The Great (Oral) GLP-1 Scare

Why the Stevanato narrative is flawed

This is not something that should take you by surprise because I’ve talked about it in the past, but Stevanato’s stock has been weak lately (maybe an understatement):

This has happened despite the company (imho) receiving incrementally positive news over the past few months. In a recent NOTW, I shared what I believed to be the three reasons behind the weakness (in relevance order):

The narrative around oral GLP-1s

Schott’s weak FY 2026 guidance (shared early in December)

Stevanato’s low float (80% or so remains in the hands of the Stevanato family)

#3 is what it is and we can’t do much about it.

I discussed #2 in the NOTW. The Schott call seemed to confirm one thing: the weakness was company-specific and, if anything, it confirmed that Stevanato is probably going to take the US market by storm as its two closest peers have slept at the wheel (more on this later). What’s interesting about Schott’s weak guide is that it served to add fuel to the fire of the GLP-1 narrative. I believe that the notion of oral GLP-1s being a net negative for Stevanato is pretty misguided, for several reasons. This directly impacts point #1, and the goal of the article is precisely to discredit this narrative.

Before doing this, I believe it’s important to explain what a GLP-1 is, why it “solves” obesity, and the differences between orals and injectables (with their nuances). To help me with this, I have brought Gonzalo, a biochemist who writes great healthcare-related investment research in his newsletter Laboratorio de Inversión. I highly recommend his work.

GLP-1s: The “miracle” drug

Let’s begin today’s research piece explaining what lies behind Stevanato’s narrative shift: glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogs.

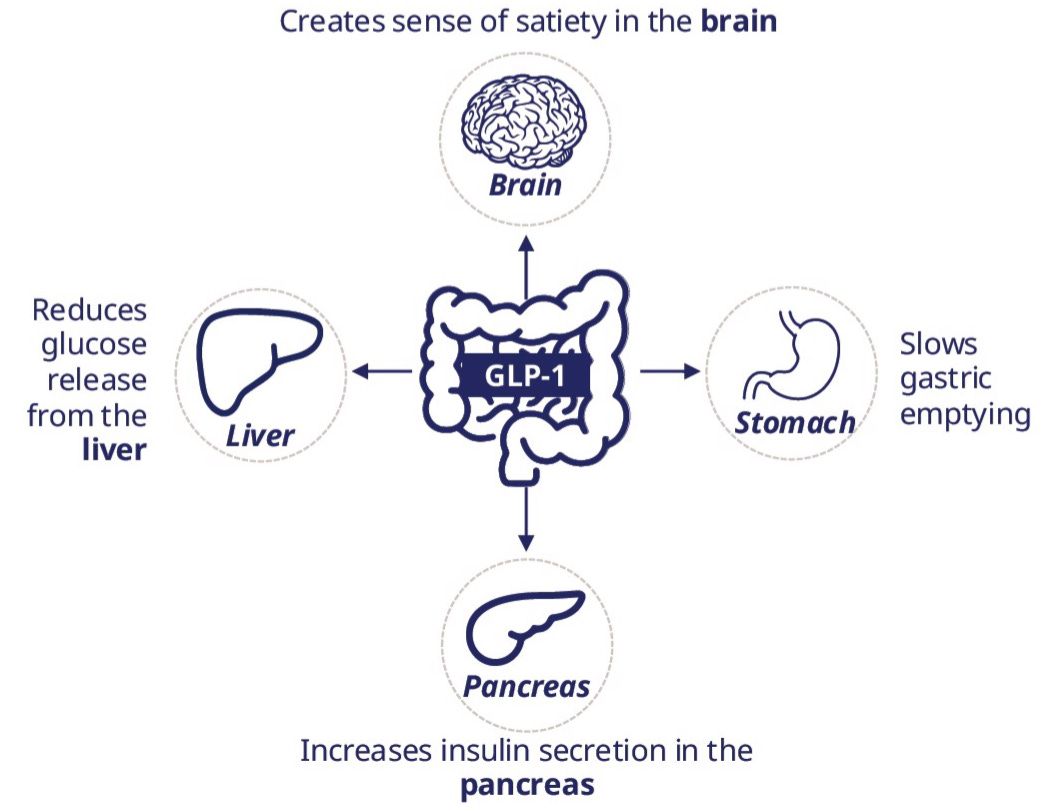

GLP-1 is a peptide, a chain of amino acids, that binds to GLP-1 receptors (GLP-1R) distributed throughout the body. When GLP-1 binds to GLP-1R, it:

Stimulates insulin secretion in the pancreas to regulate blood glucose levels.

Inhibits glucagon secretion, further stabilizing glucose.

Slows gastric emptying, increasing satiety.

Directly suppresses appetite at the cerebral level.

In essence, GLP-1 effects provide safe and effective glucose control for diabetic patients and have achieved up to 20% weight loss in overweight and obese individuals, a milestone previously unseen with other therapeutic options.

GLP-1 is a master metabolic regulator. However, it has a flaw: its half-life in the body is barely five minutes, severely limiting its effects. It is unfeasible as a therapy for obesity or diabetes, as patients would essentially need to be tethered to a continuous intravenous infusion.

To overcome this limitation, the pharmaceutical industry developed GLP-1 analogs, compounds designed to mimic the hormone’s action while extending its duration. The first major commercial success from this development was semaglutide, marketed by Novo Nordisk as Ozempic for type 2 diabetes and Wegovy for obesity.

GLP-1 analogs have triggered an unprecedented revolution in metabolic control, one of the largest markets in the pharmaceutical sector. With 1 in 10 adults suffering from type 2 diabetes and 4 in 10 categorized as overweight or obese, the combined market for these conditions currently stands at $100B and is projected to exceed $250B within the next decade.

Moreover, while GLP-1 analogs were originally designed for glycemic control in diabetic patients and subsequently applied to obesity, their utility has expanded into other metabolic conditions like NASH (fatty liver), and even cardiovascular disease prevention. The opportunity for this “miracle” drug seems limitless.

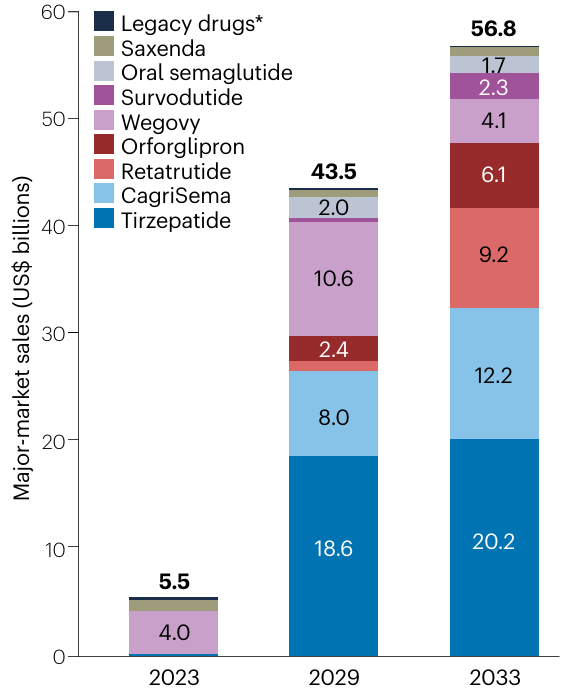

The downside for pharma investors is the cutthroat competition—just ask Novo Nordisk about Eli Lilly’s tirzepatide. We will focus primarily on Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly drugs, but keep in mind that over 100 molecules are currently in clinical trials, all fighting for a slice of the (ever-increasing) pie.

The good thing for the picks and shovel plays like Stevanato is that you do not really care who wins the GLP-1 race and even potentially benefit from cutthroat competition. As long as there is a diabetic, obese, or metabolically ill population — which not only exists, but is also growing — GLP-1 analogs will keep needing containment and administration solutions. The cheaper these analogs become, the potentially higher adoption we’ll see down the line, directly benefiting volume-focused providers.

Stevanato only requires two conditions to secure recurring revenue for years:

Commercial approval of a GLP-1 analog, which is not just probable, but a certainty.

The drug owner choosing Stevanato as a supplier, which is highly plausible given the existing oligopoly and Stevanato’s value proposition.

However, a fear has recently emerged that oral GLP-1 analogs will cannibalize the market share of injectables. While we believe this is a legitimate risk, we will see why it is unlikely to jeopardize Stevanato’s revenue. Before addressing that, we must understand how these drugs are administered.

Subcutaneous vs. oral GLP-1s

Unlike small molecules, biological therapies such as GLP-1 analogs are administered via weekly subcutaneous or intravenous injections. The reason lies in the digestive system’s hostility toward these molecules on multiple levels:

Palatability: Peptides like semaglutide cause a distinct bitterness.

Acid Stability: Gastric acidity destabilizes their molecular structure.

Enzymatic Degradation: Pancreatic enzymes degrade any peptides that reach the small intestine.

Bioavailability: Absorption of any remaining compound is severely limited.

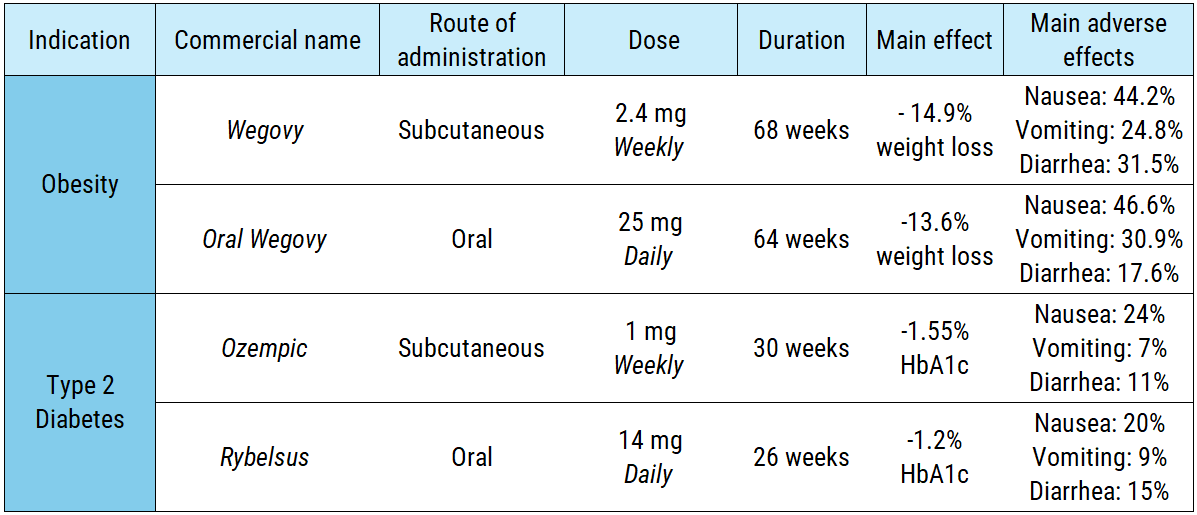

As a result, studies indicate that less than 1% of orally administered semaglutide reaches the bloodstream. To achieve a comparable therapeutic effect, patients must ingest a significantly higher daily dose, include absorption enhancers in the formulation, and take the medication while fasting. In clinical trials, the obesity-focused oral version requires 70 times more active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) than the subcutaneous alternative (175 mg per week vs. 2.4 mg per week). The diabetes version follows a similar pattern:

If manufacturing an oral version requires complex formulations, intensive dosing schedules, and strains the supply chain by demanding more API for the same therapeutic effect, why bother developing it? Because it is a strategy to boost treatment adherence and capture new patients.

Half of GLP-1 patients discontinue treatment within a year, and a significant portion of the population refuses to be anywhere near a needle. Oral formulations offer a therapeutic alternative for those with needle phobia. Furthermore, a daily dosing regimen aligns with most standard medications, making it easier for patients to maintain the treatment over time.

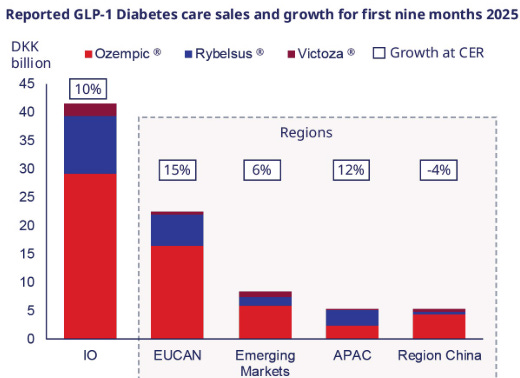

Until recently, the only officially approved oral version was Rybelsus—the semaglutide formulation for type 2 diabetes. However, its adoption has lagged behind Ozempic (the subcutaneous version). This shouldn´t come as a surprise, as Ozempic has a better profile of efficacy/safety (making it the preferred option for doctors), the diabetic population is smaller and is more accustomed to the routine of self-injection.

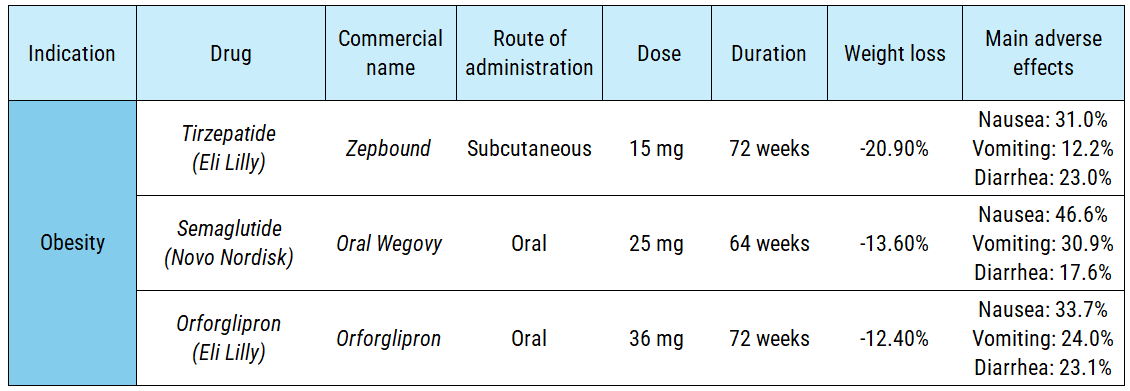

However, this landscape could shift next year with the anticipated approval of:

The oral version of Wegovy for obesity treatment (approved just yesterday)

Eli Lilly’s Orforglipron.

Orforglipron is a unique case among GLP-1s; it is a small molecule rather than a biologic, yet it still activates the GLP-1R. Its manufacturing and storage are more streamlined, and its oral administration is more convenient, as it eliminates the need for a 30-minute fasting window. While its efficacy and safety profile are comparable to oral Wegovy, it falls significantly short of Eli Lilly’s subcutaneous tirzepatide—the gold standard of GLP-1 analogs to date (technically a dual agonist mimicking both GLP-1 and GIP).

With the market arrival of oral Wegovy and Orforglipron, the risk for Stevanato appears evident:

If patients transition to oral GLP-1 formulations, Stevanato will see a decline in orders for its subcutaneous injection packaging solutions.

However, how much substance is there to this claim? The narrative starts to crater at the industry level (we’ll later explore the company-specific level).

The primary fallacy lies in viewing the GLP-1 market as a zero-sum game. Within the growing diabetes and obesity sectors, GLP-1 therapies are expanding at a compound annual growth rate of nearly 20%. This is a relatively nascent market driven by clinical efficacy that is truly unprecedented. The assumption that 100% of new patients would favor oral over injectable formulations is highly questionable. Instead, the arrival of oral GLP-1s is likely to attract needle-hesitant patients, effectively expanding the total addressable market (TAM) rather than displacing the existing one.

The second issue, closely tied to the first, is conflating broad estimates with actual physician and patient preference data. At a population level, 70% of people prefer oral medications over injections. A patient doesn’t need to “learn” how to take a pill, but self-injection requires instruction. While autoinjectors have streamlined the process, a learning curve remains, and discomfort persists for many. Consider an elderly patient with impaired vision or dexterity struggling to dial the dose on a cartridge; a physician is far more likely to prescribe an oral version if that patient is already managing a polypharmacy regimen—especially if the price point is at parity or covered by insurance. On the other hand, if a patient is not physically impaired or has any trouble with needles, physicians may tend to prescribe the subcutaneous versions granted that these have more efficacy.

Indeed, these percentages shift when examining real-world data. In a study of patients transitioning from injectable semaglutide to the oral formulation, 50% reported higher satisfaction with the pill, while the remaining 50% either preferred the injection or remained indifferent. Patients typically choose the most convenient route when efficacy and safety are comparable; however, in the GLP-1 landscape, the trade-off is complex: a daily oral dose for ease of use versus a weekly subcutaneous autoinjection with superior weight-loss efficacy. Stevanato estimates that oral GLP-1s will capture a 30% market share by 2030, though precise forecasting remains elusive. The key here is also being aware that this 30% will most likely be of a significantly larger market.

Finally, we must analyze the market’s trajectory. The case of Eli Lilly’s tirzepatide suggests we may be approaching a ceiling in terms of efficacy: aiming for weight loss beyond 20% might be neither necessary nor clinically sound. The current challenge is not inducing further loss, but preventing weight regain. In our view, the strategic priority is shifting away from higher potency and toward maximizing patient adherence—the true driver of long-term health outcomes and recurring revenue.

To achieve this, the patient experience needs to be simplified. Some experts suggest an “induction-maintenance” model: initiating treatment with subcutaneous injections for rapid initial weight loss, followed by long-term oral maintenance. However, current clinical evidence does not support this transition. In a trial where patients switched from subcutaneous tirzepatide to oral orforglipron, they regained an average of 5 kg previously lost. When patients were initiated into subcutaneous semaglutide and later switched to orforglipron, weight loss remained stable but new adverse effects appeared. This efficacy/security gap suggests that orforglipron is unlikely to significantly erode the market share of subcutaneous formulations. Peak sales projections for orforglipron hover around $15B annually—a figure eclipsed by tirzepatide, which recorded $10B in actual revenue in 3Q25 alone.

Note that Lilly described this transition from tirzepatide to orforglipron as ATTAIN-MANTAIN, somewhat signalling they embrace the induction-maintenance model. In short: Lilly is likely unwilling to cannibalize its injectables franchise.

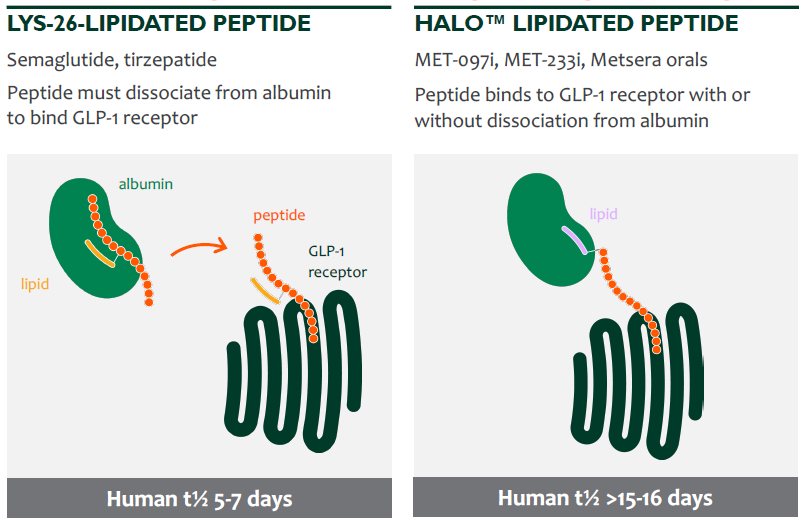

On the other hand, the recent bidding war between Pfizer and Novo Nordisk for Metsera (NASDAQ: MTSR) GLP-1s provides another signal regarding the market’s direction. Metsera was a biotech firm developing subcutaneous GLP-1s with a structural modification that allows them to activate the GLP-1R without detaching from albumin—a blood protein responsible for molecule transport and preventing degradation.

As a result, the half-life was extended to 15–16 days (compared to the one-week duration of analogs like semaglutide or tirzepatide) while maintaining equivalent potency, opening the door for once-monthly instead of weekly administration. Reducing injections from 52 to 12 per year represents a compelling way to improve patient adherence—a vision shared by Pfizer, which moved to acquire these assets for $10B. While such long-acting analogs could potentially be a headwind for Stevanato’s volume, they would significantly enhance the visibility of future cash flows by stabilizing patient retention.

In summary, while oral GLP-1s will undoubtedly become a popular and vital pillar in treating diabetes and obesity, it is unrealistic to expect them to relegate subcutaneous formulations to a secondary role. Despite the convenience of oral administration, subcutaneous versions are, and will remain, fundamentally more efficacious than their oral counterparts, and their production will be more cost-efficient due to significantly lower API requirements. Consequently, even as oral adoption increases, the overall GLP-1 market will continue its expansion. Rather than cannibalizing significant market share from injectables, oral formulations are more likely to expand the total patient population eligible for these therapies.

Where does this leave Stevanato?

Stevanato: a compelling opportunity

Stevanato and other fill & finish companies have been swept into the oral GLP-1 narrative. After reading the first section you should already understand why, but let’s recap it here. The argument goes as follows:

Oral GLP-1s will take the market by storm and therefore the incremental volumes for fill and finish companies from this market have become permanently impaired.

Some even go as far to say that, not only will incremental volumes be lower (as a more significant percentage will be “won” by orals) but also that orals will cannibalize the existing injectable volumes (so not only not a tailwind to future volumes, but also a headwind to existing volumes). There’s a lot of nuance to the topic that probably escapes this narrative and our goal in this section is to shed some light at the company-specific level.