Nvidia’s Lessons, Cyclicality, And The Impact Of AI On Financial Markets (NOTW#22)

Don’t forget that Best Anchor Stocks has a partnership with Finchat (the research platform I personally use), through which you can enjoy a 15% discount on any plan. Use this link to claim yours! You’ll find KPIs, Copilot (a ChatGPT focused on finance) and the best UX:

Hi reader,

The market somewhat recovered this week after the prior down week. There’s still plenty of “political” noise, so markets remain volatile. I also took the opportunity to discuss Nvidia’s earnings and what they can teach us, as well as some thoughts on cyclicality and the impact of AI on financial markets.

Without further ado, let’s get on with it.

Articles of the week

I published one article this week, in which I briefly explained why I am trimming my Intuit position. I explain the news flow the company has seen as a consequence of the Trump administration and also discuss why I think it’s isolated to a great extent from those risks.

Next week will be one with quite a bit of content, mainly earnings digests. I had several companies reporting earnings this week, so I will try to bring articles on all of those.

Market Overview

After a bad last week, markets somewhat recovered this week. Both the Nasdaq and the S&P 500 rose around 2%:

It was also not an uneventful week for the market. All the political noise continued, and the largest company in the world, Nvidia, reported earnings. Nvidia’s earnings were outstanding as the company continued to execute brilliantly at a scale that not many thought possible. The company has been a clear example of how misleading multiples can be for cyclical companies. High valuation multiples seem to make people believe that achieving the growth rates required to justify them is impossible, but cyclical companies have two growth engines at their disposal when coming out of a downcycle:

A rising market

Easy comps

Growth rates that look unsustainable compared to the company’s long-term track record can be pretty achievable when considering both growth engines. The market tends to account for this to an extent by granting the company a higher-than-average multiple. Still, my experience suggests that such multiples tend to be too pessimistic despite appearing optically high. There’s a lot of recency bias involved here; in simple terms, the market has a tough time believing how a company can go from “zero” to “hero” quickly, but that’s what happens to many cyclical companies. Multiples tend to embed the current sentiment to a greater or lesser extent. The last company I added to my portfolio is currently trading at 18x trough EBITDA, but it was trading at 40x peak EBITDA barely two years ago. Does this make rational sense? No (at least in my view).

Many investors fear high reported multiples but make no effort to calculate what normalized multiples are; it’s the latter that matters, not the former! I’ve also fallen into this “trap.” I used to be “afraid” of cyclicality, but I have evolved as an investor and now think it’s in cyclical (but secular) companies where opportunities are most abundant. The reason? There will be times when absolutely nobody will be willing to hold such companies, and they’ll eventually forget about their secularity (plenty of examples of this in my portfolio).

Another interesting thing about financial markets is that you tend to hear that they are efficient because market participants will jointly get every stock to fair value if there’s enough publicly available information. The reality is that the market is not efficient because consensus tends to be wrong quite a few times. There’s also an argument that says something like…

There are two sides to every trade, so when you buy or sell, a knowledgeable investor is doing just the opposite.

While the first part is evidently true, I don’t think the second one is. The reality is that when clicking the buy or sell button, you will be “trading against” one of three individuals:

A knowledgeable investor like Buffett, Druck, Rochon, or any other person who has done extensive research

Someone who has never opened an annual report

Algorithms

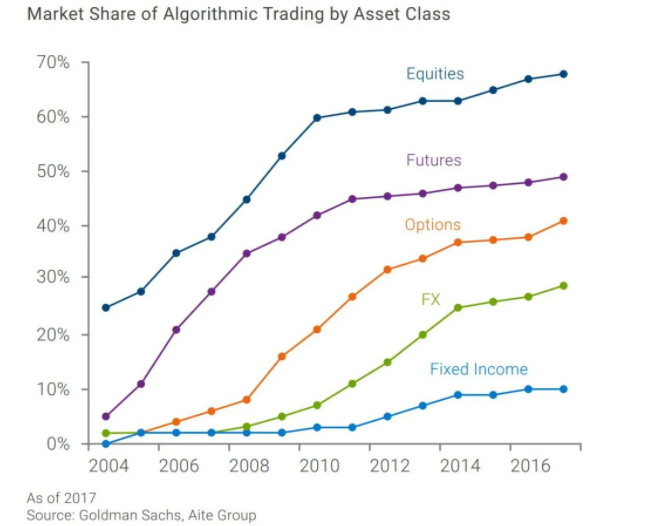

Sad as it sounds, the most likely scenario is that you are coming against #3. According to some estimates, algorithmic trading makes up a whopping 60%-70% of daily trading volume in the US.

These are highly “intelligent” algorithms that nobody would like to come against…unless your investment horizon is long. Algorithms don’t have a 10-year investment horizon, so as long as US markets continue to be flooded with their decisions, I anticipate investment horizon arbitrage will be prevalent.

People also believe that the arrival of AI will diminish market inefficiencies, but I believe the opposite will happen. This is what I wrote on X earlier this week regarding the impact of AI on financial markets:

Numbers don’t matter much when transactions matter the most: when there’s blood in the streets.

Pretty sure AI would’ve told you to sell Meta at $90. It’s already being used extensively by HFT and market makers and all they do is exacerbate emotions prevailing in financial markets at any given moment.

This is mostly a game of emotions, most people know what companies are good but few are willing to hold them when they go through bumps or periods of underperformance. Tough to see how AI changes this.

Will surely help with non-value add tasks, though.

AI is trained with large amounts of data that contain human biases, so it’s unlikely that AI will become rational when fed irrational historical data. Proof of this is that algorithmic traders have been using AI for years, and not only have they not made markets more efficient, but they’ve even made them more inefficient by amplifying short-term moves (up or down).

The industry map was somewhat mixed. The lowlights were probably Amazon and Google. I have no clue why Amazon came down, but Google’s drop might be related to the constant antitrust news the company gets:

The fear and greed index jumped back again to greed territory:

The rest of the content is reserved for paid subscribers.