Resmed (RMD): The Sleep “Monopoly”

ResMed’s roots can be traced back to 1989 in Australia (g’day mate). Peter Farrell sought to address a condition that affected (and still affects) millions of people. The initial objective was to monetize good sleep by improving people’s lives, but the result was the creation of a $5 billion+ sleep monopoly (it ain’t so rosy as it sounds, though).

Sleep apnea is a sleep disorder that impacts hundreds of millions of people worldwide. In sleep apnea, the airway collapses or becomes obstructed, causing intermittent pauses in breathing that eventually lead to frequent awakenings.

This poor-quality sleep leads to a poor quality of life. Sleep apnea has been historically linked to a myriad of problems, like cardiovascular issues (including a higher risk of heart failure) and even divorce (as the poor-quality sleep eventually trickles to the sleeping partner).

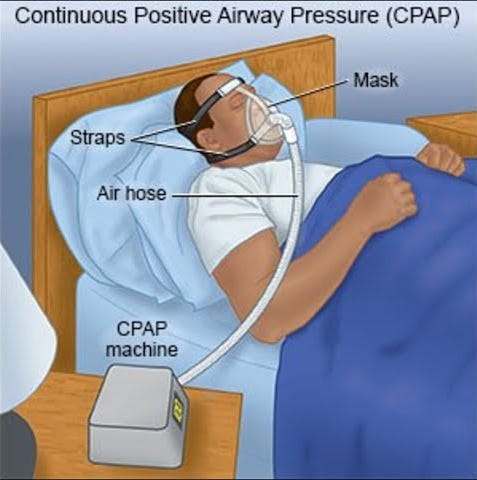

Peter Farrell set out to solve this problem and chose what has remained the gold standard to this day: CPAP (Continuous Positive Airway Pressure). With CPAP, the patient is continuously fed positive airway pressure to prevent the airway from collapsing. It sounds great at first until you see what it entails:

CPAP results are undeniably great, but (and I hope the image above has made this obvious) conversion and compliance have historically been poor. The reason is straightforward: despite significant advances in materials and comfort, not many people are willing to sleep with a mask on every day. Despite these drawbacks, CPAP has remained the gold standard to this day due to the lack of alternatives and has significantly improved many people’s lives.

CPAP allowed Resmed to build a highly profitable razor-razorblade model: the CPAP machine is sold once, but the patient’s LTV is monetized through subsequent and recurrent mask sales (typically once or twice a year). Let’s just say that Resmed seems to have done an incredible job monetizing sleep apnea:

Besides poor compliance, CPAP has historically faced an arguably larger bottleneck: top-of-the-funnel conversion. The sleep apnea market is supposedly so large that Resmed is a $5+ billion company growing at a 12% 5-year CAGR despite the market being largely untapped today. The tricky thing about market estimates is that a good chunk of them come from studies in which Resmed has played a direct or indirect role (so not entirely objective), but I’d say it’s undeniable that the sleep apnea market is multiples larger than what Resmed is monetizing today.

Studies estimate that around 50 million people suffer from sleep apnea just in the US, but that only around 8 million of these are diagnosed. A significantly lower number (around 3 million) remain compliant with CPAP. This ultimately means that, even though the top of the funnel is potentially enormous, Resmed is only seeing a tiny fraction of it. If I were to portray this using a meme, it would be something like this:

Getting on a CPAP is tough for several reasons. The first one is that the top of the funnel has historically been “starved” of patients, as many people are entirely unaware they might suffer from sleep apnea. Even when they were more or less aware that they might have it, getting diagnosed was not easy. Sleep tests were complex, typically requiring an overnight stay in a lab (polysomnography), and had to be prescribed by a sleep doctor. The result of these complexities was that few people got diagnosed, and therefore, they did not have access to a CPAP through reimbursement.

Resmed believes the industry now faces a new paradigm, one that promises to improve top-of-the-funnel conversion significantly. Two things have made this possible:

Wearables such as Apple’s and Samsung’s Watches, the WHOOP, and the Oura Ring now make sleep data much more accessible to everyone. The FDA recently approved Samsung’s OSA feature as a pre-screening tool to flag potential signs of moderate to severe OSA (Obstructive Sleep Apnea)

GLP-1s are creating an influx of people who “want” to get sleep apnea diagnosed, as this makes Lilly’s Terzipatide (Zepbound) available through reimbursement

Both opportunities have led management to believe that Resmed is currently at an inflection point like no other…

I actually think this could be the biggest demand generation opportunity in a generation for us.

Source: Michael Farrell, ResMed’s CEO (and the founder’s son)

This second point (GLP-1s) is arguably the most controversial and is somewhat existential to the Resmed story. Resmed argues that more people going to their sleep doctor (even if for a different reason than CPAP) is incrementally positive to the conversion story because both treatments are complementary (not substitutes). This means they believe that someone going to the sleep doctor (even if to get Tirzepatide) counts as one more potential patient in the funnel because they may end up being prescribed a CPAP once they’ve lost weight.

They also claim that GLP-1 patients are likely to remain more compliant with CPAP (they’ve shared some anecdotal data here) and therefore have a higher LTV (Lifetime Value). Bears/skeptics, however, claim differently. Obesity is not the sole cause of sleep apnea, but it’s definitely one characteristic that has been historically linked to the disorder. Losing weight is unlikely to cure sleep apnea, but it can ultimately reduce the AHI (Apnea-Hypopnea Index). The AHI categorizes the severity of the sleep apnea, and one could argue that as one goes down the scale, it’s less likely that two things will happen:

That they will get CPAP from the doctor (insurers may be less prone to finance equipment in less severe cases)

That they will adhere to CPAP

In all fairness to Resmed, around 40% of the current users of the company’s CPAP devices have mild sleep apnea, and these are unlikely to be impacted by GLP-1s. We are missing a key piece of data here, though. Even though we know that 40% of Resmed’s CPAP users have mild sleep apnea, we don’t know the penetration rate per AHI band. So, for example, 40% of Resmed’s users have mild cases, but it may well be that most of the US population that suffers from sleep apnea (the 50 million I discussed above) falls into this “mild” bucket, and therefore that the penetration ratio of CPAP is very low despite being significant for Resmed. This could mean that a larger number of people falling into the “mild” bucket makes the conversion story arguably more challenging than if they remained in the moderate or severe buckets (where it’s most likely they’ll get diagnosed and end up on a CPAP).

The reality is that nobody knows what will happen with GLP-1s, their impact on sleep apnea, and Resmed’s market. Resmed’s argument makes sense: the opportunity is so large that anything that helps them improve conversion and top-of-the-funnel expansion is additive, even if the total addressable market shrinks. The argument of the skeptics also makes sense: fewer obese people means a lower LTV and therefore Resmed’s opportunity becomes permanently impaired.

Besides the top of the funnel historically being a bottleneck, the post-diagnostics workflow has not helped either: getting on a CPAP is “tough”. Knowing if you might have sleep apnea has been greatly simplified with technology, but it only covers two steps of the journey toward a CPAP:

See a sleep doctor

Get a test done

Get a prescription from the doctor

Purchase the equipment from a DME (Durable Medical Equipment) supplier

The purchase of the equipment and subsequent consumables are, in many cases, covered by insurance, provided the patient remains compliant. This means that DME suppliers have every incentive to keep patients on the treatment for at least the first year (or else they would not get reimbursed). Resmed claims that, by then, people tend to remain compliant because enough time has passed to be able to measure the impact of CPAP on their lives. Resmed is not blind to this bottleneck and has innovated significantly to improve conversion and compliance (and successfully so). The company has done so through three types of software:

Patient-facing (myAir): allows patients to track their success while using CPAP and is key to retaining them longer and increasing adherence (the company claims that adherence is north of 87% for myAir users)

Doctor-facing (AirView): cloud-based patient management system so that doctors can monitor the development of their patients

DME-facing (Brightree): serves as an operating system for DMEs so they can demonstrate compliance to be eligible for reimbursement

Resmed is well aware that it relies on several friendly middlemen to support its journey, so it has embarked on a journey to create a digital ecosystem for them. Within its closed ecosystem, doctors are more likely than not to recommend Resmed’s CPAP (a decision the DME must comply with), and DMEs also have an incentive to sell Resmed equipment because the reimbursement flow becomes simple for them. These competitive advantages are strong in and of themselves, but it was the FDA that ultimately granted Resmed a monopoly.

The CPAP business used to be an oligopoly between ResMed and Phillips, but the latter faced a recall in 2021 and was banned from selling new equipment, allowing Resmed to ultimately take all (80%+) of the new CPAP sales. One can now understand why Resmed is so focused on driving the top of the funnel and conversion: they are the market! There’s no set date for Phillips’ return, but the longer it goes on, the more time Resmed will have to increase its installed base and, therefore, its potential consumable sales (masks).

But wait a minute…it ain’t all so rosy…

Up to here, you might have thought that the story is great…

For one, Resmed has an excellent track record of profitable growth, and returns have been exceptional. The company has consistently posted ROICs in the high teens to low twenties figures:

These returns and growth have been posted despite the aforementioned bottlenecks. One can only begin to think about what returns might look like if this is indeed the opportunity of a lifetime for Resmed. Another interesting thing about Resmed is that it has been strategically very well managed and has not been afraid to disrupt itself, not one, not two, but three times! So, what’s not to like?

Even though GLP-1s could be considered a significant threat (I’d say the net impact is still TBD), it’s not the elephant in the room. The elephant in the room is Apnimed. Apnimed is a pharmaceutical company that recently published its Phase III results for AD109, an oral pill that has shown promising results in treating OSA:

The LunAIRo trial met its primary endpoint, demonstrating clinically meaningful and statistically significant reductions in airway obstruction at 26 weeks. Participants treated with AD109 achieved a mean reduction in AHI of 46.8% from baseline at week 26 (vs 6.8% with placebo; p<0.001). The reduction in AHI remained significant at end of study (week 51, p<0.001). AD109 was generally well-tolerated, with the most common treatment-emergent adverse events being mild or moderate in severity, and consistent with prior studies. No serious adverse events related to AD109 were reported in the LunAIRo trial.

Apnimed expects to file an NDA (New Drug Application) with the FDA in early 2026, which might become a significant headwind for future CPAP sales. The reason is obvious: it’s much easier to take a pill every night than to sleep with a mask on, so compliance is likely to be higher. This trickles down to the intermediaries (insurers and doctors, definitely not the DMEs), who might be more open to this new treatment due to increased compliance. Will this be the end of CPAP? That will depend on cost and effectiveness, but I honestly don’t think so. Management doesn’t think so either (never ask a barber if you need a haircut), as they claim that more treatment options will expand the market, that CPAP will remain the gold standard for severe sleep apnea, and that (similar to GLP-1s) treatments will be complementary.

Management has also denied rumours that they’ll enter the pharma space, but they own a minority stake in Apnimed! Resmed’s strategy has been to take minority stakes in other treatment options and to slowly transition towards becoming a “sleep company” to hedge its CPAP exposure, but CPAP remains the main profit driver of the business to this day. Could Resmed end up buying Apnimed? Sounds like a possibility, but I don’t think that would be cheap at all at this stage.

What about the valuation

Even though Resmed is expected to face headwinds (and tailwinds) going forward, the reason that led me to pass on the shares was not this, but rather this in the context of the current valuation.

ResMed currently trades at a P/E multiple of 26x (with around $537 million in net cash), which is at the low end of the company’s historical range (yes, Resmed has not historically been a cheap company and for good reason):

The company’s multiple derated significantly in 2023 due to the “GLP-1 risk” and a significant deceleration in growth. Management held an Investor Day in September last year and shared the following 5-year outlook:

High Single Digits revenue growth

Earnings growth higher than revenue growth

If we assume Resmed outperforms these estimates and grows EPS at a 15% clip, we’ll need at least a 26x exit multiple to earn a 15% IRR (easy math). Given the launch of Apnimed’s oral and the narrative around GLP-1s, I’d say the most likely scenario is that the multiple compresses somewhat.

Now, I must say that I was pretty impressed with the company’s quality in terms of growth, margins, returns, and how it’s run. The Innovator’s Dilemma states that incumbents are typically disrupted because they have no incentive to disrupt themselves, but Resmed has disrupted its own business several times in the past and has effectively cornered the CPAP market (with a bit of help from Philips and the FDA). It’s undeniable, though, that a lot of things that have gone well for Resmed in the past are unlikely to repeat themselves in the future (you don’t get your closest competitor retiring from the market every day) and that the company might face incremental headwinds. This said, I believe it’s a great company to follow just in case Mr. Market decides to do something stupid.

Have a great day,

Leandro

Very good article but 2 risks (for the moment..) that make the valuation a rather high