The Advantage Of The Individual Investor

The premium subscription gives you access to all the content in Best Anchor Stocks, which includes…

All the deep dives

Recurring articles

Access to my real-time portfolio and transactions

Occasional webinars on various topics

A community of like-minded investors

A subscription the Premium + also gets you a quarterly Q&A with me to discuss anything you’d like.

If you want to know the type of content I share at Best Anchor Stocks you can read the Deere deep dive I uploaded a few weeks ago for free…

…or you can also read any of the other many free articles I have shared, just like this one!

You can also read the testimonials that existing subscribers have left. If you are a passionate and curious investor wanting to learn about high-quality companies, don’t hesitate to join Best Anchor Stocks!

When you started investing in the stock market, you probably asked yourself the following:

Can I, as an individual investor, beat the market?

Most individual investors are likely to underestimate their capabilities when answering this question, so the most likely answer would be “no, I can’t do it.” So what’s the thought process behind this answer? I believe it resides in other investors and mostly all market participants telling you that you can’t do it. Their rationale is the following:

Source: Business Insider

There’s historical evidence that supports the above statement. According to an IFA report, not many professional investors have beaten their respective benchmark over a 15-year period. Chances are slim:

With this empirical evidence on our back, why should we think we can beat the market? Many individual investors build a portfolio of individual companies with this goal, many of which don’t have the resources or knowledge that investment professionals have.

However, according to historical evidence (coupled with some common sense), we could argue that our chances are even lower than those of professionals. If a professional focused 24/7 on trying to beat the market with much more resources than we have access to can’t do it, what makes us think we can? Is it an illusion, or can we actually do it?

To answer this last question, it’s essential to understand our edge with respect to professional investors (if any). This is precisely the objective of this article.

Without further ado, let’s get started!

The types of edge an investor can have

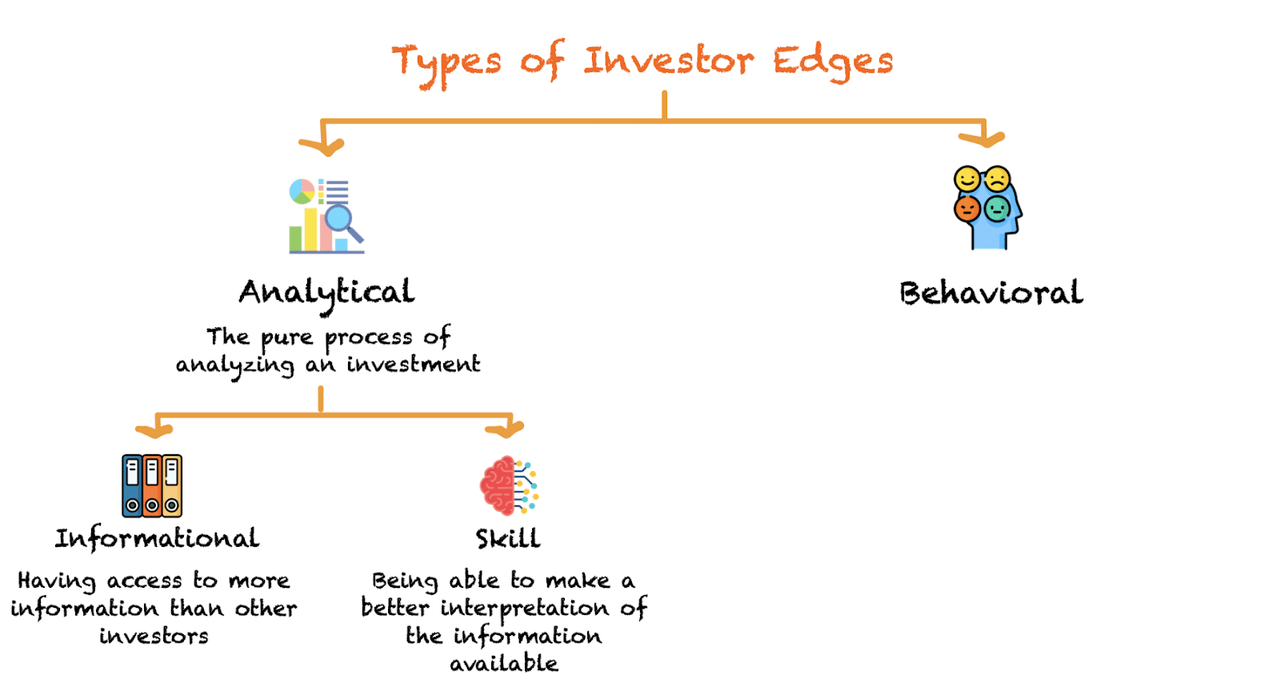

Before finding out what our edge is, we must understand what type of edges there are available to investors. I would divide it into two groups: analytical and behavioral.

These groups can be further sub-divided. Let’s go over them.

Analytical edge

An analytical edge refers to an advantage in the pure process of analyzing a company (fundamental analysis) or a stock (technical analysis). Inside this group, we have identified two sub-groups: informational and skill.

Informational refers to the availability of information for investors. If an investor has access to more information than another investor, we could argue that they have an informational edge. Information is key to making an investment decision, and having more of it accessible is a clear competitive advantage.

Skill refers to how an investor processes the information. If confronted with the same information, it’s unlikely that two investors would arrive at exactly the same conclusion or point of view about any company. Information is objective, but how investors interpret it is purely subjective. Warren Buffett would have a skill edge with respect to an inexperienced investor, for example.

Behavioral edge

Behavioral edges vary widely across investors. They basically refer to how investors behave after making an investment. We have also identified two somewhat related sub-groups: emotional and time.

Emotional refers to how investors manage their emotions. Emotions will vary widely across investors, and they are somewhat innate. Nobody chooses what emotional control they are born with, so we could treat it as a given. This said, we’ll see later how everyone can train themselves to manage their emotions.

Time refers to how an investor’s behavior aligns with their investment horizon. For example, if someone claims to be a long-term investor, but trades continuously in and out of stocks, their actions are not aligned with their strategy. On the other hand, if someone claims to be a long-term investor and acts coherently with their strategy, then his objective and actions are aligned, and the outcome should be much better.

We said that both are very related because the mismatch between objectives and actions (I will refer to this as ‘time flaw’) is almost always a result of poor emotional management. Conversely, aligning goals and actions is typically possible when investors can control their emotions. Later on, we’ll see how professionals have another flaw when it comes to time which is innate to their profession and doesn’t really depend on them.

So, what’s our edge?

Now that we know the types of edges any investor can have, we must try to identify what might set us apart from the market (if anything).

Do we have an analytical edge?

Let’s go straight to the topic by saying that we don’t think there’s any analytical edge we can enjoy.

We might have some sort of edge against other individual investors if we do deep research and aim to understand really well what the companies we hold do. Almost one year ago, I conducted a Twitter poll. The question was:

How many individual investors read 10Ks before investing in a business?

Of course, the replies only reflect respondents’ opinions (not statistical facts), but I must say that I agree with the outcome of the poll:

This doesn’t mean you should rush into reading 10Ks all of a sudden, but it shows that not many individual investors do their homework before investing in a business. Again, the above poll reflects opinions, but I have encountered many individual investors who have never read any SEC filing. This is fine if you outsource the research and trust who is doing it, but I doubt many of them do this, turning this practice into a recipe for disaster.

We could argue that investors who do thorough research indeed have an analytical edge with respect to many individual investors. However, the edge is not so much on having access to more information (informational edge) or being able to analyze it better (skill edge); it’s more about our willingness to access this information and trying to interpret it, which many individual investors fail to do.

Still, the problem is that markets are moved by institutional investors (big money), not individuals. So, do we have an analytical edge with respect to institutions? My answer:

We think publicly available information is more than enough for any individual investor to understand and judge an investment, but institutional investors might have a slight edge here. For example, they often have direct access to management, which we obviously don’t when the company already has a certain size.

On the skills side, we would be extremely brave (and probably quite stupid) to consider ourselves wiser and more experienced than the institution’s large research teams comprised of brilliant individuals. We don’t think we are the most intelligent and knowledgeable investors in the room, nor do we not believe intelligence is a crucial characteristic to be a good investor. There are two quotes by Charlie Munger that perfectly illustrate our thoughts when it comes to a skill edge:

If you think your IQ is 160 but it’s 150, you’re a disaster. It’s much better to have a 130 IQ and think it’s 120.

A lot of people with high IQs are terrible investors because they’ve got terrible temperaments.

The second quote is actually the most important one and takes us directly to the next section of the article.

Do we have a behavioral edge?

This is our edge. One thing is understanding a company and analyzing the available information there is on it, and a very different one is being able to isolate our decisions and our behavior from stock price fluctuations.

When it comes to an emotional edge, we must be careful assuming we have one, though. Why? Because volatility affects everyone. The catch here is that it affects everyone differently. Part of how we react to volatility is determined by who we are. Someone might have much more trouble seeing their money swing than another person that might be completely relaxed or have a neutral view on volatility. This said, and despite it being an innate characteristic, we can train ourselves to not care about volatility.

For example, if we study stock market history, we will see that volatility is the admission price to financial markets. This has always been the case. Another essential thing you should do to control your emotions is to avoid investing money that you will need over the short and medium term. Not checking daily how your portfolio is doing also helps. If you suffer the emotional impact of volatility, try to be less exposed to it. You’ll be happier, and your portfolio will probably perform better.

Something that Kris has done for years is visualization. By imagining how you react to your portfolio dropping by 50% and more over and over again, you become accustomed to the feelings that are associated with this, even though you haven’t lived through a 50% drawback. It’s not just thinking of the pain, however, it’s also thinking about the remedy, patience.

Behavioral does seem to be something that can help us perform better than professional investors. They can be as knowledgeable as they want and have plenty of information available, but if they cannot control their emotions, those two edges soon disappear. And they are trained not to control their emotions. Let me explain.

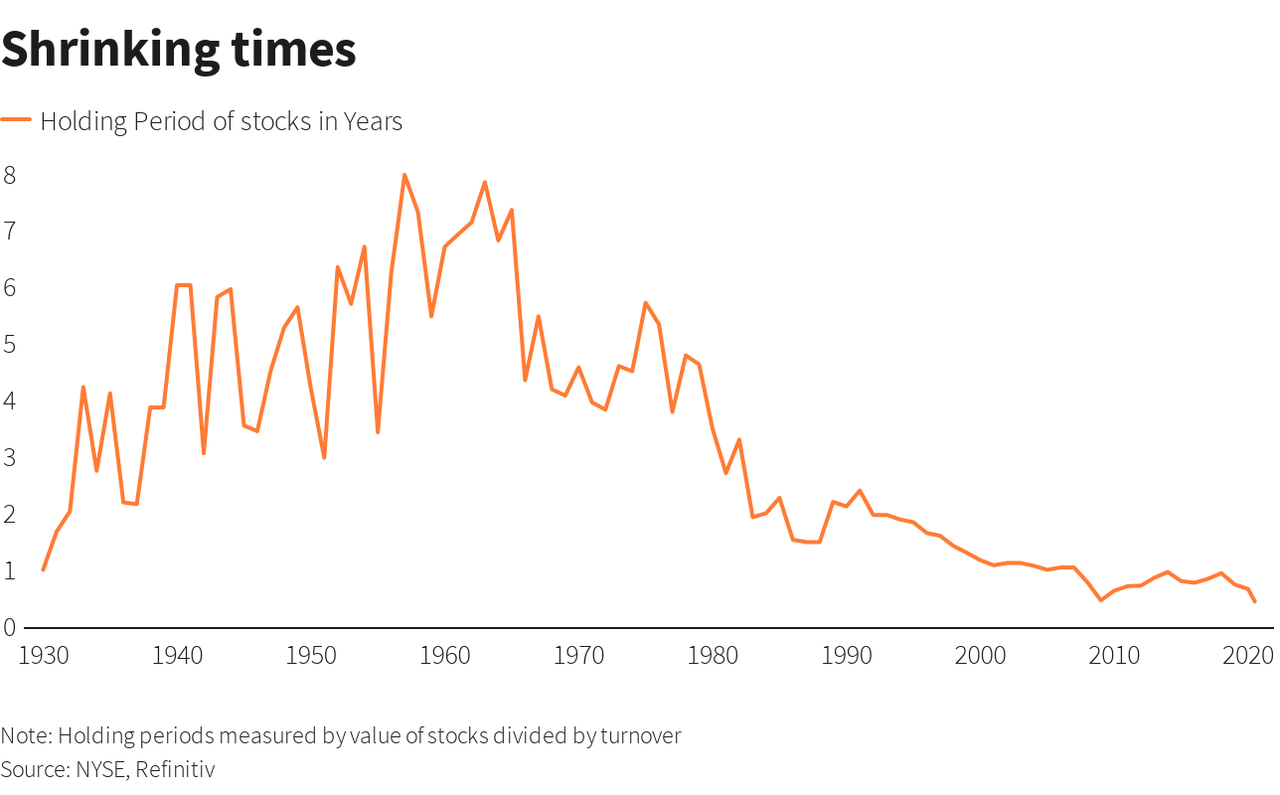

Our greatest edge lies in time. Having instant access to information has been great for the individual and professional investor, but it comes with some disadvantages too. Being exposed to dozens of headlines daily makes separating noise from signal much more complex. As a result, many investors confuse noise with signal, leading them to constantly trade in and out of stocks. Take a look at how the average holding period of stocks has evolved:

Unsurprisingly, the average holding period has collapsed to all-time lows. On average, investors are not capable of holding a company for more than 1 year, which is quite telling, as companies rarely change during such a short period.

The rise of the internet and individual investors' access to investing through mobile apps is undoubtedly a driving force behind this trend. However, it’s not just individual investors who are trading too much; institutions are too.

Let’s suppose that institutions are much better long-term investors than individuals and hold their positions for an average of 2 years (this is a made-up number, and I would say that the average might be even lower). Are 2 years enough to allow a high-quality company to compound capital for you? The answer is no, obviously.

So, if this period is not enough for corporations to prosper, why won’t institutions hold them longer? The answer lies in individual investors, once again.

Professional managers make a living from the fees charged to people who invest in them. The fees these funds charge are typically two-fold: maintenance fees and performance fees. Maintenance fees are those that the fund charges irrespective of performance to cover the general expenses, and performance fees are those that the fund charges only when the fund has made money. The amount made with these fees is higher when AUM (Assets Under Management) is higher because they are typically a percentage of AUM.

The investment industry is a highly competitive one, with many fund managers “fighting” for AUM. So, what do you think will happen if a fund performs poorly one year and underperforms its peers and the market? You guessed correctly: funds flow out and typically go to the best-performing funds. So the competition for AUM is soon converted into a competition for continuous alpha (alpha measures outperformance), which can severely damage long-term returns. It’s basically impossible to find an investor who consistently outperforms in all market environments, but still, most fund managers engage in that pursuit every year. As Terry Smith puts it in his book ‘Investing for Growth’:

Too often investors seek to find fund managers who can outperform all the time and in all market conditions. The trouble is that no such person exists. But the attempt to find this mythical creature leads to some investors moving their assets between managers, incurring costs and most frequently ditching a manager whose investment style is out of step with the current market in favor of one with recent good performance just as they are about to switch positions.

The search for continuous alpha has the effect of converting even “long-term” fund managers into momentum investors, and here is where our edge really lies. The good thing is you don’t have to follow the investment industry’s rules because your income doesn’t depend on your quarterly or yearly performance.

The market is a great valuator of companies over the long term, but there are always situations over the short term when it gets mispriced due to excessive reactions by individuals and institutions. This is when the savvy investor has to act, focusing on the underlying business and trying to abstract from stock prices.

I know that holding something for more than 5 years seems very long, but it’s really the only way to reap the returns of investing in high-quality companies, and it’s where our only edge really lies.

Can fund managers avoid the underperformance trap?

I honestly can’t blame fund managers for their behavior because it’s how the industry has been set up. Many companies make lots of money when investors trade (through commissions), so the stock market has been set up like a casino, where the goal is to reap as much as these commissions as possible. Of course, even if a fund manager knows that outperforming every year is impossible, the casino in which the stock market has been converted forces them to go for it, as they know that AUM will increase hand in hand with short-term performance. There is a clear misalignment of fund manager incentives (increasing AUM) with their long-term performance (which will lead to sacrificing AUM over the short term in tough times). So, what can they do?

I don’t think I am in the position of giving fund managers advice as I have never managed other people’s money directly, but I know what I would do. If a fund manager wants to align their incentives with their long-term orientation, the only way is to educate their shareholder base. If AUM comes from people who believe in the long-term story and don’t get scared of short-term shocks, fund managers won’t need to chase performance every year to avoid sacrificing AUM. A great example of a manager that has done this is Terry Smith, who doesn’t shy away from reminding Fundsmith’s investors that if they are not long-term investors, they should ask for their money and leave. I’ll say here that the current rotation of stocks in the Fundsmith portfolio sure seems a bit strange.

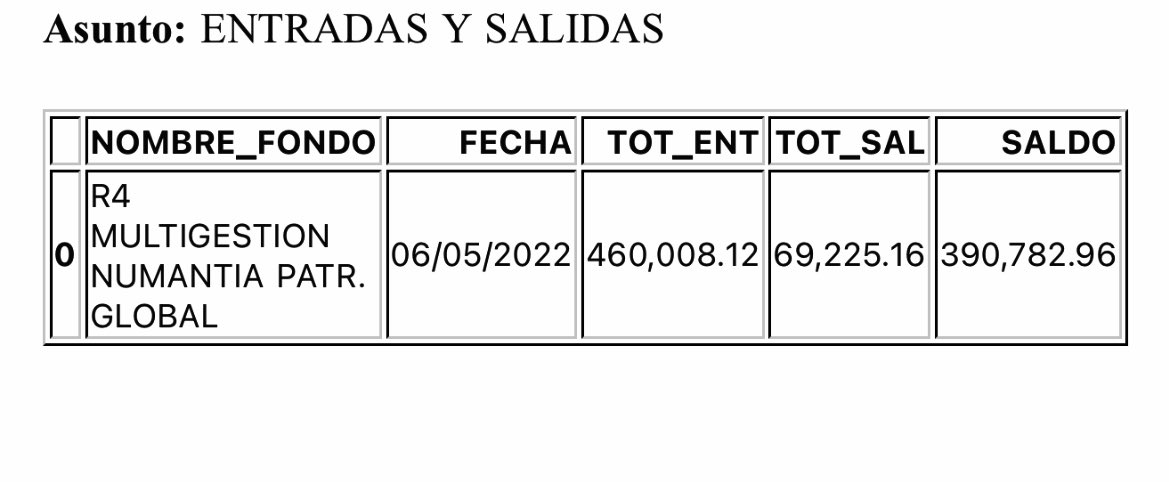

Having an educated shareholder base enhances the long-term performance of the manager’s fund. How? If fund managers have taught their investors to hold while stock prices are depressed, they won’t face redemptions when they are feared the most: during bear markets. If these investors go one step further and increase their investment in the fund when stock prices are depressed, the fund manager will have more money to increase his exposure. This example is pretty obvious when we look at another fund manager: Emérito Quintana. He is quite active on Twitter, where he shared this image during the most recent bear market:

Source: Twitter

“Total_ent” is the amount of money that has gone into the fund, and “total_sal” are the redemptions. As you can see, the difference between inflows and outflows is positive, giving him more money to invest at depressed stock prices, which might tilt performance upwards over the long term. The outcome above is impossible if the fund investors are short-term oriented and chase performance.

Conclusion

Individual investors should aim to outperform the market over a multi-year time frame, but all statistics indicate this is a very complex task. While these statistics are flawed because professional investors’ incentives are completely misaligned with long-term outperformance, we know it won’t be easy. The first step of our journey is identifying our edge, and we hope this article helped you understand where our (and your) edge is.

What do we have to do from now on? Search for high-quality companies and let them compound capital for us, focusing on the business and taking advantage of volatile stock prices.

In the meantime, keep growing!

Excellent article. I sometimes think that we underestimate good research and good common sense. One additional point I would add - individuals can invest where professionals can’t - very small companies. Institutional investors can’t participate because the liquidity is too low. Individuals can do quite well if they are interested in basic research

Hey Leandro! Just wanted to mention that I linked this piece form here:

https://www.libertyrpf.com/i/125971995/holding-period-of-stocks-over-time-measured-in-years

Cheers 💚 🥃