in more detail later, is that Deere can significantly improve its cash conversion by successfully executing its current business strategy. This said, I think cash conversion is at an acceptable level currently and will be resilient during the next downturn due to Capex's flexibility and because management claimed the company’s inventory position is at the best level it has ever been. Management is even guiding for an improvement in cash conversion in FY 2024 despite the expected sales and earnings drop.

The balance sheet

One of the most interesting things about Deere is its apparently high debt load. When I come across a new company that might be interesting, I tend to run it through a series of parameters (a quantitative checklist) to see if it gets me more or less convinced to dig deeper. The first thing that stood out when running Deere through these parameters was its net debt position. According to several financial providers, the company ended 2023 with a net debt of around $59 billion. This amount is pretty significant for a company of Deere’s size (around $110 billion market cap).

However, this number is extremely misleading for several reasons. The reason that stands out the most is that a good chunk of this debt belongs in the financial services segment. Debt is necessary for any financial business to generate adequate returns, and Deere’s Financial Services Segment would not be different. The good news for those investors willing to read the full annual report is that Deere dissects both balance sheets, and thus, we can calculate the real indebtedness of the equipment operations business.

Deere ended 2023 with borrowings (both short and long-term) of $56 billion, but only $8.44 billion of this amount could be attributed to the equipment operations segment, the remainder being attributable to financial services. You can find this highlighted in the table below:

The equipment operations segment also has $5.7 billion in cash and equivalents, yielding a net debt position of $2.74 billion. If we compare this with the segment’s operating income of $12.2 billion, we get to a net debt/EBIT ratio of 0.22x, which is pretty conservative if you ask me. Several caveats here, though. First, this ratio will probably increase during a downturn due to lower operating income. That’s the “bad” part. The good part is that as the company transitions to a more recurring model, its financial position strengthens even if this ratio does not change.

Now that we know that Deere’s equipment operations segment is not as highly indebted as it might look at first, let me comment on its financial services segment. There’s no denying that financial services runs with high leverage; it’s a financial business, and leverage is a “requirement” to obtain acceptable returns. We also know financial businesses tend to get into significant trouble due to this leverage when things turn south occasionally (the Global Financial Crisis is a good example). Am I not worried about Deere following a similar path? The answer is “no,” and for several reasons.

First, the company has been operating in this niche for almost two centuries, and we could argue it knows its customers (both farmers and dealers) well. It’s reasonable to think that risk is under control in this sense. Looking back, we can see that the company’s loss provisions have never spiraled out of control, not even during harsh downturns. This makes sense, considering Deere understands the cycles, farmer economics, etc. To this, we have to add that equipment costs typically make up around 15% of farmers' total costs, so they have other places where they can try to save money, places where Deere is trying to help them save money.

Secondly, Deere uses its financial services segment as an enabler of its main business, not as a profit-maximization operation. Leverage does not create problems when run conservatively but when run too optimistically/aggressively, which tends to happen when someone tries to maximize their profit.

Lastly, but not less importantly, most of Deere’s debt is backed up by its equipment, which typically carries a high residual value. If some customer defaults (something inevitable), Deere gets the equipment and can resell it to recover some of the outstanding amount. This is from the book I shared before:

If John Deere Credit had to collect on a default loan in the agriculture industry, the collateral - a John Deere tractor or combine - was a known and valuable piece of equipment, even used.

I don’t think Deere is risky despite the leverage in its financial services segment for the reasons discussed, and I must say I am not alone here. Most CRAs (Credit Rating Agencies) believe the company is in a pretty good financial shape (I know, I know, these are the same CRAs that messed up during the GFC):

Note that it’s in Deere’s interest to maintain such a financial position, as it ultimately gives the company access to cheap financing, which it then uses to finance dealers and customers and, thus, sell equipment.

All in all, I hope this section has helped you understand why Deere’s financials are much better than they appear at first glance. I was close to rejecting the company just based on numbers I got from some financial providers that don’t distinguish between the company’s financial branch and its equipment operations. Luckily, I decided to dig deeper after reading the book about its history. Lesson learned!

The Growth Drivers

Growth is an essential consideration for any investor unless one is buying stocks at a FCF yield of 12%+. In that case, an investor should worry more about the resilience of that FCF than about growth. However, this is not the case for Deere as it’s currently trading at a FCF yield of 5.5% (Next Twelve Months based on management’s guidance). This means that to achieve a market-beating return, we, as investors, are expecting some Free Cash Flow growth over the coming years.

The question is: where will this growth come from? There are four sources of free cash flow growth: revenue, margins, cash conversion, and capital intensity. Let me discuss each individually.

Revenue growth

Deere enjoys several long-term secular top-line growth drivers. First, let's see where we come from. Deere has managed to grow its revenue at a 5% CAGR over the last decade. This is very acceptable, considering the company was at a peak in 2013, and the industries it’s exposed to typically grow in line with GDP. But why will this growth continue going forward?

First, the agriculture industry will benefit from several growth drivers, one of which is population growth. The world population keeps growing, and emerging markets increasingly consume higher protein foods which come from animals that must be fed grain. This means the need for food is increasing, which obviously positively impacts the agriculture industry. The industry has two ways to meet these needs:

Use more land

Make the land more productive

Land availability in places where the weather supports agricultural practices is diminishing, so it’s highly likely that farms will need to lean increasingly on #2. Technology will be key to this increased productivity, which Deere is already actively deploying across its fleet. This technology will be sold as a win-win proposition as it will add value for the farmer while Deere captures some of this value add. This value add evidently comes from helping farmers lower their cost base:

On an acre of corn, nitrogen and fertilizer represented about 35% of the variable cost structure and about 75% of the greenhouse gas footprint.

Management has sized this value add opportunity at $150 billion, of which they plan to take around 25%:

This means the potential revenue for the company is $37.5 billion ($150 billion * 25%), revenue which would come at a pretty high margin due to its nature. Now, I will not take management’s word at face value, less so when we are talking about TAM, but I think it’s pretty clear that the opportunity is very significant even if one decides to be more conservative. Note also that competitors expect to be more aggressive in taking value-added share, which might benefit Deere’s value proposition. AGCO’s management recently mentioned they expect to take half of their value-add, 100% more than Deere.

Farmers will have no choice but to adapt to the new model even if they are initially reticent due to regulation and competitiveness. Regulators are increasingly pushing farmers to be more productive with less inputs, and technology will play an essential role in this “more with less” trend. Secondly, if other farmers deploy technology, then farmers that don’t will become less competitive, which will eventually lead all farmers to make the transition. This is how John May, Deere’s CEO, laid it out during the most recent investor day:

The days of abundant resources and farming inputs is over. Labor, fertilizer and crop protection inputs, just to name a few, are all growing in scarcity and they’re increasing in cost.

Technology also brings interesting dynamics to the industry. For example, data is very important for farmers because it allows them to improve yields. This data is most useful when consolidated and used across homogeneous equipment, meaning that going all-green might be a case not only of brand loyalty but also of productivity. Network effects might come into play in an industry where they have historically been absent.

Deere’s construction segment is also expected to enjoy significant tailwinds. In 2021, the US government passed the Infrastructure Act to fund US infrastructure. This Act received bipartisan support, which is a testament to its importance. Deere will benefit to an extent from these investments, especially from the construction of roads and bridges ($110 billion) due to Wirtgen's leadership in road construction. Quantifying its impact is tough, but it will definitely be a tailwind.

Also, note that there’s onshoring going on right now after COVID and geopolitical conflicts wrecked chaos across the supply chains. Many companies have decided to establish all or a portion of their supply chains on domestic soil, and Governments are incentivizing this onshoring (the Chips Act is a good example). These mega projects require considerable construction efforts and constitute another business tailwind. I must say that I think this trend will be quite relevant in the future, which is why I am looking at companies that might directly benefit from it. Deere will definitely benefit, but more so indirectly.

All in all, I think the company’s top-line growth will not be a problem going forward, as there will be significant growth opportunities available.

Margin expansion

This section is much simpler to explain: Deere’s margins should expand as it transitions to more recurring and higher-margin revenue. Management expects around 40% of recurring revenue in 2030, with 10% being subscription-based. This, of course, has led them to claim the company can now achieve a 20% margin through the cycle, an unprecedented level in its history.

Improved cash conversion

Margins are not the only place where the transition will prove beneficial; cash conversion is another one. Subscription-based businesses enjoy negative working capital (which is like free financing) because they get paid at the start of the year, and Deere should also benefit from this characteristic once the transition is more mature. Additionally, as equipment sales become less important to revenue (albeit continuing to be critical), cash conversion should also improve thanks to inventory making up a lower portion of the company’s cash conversion.

Lower capital intensity

Free Cash Flow is normally calculated as Operating Cash Flow minus Capex, meaning that we should not only care about the former but also about the company’s capital expenditures. I think the conclusion here is straightforward too: capital intensity should naturally decrease as the equipment sales per se make up a less significant portion of overall sales. The reason is that the recurring revenue the company expects to generate requires little capacity expansion, or put similarly, it’s capex light.

I don’t anticipate Deere will look like a software business in the coming years, but the transition to a more software-like model should undoubtedly improve the company’s margin and cash conversion profile. To this, we have to add that growing the top line is unlikely to be a challenge for Deere over the long term.

With the company trading at a 5.5% FCF yield at mid-cycle (according to management), we “only” need around 5-7% FCF growth to make this a worthwhile investment (as this would get us to a return of around 10-12%). I think this will most likely prove to be conservative, but we can only wait and see.

Section 3: Competition, moat, and risks

This section will discuss three topics that are very relevant to any company: the competition, the moat, and the risks. Of course, the relevance of these topics depends on ones investment horizon, as I highly doubt someone willing to hold a company for months should really care about these.

The Competition

This section on competition can only be fully understood once you’ve read the next section on the moat. I can give you an overview of the competitive environment here, but you’ll only truly grasp Deere’s competitive position when you understand what protects it against other players. Let’s start with agriculture.

The competitive landscape in agriculture

The agricultural equipment industry is pretty consolidated across the large players, with the top 5 gathering a combined market share of 64%. The industry has historically enjoyed high barriers to entry because a new entrant needs expertise, the money to spend on Capex, and the dealer base to service and sell their equipment. These three things have been progressively built by the existing players not only with abundant amounts of capital but also with time. We should also remember that the equipment per se is somewhat a commodity, so it would be extremely tough to convince farmers to switch to a new piece of equipment unless it’s significantly better. As you’ll see later on in the section on the moat, even this would probably not be enough to justify a switch.

Deere is by far the largest company in the industry, commanding a 25% global market share. CNH is the company’s closest competitor, but its market share is not even half that of Deere’s. Other relevant players are Kubota and AGCO, which are much closer to CNH. The bottom line is that there’s one outlier, and that’s Deere:

We should not, however, take this market share data at face value. It’s a global number encompassing all agricultural equipment, but it requires context because market shares vary significantly across geographies and product types. For example, Deere has a considerably larger market share in the US, commanding 40% of the agricultural equipment market. On the other hand, AGCO, through its Fendt brand, is much more dominant in Europe than in the US. Something similar happens to CNH through its brand, New Holland. Deere also leads the European market, but by a thinner margin than the US.

This divergence in market shares not only makes sense due to Deere’s origins (US) and focus but also due to the characteristics of US farms. As discussed in another section, farms in North America are much larger than elsewhere and, thus, more tailored to large agricultural equipment, where Deere is the indisputable leader thanks to its long-time investments (remember the “New Generation of Power” event?).

The competitive landscape across other geographies is different. Although I will not go over them individually, they all have one commonality: Deere seems to be an established player everywhere but does not enjoy a competitive position as strong as that in the US. Other geographies seem more competitive, sometimes due to their relative youth and others because small agricultural equipment is dominant. For example, Deere has a market share of around 9% in India, whereas Mahindra dominates the industry with a 40%+ market share.

If we look at equipment types, we can see that Kubota is a pretty strong player in the small ag equipment niche. In fact, the company does not even try to manufacture large ag equipment (other manufacturers do). The company’s largest tractor has a power between 130 - 170 HP,

This pales compared to Deere’s largest tractor, which has between 484 and 913 HP.

This doesn’t make Kubota a bad company (we’ll see later on in the risks section why it can do great in the future). Kubota has simply focused on a niche where Deere is not as established. There are also differences between market shares of any given piece of equipment. For example, Deere is famous for its combines where it has an even greater market share in the US than its overall US market share:

So, what do these companies compete on? Or better said, what drives a farmer’s purchase decision? Agricultural equipment is somewhat commoditized, so farmers ultimately care about the cost of ownership, which is not the same as price. If any given piece of equipment is more productive than another, its purchase might make sense even if it’s more expensive.

So, what variables go into the total cost of ownership? Many… things like price, productivity, and downtime…but what I want to stress is that it’s not a decision based solely on price. As I’ll explain later in the section about the moat, several things should allow Deere to protect its market share and grow it going forward; none of them are related to the price of its equipment. In fact, there are reasons to believe that the industry dynamics will start favoring the large players much more than they have in the past.

Competition in construction equipment

I’ll be brief here because it makes up a smaller portion of Deere’s total sales. Caterpillar and Komatsu dominate the construction equipment industry, with market shares of 16% and 10%, respectively. Deere has a decent size but comes in at a 5% market share, which is significantly lower than the leading operators:

Interestingly, the construction industry is more fragmented than the agriculture industry. The top 5 agricultural players comprise around 64% of the market, whereas the top 5 in construction comprise 43% of the industry. This might be related to various factors I’ll discuss in more depth throughout the article. For example, farming is known for being a family-run industry, whereas this is not the case for construction (or at least not to the same extent). It also seems easier to differentiate a piece of equipment in agriculture than in construction because many more inputs are going into agriculture, which the equipment can directly influence.

So, Deere has a respectable market share in the construction industry but not an outstanding one. The only caveat here is that, as I discussed in another section, Deere has managed to carve a leadership position in a niche in the construction industry thanks to the Wirtgen acquisition: road building. I could not find specific and/or updated numbers, but I did find this article that shared Wirtgen’s market share in 2016:

Worldwide, in the milling business, they have a 72% market share. They are number one by far, and for number two you will see a single digit. For the pavers, it is 37% market share worldwide, and for rollers it is 19% market share worldwide.

These numbers might have changed over the past years, although judging by recent news, the competition seems to be having quite a bit of trouble going after Wirtgen’s dominance in road building:

As discussed several times throughout the article, road building enjoys several secular tailwinds, especially in the US, where a good portion of the Infrastructure Bill will be destined to construct roads and bridges.

All in all, I believe Deere enjoys a solid competitive position in both the agricultural and construction industries. It’s definitely much stronger in the former, but we should not discount it in the latter, especially in road building, thanks to Wirtgen.

The moat

A solid current competitive position is of utmost importance but how the company protects it over the years is arguably much more critical. This is where the moat comes in.

I believe there are several prongs to Deere’s moat, most of which stem from the company’s historical industry leadership. Many investors will claim that the past is not important to invest, but I put a lot of weight on it during my research process, and Deere is a good example.

The installed base

Deere has operated in the agricultural industry for over 180 years and has led the industry for a good portion of those years. The company passed International Harvester in 1963 as the leading manufacturer of farm and industrial tractors and has never looked back. That’s 61 years leading the industry.

So many years of leading the industry have allowed Deere to build an extensive installed base and brand. This brand has grown and endured through generations, making farmers very loyal to Deere. Let’s not forget that farms in the US tend to be family-owned, meaning that the brand tends to rollover from one generation to the next:

97 percent of all U.S. farms are family-owned, and family farms account for 90 percent of all farm production by value.

I’d imagine that if the farmer’s son or daughter has grown up operating Deere equipment, the probability of them switching once they run the farm is relatively low. This brand reputation is a real competitive advantage (discussed later), but it’s hard to justify as durable. Brands come and go, and the agricultural equipment industry is fairly competitive, so how will Deere turn its installed base and leadership position into a durable competitive advantage? The answer lies in technology and scale.

Let’s talk about technology first. As discussed throughout this deep dive, the agricultural industry is transitioning to a price-to-value model thanks to technology. Equipment manufacturers will aim to unlock a win-win proposition (both for farmers and equipment manufacturers) by applying technology to farming operations. As we’ve seen play out in many other industries, the better the technology, the more value it will add.

Data is crucial to improving any technological application, and that’s precisely what Deere has plenty of: data. Deere currently has more than 340 million engaged acres (reflects the number of unique acres with at least one operation pass documented in the Operations Center in the past 12 months) and expects to expand to over 500 million in the coming years. This expansion will be driven by the company’s ambition to have 1.5 million connected machines.

Engaged acres are important because they are constantly generating data that Deere can then feed its algorithms to develop the best technology. This improved technology adds more value for farmers, so Deere’s differentiation improves. As I commented above, farmers sell a commodity, so cost is paramount. This means that if Deere owns the equipment that provides the best ROI (Return on Investment), then farmers will have no choice but to switch (if they are not Deere customers) or renew their equipment (if they are existing customers) to remain competitive. These dynamics should further increase the company’s installed base, powering its data advantage. It’s a flywheel that works something like this:

Management described this flywheel pretty succinctly during its most recent investor day:

We have in agriculture a significantly larger installed base. This allows us to collect a larger database that allows us to make our products better, deliver more value to the customers, keep improving them, and develop new products and solutions faster. This is a flywheel that we’re able to keep turning and make our products better, and the more we make our products better the more customers we attract, which feeds back into more customers and better models.

Operating models with technology as a foundation have historically resulted in “winner-take-all” dynamics, and I don’t see why it would be any different here. The largest player in the agricultural industry (Deere) will most likely use its larger footprint to develop the best technology, strengthening its competitive position. Note that this is not exactly the same case as software because hardware is a critical piece in agriculture. This hardware collects the data, meaning the technology is more challenging to disrupt unless you can match the physical presence.

Note that despite these dynamics, I don’t believe Deere will take all of the market. I do believe, though, that the interplay between the largest installed base and the best technology will strengthen Deere’s moat and probably increase its market share.

The dealer base

Deere markets its products through its exclusive dealer base. These dealers buy the equipment from Deere and later “resell” it to farmers or construction customers. Dealers are not only in charge of reselling this equipment but also of building (and maintaining) customer relationships and servicing the equipment throughout its lifecycle. This should already indicate that dealers are a crucial part of Deere’s value chain and also an integral part of its moat.

Service in the agricultural industry is vital because farmers make most of their profits during relatively short periods. This fear of “downtime” is why the dealer infrastructure to keep the equipment up and running is so critical. Deere currently has around 2,156 dealer locations across pretty much every US state:

The company has incentivized dealers to concentrate over the last couple of years. This concentration has two beneficial impacts:

The dealer base becomes more efficient and professional

The financial risk for Deere is lowered because the financial health of dealers improves

Their (Deere) dealers are unprecedented, number one. They did that starting in 1965- 1995. Now, they continued phase two of that is consolidating those dealerships and reducing the number of corporate owners.

Today, in the big equipment, the average John Deere dealer has 16 locations. That makes them more efficient to operate. They can spread costs. They have efficiencies. I'm very envious of Deere.

Source: Expert Call

The company’s dealer base is by far the largest in the US and one of the primary reasons it has remained the leader for so long. The longevity of this dealer base has also been key, as farmers have had relationships with these for decades. I anticipate dealers will play a key role in enabling Deere’s transition to more recurring revenue sources, as they’ll be ultimately responsible for selling those services.

Just so you can grasp what kind of competitive advantage the dealer base brings, take a look at what an expert said about AGCO, its products, and its penetration in North America:

The Fendt tractor is an awesome tractor. It's very well built, typical German engineering. Its acceptance in North America is moderate. I think a lot of their issues in North America is they just don't have the dealer base to service those things.

There’s much more to a buying decision than the product; it all comes back to the dealer, and Deere clearly leads with its footprint:

I think the biggest thing that people need to, it's even something for people in the business, the mentality of the farmer, the buying decisions. I've seen this firsthand, so I'm going to speak. They'll look at a product. They'll sit in a tractor. They'll drive this tractor. They may say, "This is literally the best tractor I've ever sat in. This is the best tractor I've used." They will make those comments. You sit there and go, "Great, how many are you going to buy?" They go, "No, I'll never buy this tractor because I have a dealer that I deal with. That guy has been really good to me and my father before that. I'm a red guy, or I'm a green guy.

Source: Expert Call

So, how can competitors build a similar footprint? It’s tough, mainly because Deere’s dealers have very little to no incentive to switch brands:

The conversions of a John Deere dealer making a change to another brand, that has to be done with a lot of thought and a big consideration. For the most part, the major machines are commodities. A sprayer sprays, a planter plants, and a harvester harvests. Now, it's down to my dealer choice.

Source: Expert Call

Deere’s dealers enjoy the most significant volume and the best margins, so switching to another brand would require something substantial. The only incentive would be if other brands manufactured equipment vastly superior to that of Deere, which not only doesn’t seem to be the case but might also become less likely over the coming years for the above reasons.

Scale

Thanks to outstanding execution throughout many decades, Deere has gathered significant scale. This scale is also essential because it allows the company to enjoy significantly higher margins than its competitors while outspending these on R&D to build its tech stack. In short, Deere can spend more than its competitors on R&D while remaining more profitable (this is probably the reason why many big tech companies have remained dominant for so long).

Let’s look at some numbers. For example, Deere spends 20 basis points less of its sales on R&D than AGCO, but spends almost 4 times more on an absolute basis:

As the flywheel I have discussed above comes into play, this scale advantage should only expand because the industry should favor “winner-take-all” dynamics. The companies’ operating margins evidence this scale advantage:

Higher profitability is important because, if there’s a downcycle, Deere has much more flexibility to continue investing in R&D than its competitors, who might look to cut expenses there to remain profitable. We also see that scale and higher profitability can make a difference for Deere regarding the share of value-added value its competitors intend to take. AGCO wants to take 50% of their value-add, which is pretty aggressive compared to Deere’s 25% cut. Of course, Deere is in a position to take less because it does not “need it” as much as AGCO. This ability to be less aggressive might strengthen Deere’s value proposition relative to AGCO’s.

(Brief note: AGCO is a company focused entirely on agriculture, whereas Deere is not due to its construction and forestry operations. This makes the comparison slightly misleading, but the message still applies.)

Brand reputation

At the beginning of this section, I mentioned that I don’t consider brand reputation a strong competitive advantage for any company because brands can go out of favor eventually. This claim, of course, is nuanced. For example, I’d say the above is definitely true in retail, where customers tend to be fickle. On the other hand, the brand might be much more important in the luxury or ratings industries, where they typically carry a greater meaning. In luxury, that would be heritage, whereas, in ratings, that might be trust. But what about Deere? I don’t think Deere is comparable to luxury or ratings regarding brand reputation, but I believe it matters more than for any given retail company. Deere stands somewhere in between both groups.

The reason stems from farming being a family-based industry. Many farmers have been operating Deere equipment for many decades, which is important not only because they have gotten used to it but also because the company has historically been there for them when things got rough. This is from the book ‘The John Deere Way’:

Many John Deere customers are still loyal to the company because their families were able to keep their land and farms during the Depression because of the company (Deere).

We should not underestimate the importance of this loyalty in a market where 97% of farms are family-owned. This brand loyalty does not avoid disruption risks but mitigates them significantly. Farmers currently loyal to Deere must find a good reason to switch to a competitor, especially when such a competitor does not strongly differentiate against Deere.

The risks

I believe Deere is a wonderful company, but it’s not risk-free. Let’s review some of its most significant risks.

Unions

The most relevant risk for Deere probably comes from labor unions, although I believe this risk will diminish over time. In case you don’t know, labor unions are organizations that help workers achieve better conditions in their respective workplaces or, maybe better said, that help them avoid unfair working conditions. It’s very typical to see unions involved in manufacturing businesses because these tend to be labor intensive, and labor tends to be somewhat of a “low-value add” in such businesses. In short, where a lot of labor is required and the labor supply is large, you tend to find more unfair working conditions.

Management notes in the annual report that around “80% of production and maintenance employees are unionized.” This already seems pretty significant by itself, but it becomes even more important considering these unions have been active lately.

Deere suffered a strike in 2021 that negatively impacted its operations (as all strikes do because that’s the main goal). The strike was organized by UAW (United Auto Workers) and was the company’s first in over thirty years. UAW might sound familiar because the union wreaked havoc across the automobile industry in 2023 by organizing three separate strikes at General Motors, Stellantis, and Ford.

In Deere’s case, the strike involved around 10,000 of the company’s workers and lasted around 5 weeks until workers signed a new labor agreement. This labor agreement obviously came at a cost for Deere, which will see increased labor costs over the coming years. This is a summary of the terms of the new agreement:

Both included a 10% immediate raise, an $8,500 signing bonus, additional 5% raises in the third and fifth year of the proposed six-year deal, and additional lump sum payments equal to 3% of pay in years two, four and six. In addition it restored a cost-of-living adjustment to protect workers from increases in consumer prices. Such clauses used to be common in union contracts but have become relatively rare in recent years.

Source: CNN Business

Josh Jepsen, Deere’s CFO, quantified these costs in a relatively recent earnings call:

Over the 6-year contract, the incremental cost will be between $250 million and $300 million pretax per year with 80% of that impacting operating margins.

This is undoubtedly a significant amount, but I think there’s something even more “dangerous”: the strike sets a dangerous precedent as other unions might ask for better terms in the coming years. With other labor agreements expiring between 2024 and 2027, we might see more strikes lead to one of the following or probably both:

Disruptions in the company’s operations

Increased labor costs going forward

“Luckily” for the company, the 2021 strike came when the entire industry was suffering a supply crunch. This supply crunch eventually led to a favorable pricing environment that somewhat mitigated the company’s reliance on volume, which is evidently the variable most impacted by a strike. The strike was not really that noticeable in the company’s financials:

The good news is that this risk should somewhat diminish going forward. First, we have to consider the rise of automation. Manufacturing processes are getting increasingly automated, making them less reliant on labor. In my opinion, continuous strikes only increase the willingness of such businesses to invest in technology (Amazon is another good example here). This, by the way, doesn’t mean that some strikes aren’t justified.

Secondly, and maybe less straightforward, Deere’s transition to more recurring revenue sources like technology should also insulate it more from this risk in the future. If a larger portion of profits comes from ventures that are not labor intensive, then the potential impact of strikes on profits decreases.

Competition: A shift to smaller equipment and emerging markets

I have already discussed competition in this article, and the conclusion you should’ve come away with is that Deere is the leading player in the agricultural industry. This doesn’t mean there are no competitive risks; I believe there are a couple we should be very aware of.

The first one is that autonomy might make the industry shift to smaller equipment. While researching the company, I came across several experts who claimed that autonomy might reduce the need for large equipment, and I think their argument makes sense. The agricultural industry in the US has historically transitioned to larger equipment because it has always been labor-constrained. These labor constraints ultimately meant farmers needed to plant or harvest with the least iterations possible to optimize their labor. Large equipment solved this problem.

With the arrival of autonomy, the landscape might change because farmers will supposedly be able to do these tasks with less labor, meaning that the importance of the number of iterations diminishes. For example, a farmer might be able to leave a combine working at night and will not care if the combine takes 3 or 4 iterations to do its job so long as it doesn’t require labor.

The argument makes a lot of sense, but I am skeptical about the transition’s success unless owning smaller equipment is much more profitable than owning large equipment. Farmers are pretty intelligent and focus on profitability, so I highly doubt they will switch unless they see strong evidence that it’s better. If this shift were to happen eventually, I would say Kubota (a Deere competitor publicly traded in Japan) might benefit materially. The reason is that Kubota is one of the leading manufacturers of small agricultural equipment. It’s a smaller company than Deere, but if we were to look at Deere’s SAT revenue (Small Agriculture and Turf), we would see that it’s actually smaller than Kubota in this segment. I would, however, be careful making such a comparison because there might be some product overlap between Kubota and Deere’s large ag equipment:

That said, I don’t see any reason why Deere can’t also dominate this market if it chooses to focus on it. The company has developed the industry's most comprehensive tech stack (which should technically lead this transition) and has decades-long relationships with US farmers.

The other competitive risk comes from emerging markets. Deere is the leading agricultural equipment player in the US and many international countries, but the markets where it dominates tend to be more mature. Emerging markets are less mature and, therefore, tend to be more competitive. Countries such as Brazil, India, or China are considered growth markets in the agricultural industry, and while Deere has exposure to these, they are much less consolidated. I don’t think Deere completely relies on this growth to succeed due to its price-to-value strategy, but I do think it’s something to monitor.

What’s pretty obvious is that Deere is the global leader in agricultural equipment, which means that every other company is “coming for Deere.” Complacency is the real risk here, something that’s always the case for companies that have been leading for so long.

Right to repair complaint

The last, but no less important, risk is related to a letter of complaint that a group of farmers sent to the FTC (Federal Trade Commission). According to some farmers, Deere and other companies in the industry are unfairly blocking them and other third parties from servicing the equipment. They believe this constitutes anticompetitive behavior and want the FTC to intervene to make manufacturers comply with the right-to-repair principle:

The right to repair is the notion that consumers should have the right to repair their lawfully purchased products directly, or by selecting a repair service of their choice, as opposed to returning to the manufacturer or manufacturer-approved providers for the repair.

Source: WIPO

It’s interesting because the complaint does not come from price per se (which tends to be the main reason) but from service levels. Farmers claim that Deere’s dealers are becoming slower in servicing their equipment, which is very important in a business where most of the profit is generated in a relatively short period.

According to Deere, there’s no good argument behind the complaint because the farmers can still conduct around 98% of the repairs. The repairs the farmers can’t do (again, according to the company) require some sort of software update or modification. The reason why farmers are not allowed to conduct these is because such repairs can potentially make the equipment non-compliant with existing environmental regulations.