NOTW #1: Investing Has Not Changed Much Over The Last 60 Years

Articles of the week, market overview, company news...

Hi reader!

This is the first article of its kind, so before going into the article itself, I’d like to explain what you can expect from it.

I will upload a ‘News of The Week’ every Saturday, which will bring the following content…

A recap of the articles of the week, just in case you’ve missed some that might interest you

A brief market overview, where I’ll make a summary of the week and will discuss any investment-related topic that I feel like discussing

My portfolio changes during the week (if any)

Watchlist changes (if any)

The news of the companies included in my portfolio

The first two bullet points will be freely available to you even if you are not a paid subscriber, whereas the last three will be reserved for paid subscribers. So even though it’ll say “Paid” on this article, there’s actually quite a bit of free content too.

Talking about the paid subscription…the initial 25% discount ends this Sunday, so if you want to take advantage of it before the price goes up be sure to do it over the weekend.

Note that I will upload the first deep dive the week of the 24th. This deep dive will be about a company that’s currently down 50% from highs, but which I believe follows a repeatable, profitable, and scalable model. If you want to sign up to read that deep dive and all of those that will come after, be sure to take advantage of the discount while it lasts:

Without further ado, let’s get on with this week’s articles.

Articles of the week

I uploaded two articles this week, both reserved to paid subscribers. The first one was my reflections on Elliott’s letter to Texas Instruments’ board. I believe the letter is fair but it’s also a tad misleading and a consequence of diverging investment horizons.

The second article of the week was Five Below’s Q1 2024 earnings digest. The company reported a pretty bad quarter, but there were some bright spots. I go over “the good, the bad, and the ugly.”

Market overview

Both indices had a good week, especially the Nasdaq (QQQ), which rose more than 2%:

Many people who focus almost exclusively on the indices believe that this strong start shows that “everything is overvalued.” While I have no clue if the market as a whole is overvalued, I would be cautious making that claim for all stocks included in the indices. As most of you might know, the indices have increasingly gotten concentrated toward Big Tech over the past months, which means those companies have been responsible to a great extent for the recent strength in the market.

This ultimately means that claiming that “everything is overvalued” based on the indices’ returns is a tad misleading. I obviously can only speak for the stocks I own or know well, but I am pretty confident that some of them are not remotely overvalued; if anything, some might be pretty undervalued. I’ve talked about this several times, but one of the advantages of owning a diversified portfolio is that you’ll rarely face a situation when every position is overvalued, so you’ll get opportunities to add to your positions rather recurrently. This obviously assumes that you have additional capital to deploy every month.

I shared on Twitter this week that I have been reading ‘Paths To Wealth Through Common Stocks’ by Phil Fisher, a book that was recommended to me by François Rochon when I interviewed him.

Phil Fisher wrote this book more than 60 years ago, and it’s honestly outstanding how well he described many of the things that still happen today. Let’s look at some examples.

More money has been lost by stockholders’ selling an outstanding stock on a small profit instead of holding it 25 years and obtaining say, - 3000% gain, than from all other foolish investment actions combined.

This quote has always been true and stems directly from the asymmetric nature of stock investing. An investor can “only” lose 100% on any given stock (and can probably realize the mistake before a 100% loss), whereas they can make multiples more on the upside. This means that if one buys good companies at reasonable valuations, selling too soon is, on average, much costlier than waiting for confirmation of a broken thesis. I personally need to be very sure that the thesis has changed or that it has been permanently impaired before selling.

Then there’s a quote that I honestly think describes most market participants:

The man who in the investment field pretends to know everything about everything is the one who can be quite dangerous.

Social media has given a voice to almost everyone, but this has made many believe that they must have an opinion on every topic. All the people I know who are curious and read a lot have one thing in common: they are very aware that they can’t have an opinion on everything. The quote above becomes very palpable when a stock is doing poorly. Thousands of people who have not even taken the time to know what the business does will have an opinion on its “terrible” future; why? I don’t know, but this is probably where engagement farming has taken us! Fear sells much more than hope.

I’ve always advocated for the concept of “risk-adjusted returns.” I obviously did not come up with this term myself, but I think many people focus too much on returns and not enough on risk. Many believe a 20% CAGR is much better than a 15% CAGR, regardless of the risk assumed. I don’t believe this is remotely the case because the level of risk should be a critical variable in determining what investment is better. Phil Fisher describes these dynamics succinctly with this quote:

If the company has developed to a point where the probability of tripling its value in the next 10 years involves only about half as much risk of not so growing as was the case ten years before, the stock might be just about as attractive an investment today.

The tough thing here is that risk is not measurable (or maybe not to the same extent and preciseness as returns), so an investor must judge the level of risk after doing fundamental research. I own companies in the portfolio that are riskier than others (at least to my judgment), and I obviously don’t underwrite the same IRR for these as for my “safer” stocks.

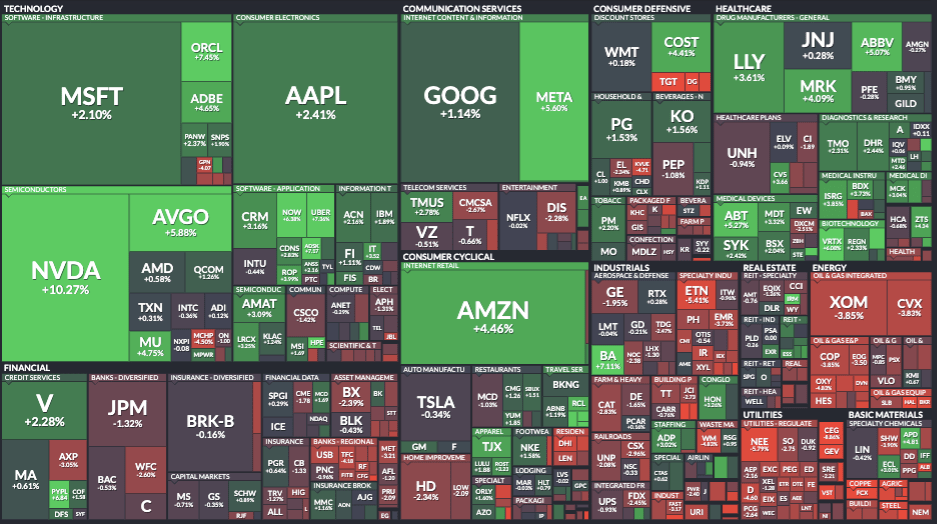

The industry map was mixed this week, which is consistent with the fact that the Nasdaq rose considerably more than the S&P 500:

Despite the Roaring Kitties and whatnot, the fear and greed index actually decreased a bit and is close to fear territory. I don’t think this indicator is the holy grail of sentiment, but there are probably better opportunities when it’s at extreme fear or fear than when it’s at extreme greed.

What this indicator does portray pretty accurately is how fast market sentiment can change. The fact that companies don’t change as fast as their valuations do is what allows investors to profit from the dislocations:

This is all for this week, as the rest of the content is reserved for paid subscribers. Don’t forget that the ongoing introductory discount will be live until Sunday: