Is ASML a buy today?

The moat, investing in semis, and the valuation

Hi reader,

I’ve followed ASML closely for several years and have written many articles on the company (9 on Seeking Alpha, to be precise), especially when the stock was out of favor. I thought it would be a good idea to write an article discussing three critical topics for the company…

The moat: this is one of the things that makes ASML such a great company. I believe it’s a somewhat misunderstood topic, as many tend to think the moat is purely technological (which isn’t the case)

Why one does not need incredible forecasting ability to invest in semis: again, this is another misunderstood topic, as many believe one needed to foresee the rise of AI to take advantage of the recent strength in the sector (not really true)

The valuation: always a key topic for any company, and it will be interesting to see where ASML stands after the run-up

Without further ado, let’s get on with the first topic.

Is ASML’s moat purely technological?

Many believe that ASML’s moat relies purely on technology, arguing that technological disruption is the company’s most significant risk. While there’s some truth to the idea that technology is the company’s main advantage and disruption its main risk, this doesn’t mean it’s the only competitive advantage at its disposal. Even if it were the only one, I’d go as far as to say that the technological gap between ASML and its competitors also matters, and it’s not just a fact of what the company’s systems and those of its competitors can do, but more about how profitably they can do it.

I believe there are three tiers to ASML’s moat, outlined in the image below and explained in more detail afterward. I’ll also talk about an overlooked advantage that helps this three-tiered advantage remain durable:

Tier 1 Defense: Decade-long head start in lithography

This is the advantage that many people typically cite as the only source of the moat. ASML has been investing in lithography for decades. While the investments are known to have been worthwhile in hindsight, this was not the case when the company started putting resources behind this technology. ASML’s management basically wagered the entire company in lithography when it wasn’t even clear if this would be the best technology to shrink transistor size. The takeaway is that, in the same way we are talking about ASML as a success story, we could well be talking about it as a failure.

This decade-long headstart and the billions the company has poured into developing its EUV technology set it miles ahead of the competition. Just for context…the company has invested more than $15 billion into its EUV technology, which took more than two decades to develop until reaching high-volume manufacturing.

Many will say that Chinese manufacturers have been achieving technological breakthroughs lately, spurred by the export restrictions the country is facing (EUV has always been banned from being exported to certain customers in China). While it’s undoubtedly true that several Chinese suppliers have made some technological advancements, the cost component of the equation is unclear. It’s not only about what chips you can manufacture but at what scale and price. This said, Chinese manufacturers are also likely to face some constraints when trying to go below the 2-nanometer node, as immersion DUV multi-patterning is unlikely enough.

ASML has a significant technological head start that is unlikely to fade soon, especially given the other tiers of the company’s moat.

Tier 2 Defense: Complex and sometimes exclusive supply chain

The technological moat in EUV is not the only thing that will keep competition at bay. All this relentless innovation has not only come from ASML’s side.

EUV machines are made up of more than 100,000 parts, some of which are high-tech. These parts are manufactured by various suppliers who have invested considerable money and time into their development. Of course, these suppliers could also sell these parts to ASML’s future competitors, right? Well, it turns out that, in some cases, they can’t.

ASML’s management knew that an essential part of the moat would come from its supply chain, so it converted some suppliers into strategic partners by signing exclusivity agreements with them and even owning a portion of these companies. Let’s take Carl Zeiss as an example.

Carl Zeiss SMT GmbH is our single supplier, and we are their single customer, of optical columns for lithography systems.

We have been in a partnership with Carl Zeiss SMT Holding GmbH & Co. KG for over three decades and we also hold an interest in the company. … We have an exclusive arrangement with Carl Zeiss.

This means that a competitor would need to replicate not only one company but many, as a good portion of these companies are either owned by ASML or have an exclusivity agreement with the company. Replicating one company is tough; replicating an entire ecosystem is tougher (put mildly).

Tier 3 Defense: switching costs

Both ASML’s technological advantage and “exclusive” supply chain make it almost impossible for a competitor to close the EUV gap quickly. However, even if any company could do it, there’s still an additional line of defense: switching costs.

Due to the complexity of EUV lithography systems, they are very complex to use too. This, combined with the fact that ASML’s EUV is the only one in the market, gives customers no choice but to use this system and train their employees on it. This means there’s a significant learning curve, and I don’t think that, even if a competitor comes in, customers would be willing to switch so quickly and go through all the hustle of employee training again. This is especially true considering that new, unproven technology can bring significant terminal risk to a company already enjoying quite strong margins (like the leading foundry is).

I don’t think this “tier 3 protection” will be relevant for the next decade, but it might become relevant after that if competition can manufacture EUV systems or any other alternative.

An additional defense tier

Something that’s not widely discussed is that ASML’s good relationship with customers helps it significantly lengthen the durability of its moat. ASML has a monopoly in EUV systems, so it could potentially take one of two routes…

Treat its customers poorly and reduce customer surplus to a minimum. Even if unhappy, these customers would have no other option but to purchase the company’s systems.

Treat its customers well, as if the company had no monopoly.

Management has chosen the second option, which makes sense for several reasons. The first (and probably most important) is that happy customers don’t have any reason to look for alternatives. During its early innings, ASML relied on customer investments to make ends meet. I assume the company’s customers today will not wager billions on alternatives so long as ASML’s systems work and allow them to be profitable.

The second reason is that ASML relies on its customers’ roadmaps to develop new technology. Transparency is key in the semiconductor industry, and unhappy customers could result in lower roadmap visibility, which might eventually hijack the company’s long-term R&D roadmap.

All in all, while I don’t consider this strategy of treating customers well (despite not having to) as a competitive advantage per se, I do believe that it maximizes long-term value. The reason is that it works in favour of ASML by helping it fence competition for longer. It’s unlikely any other technology will compete against ASML if customers don’t want to give that technology a try or even money to develop it. So long as customers are not incentivized to look elsewhere, ASML is in a good position.

Let’s not forget that the main risk for ASML is not that someone copies its technology (as this would infringe intellectual property rights) but that a new technology either replaces lithography entirely or drastically reduces the need for lithography in the chip manufacturing process. Both of these don’t seem close, but they are always worth watching.

Do investors need forecasting abilities to invest in semis?

Another interesting topic regarding ASML and other semiconductor companies in general is that of forecasting abilities. What do I mean by this? Many people claim that to enjoy the gains in Nvidia (NVDA), an investor would’ve needed to be able to forecast the AI wave, be very lucky, or both. In my opinion, this completely misses the point of investing in the semiconductor industry.

Investing in semiconductors is not about forecasting the next application that will require semiconductors; instead, it is about understanding and feeling comfortable with the fact that, whatever comes, more and more advanced semiconductor content will be needed in the future. How many people foresaw smartphones two decades ago? How many people foresaw cars with $2,000 in semiconductor content? I don’t know the answer, but neither of these forecasts were needed to understand that technology (and thus semis) would play an increasingly important role in the future. This is, by the way, one of the reasons why I don’t understand the following chart that’s being shared by many “doomers” on social media:

This chart’s goal is straightforward: to show that the period we are living in today is similar to that of the dot-com era. I beg to differ, at least when presented with this chart. After 20 years of technology increasingly becoming dominant in every industry, what did people expect? To see technology as a percentage of the S&P 500 stay at the same level? This doesn’t seem like a rational expectation. Another way of disproving this chart would be to overlay it with the proportion of S&P 500 profits that come from tech companies today compared to the early millennium (period when few tech companies were profitable).

Anyway, what I am trying to say here is that investing in semis is not about forecasting the next application that will demand semiconductors; it’s about understanding that whatever application that might be, semis will be an integral part of it. If semis are an essential part of future applications, then it’s logical to think that ASML will do pretty well, considering that its systems are mission critical in the chip manufacturing process. As Peter Wennink rightly pointed out in a past earnings call…

Why didn't we see this massive and big demand for our products coming?

Because we simply did not connect all the dots. And it's still a challenge today to keep connecting all the dots. But it's the value of Moore's Law, which is basically reducing the cost per function that will drive our business, and we'll create these building blocks for growth and solving some of humanity's biggest challenges. And we are a strong believer in this. And Moore's Law is alive.

Moore’s Law creates this sort of reinforcing flywheel through which new technological innovations increase the probability of future technological innovations and so forth. Who knows what AI might bring in the future? Few, but the good news is that we don’t need to know. We only need to know that semiconductor content will most likely go up in the future.

ASML’s valuation

A key topic for any potential investment should be valuation. No matter how high the quality of any company is, we should always monitor its valuation to understand if it continues to be a good investment. Now, when to sell is a somewhat subjective topic. I know many people will sell a high-quality company as soon as it reaches what they believe to be “fair value,” but I don’t think this is the most appropriate choice for three main reasons…

There are tax implications to selling, so disposing of a company purely due to valuation reasons might not be the most tax-efficient long-term choice

High-quality companies tend to surprise to the upside and these surprises are rarely baked into prices. Selling a high-quality company is forfeiting this optionality.

Selling requires making a new decision on where to put the money to work, and good decisions are scarce. Note that if you only expect a holding to provide you with say 6% forward returns, selling is only rational if you believe to have found an idea that allows you to compound at a faster rate (taking into account the lower initial investment amount due to taxes)

You might or might not agree with this, but that’s how I view selling. I very rarely sell my companies, and if I do, this tends to do more with a deterioration of the business than with valuation. Some would argue that holding a business is the same as buying it today, but I don’t really agree with that for the above reasons.

Anyways, the goal of this section is to answer the following question…

Is ASML a buy today?

Since I started my position in the company in March 2022, the stock has appreciated 81%. I rarely buy my positions in one go, so I managed to lower my cost basis to $555 through subsequent adds (thanks to the market’s volatility). This means my position is up around 91% without accounting for dividends.

Now, does this indicate the stock is expensive? One of the things that I struggle with the most is averaging up. I think this is fairly normal since we tend to believe that we are buying a more expensive stock if we are doing so at a considerably higher price, which might or might not be the case. What I mean by this is that ASML might be a better buy today at $1,000 than at $800 two years ago, even though the price is higher today. This seems very straightforward, but it can undoubtedly play with our subconscious.

I’ll use two valuation methods to assess the current valuation to avoid overcomplicating things too much…

The FCF-yield method

Management’s guidance

Without further ado, let’s get on with it.

The FCF yield method

Through this method, I calculate the company’s current FCF yield and try to understand whether it can lead to double-digit returns once we assume a conservative growth in Free Cash Flow going forward. If we assume no changes in valuation, adding both (the current FCF yield and the expected FCF growth) up should give us a pretty good idea of our potential return.

It’s obviously not the most comprehensive valuation methodology and has drawbacks (for example, we are not assuming changes in the valuation multiples), but it comes in handy when we don’t want to overcomplicate things too much.

ASML’s EV is currently €385.4 billion, and the company has reported a FCF over the last 12 months of €2.4 billion. This yields a FCF yield of 0.6%. This obviously seems extremely expensive, but there are several caveats we must consider when looking at the company’s free cash flow…

It’s significantly impacted by changes in the down payments made by customers before receiving the equipment. In the current industry environment, ASML’s management has flagged that customers have chosen to “keep” more cash to weather the challenging times, therefore impacting the company’s cash collection cycle.

Capex plays an important role. ASML is currently undergoing a significant expansion plan to meet future demand, which has made Capex grow considerably since 2021, from €900 million to almost €2 billion. Of course, not all of this increase comes purely from the expansion (the business has become larger and therefore Capex has naturally risen), but it’s fair to assume that a good portion does. Note that many believe ASML to be a Capex-heavy company due to the nature of its business, but numbers say otherwise. Over the last decade, the company has averaged a 6% Capex to Revenue ratio. The reason is that the supply chain bears a good portion of the Capex, where ASML acts primarily as an assembler.

Both of these impacts should somewhat correct themselves going forward. The cash conversion cycle should eventually go back to a more normalized level, and the high Capex will eventually subside once a good portion of the expansion plan is complete (sometime around 2025).

ASML generated €9.9 billion in Free Cash Flow in 2021, putting the company’s current adjusted FCF yield at 2.5%. Now, 2021 was aided by several tailwinds that might not represent a normalized environment. For example, ASML enjoyed a lot of down payments during that time due to the supply crunch in the industry and was operating at capacity. Both of these are unlikely to repeat anytime soon, but there’s no denying that the current FCF is not normalized either. Common sense would put the company’s normalized FCF yield somewhere around 1.5% and 2%. Is this cheap? It isn’t, especially since we would need to underwrite around an 8-9% FCF growth over the coming years with no change in valuation to get to a double-digit return. There’s not much margin for error.

It’s true, though, that an 8-9% growth rate seems pretty conservative, not only based on management’s guidance (which I will go over in a bit), but also based on analysts’ expectations. Analysts are estimating more than €12 billion in Free Cash Flow in 2026. While this leads to a significantly higher CAGR than the 8-9% forecasted above, we must not forget that we already accounted for a good portion of this CAGR by normalizing the current free cash flow yield. So, based on the FCF yield, can ASML offer double-digit returns going forward? It sure can, but the margin for error is not huge here.

This is something I rarely say for any company, but due to its volatile cash flow, the accounting numbers might be a better way of looking at ASML’s valuation. So let’s do that by looking at management’s guidance.

Management’s guidance

During its 2021 Capital Markets Day, ASML’s management came up with some 2030 guidance. Based on this guidance, I built a high and low-end scenario of net income:

The company generated €7.8 billion in net income in 2023, meaning that management expects profits to CAGR between 9% (at the low end) to 17% (at the high end). The range is pretty wide, but we must not forget that management tends to be conservative because they can’t grasp what Moore’s Law can bring.

Now, let’s work on some scenarios. I’ll assume…

The company repurchases around 1.5% of its shares annually throughout the next 7 years. I think this makes sense based on what the company has managed to do over the last 10 years. This means the company gets to 2030 with 352 million shares outstanding (approximately)

A 10% required return by shareholders

50% of earnings are paid out as dividends each year, and I am assuming no reinvestment

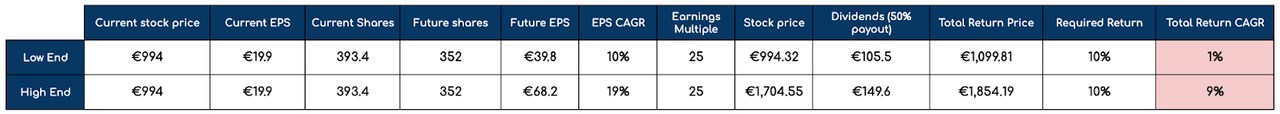

A range between 20 and 25 earnings multiple by the decade’s end, which might seem conservative considering the company’s past valuation but helps us account for a potentially diminishing growth runway

Similarly to the FCF yield method, this exercise doesn’t show much of a margin of error. For example, assuming the company trades at a 20 times earnings multiple in 2030 and considering management’s high and low guidance ranges, shareholders should expect a total return CAGR somewhere between -1% and 6%, in the worst and best-case scenario respectively. Not great:

Assuming the earnings multiple is 25, shareholders should expect a total return CAGR somewhere between 1% and 9%. Better, but not great considering we are assuming a 25x multiple 7 years out…

As I said before, management tends to be conservative and ASML might well beat the top end of its guidance by 2030. Still, I’d prefer to add to my position when the market is not pricing that in rather than when it is. There are also other things we should take into account when analysing valuation. Let’s go over these briefly.

Something worth taking into account when looking at the valuation

Multiples might look like standalone numbers, but they typically embed a wide variety of factors. For ASML, we must take into account several of these when assessing valuation, besides the strong moat I already alluded to earlier in this article…

The company’s backlog provides it with plenty of visibility. ASML currently has a multi-billion dollar backlog that gives investors quite a bit of visibility and “insulates” the company to an extent from any future downturn. This is something I wrote in my article ‘ASML: Don’t Worry About a Bust’ which was uploaded when fears of a potential downcycle were rampant.

ASML has a monopoly in EUV, a technology that is starting to gain penetration and that will likely make up a more significant portion of the company’s profits going forward. This is important because having a monopoly allows ASML to “own” its destiny. This is one of the reasons why I believe in management’s guidance to a greater extent that I would for another company.

The good news for patient investors is that there’s no need to rush. ASML operates in a cyclical but secular industry, meaning that it typically gives opportunities as market sentiment shifts. This has been this way historically and I doubt it will change going forward. The advantages of investing in such industries were succinctly pointed out by Parnassus Investments founder Jerome Dodson in an interview with John Rotonti:

Many of our biggest winners have been companies that operate in cyclical industries with secular growth drivers. When their business cycle turns down, investors become overly pessimistic and extrapolate the current negative conditions. They forget the cycle will eventually turn, throw in the towel on the secular growth drivers, and engage in panic selling, pushing the stock to bargain-basement levels. But eventually the cycle turns, and the stock soars higher. It's difficult to have the courage to buy when everyone else is selling, and this has been an important part of our success.

Judging by the current environment, one would think that it’s impossible for semis to fall out of favour, but I’ll take the under. It’s honestly astonishing how some secular long-term trends end up being completely disregarded by market participants when stock prices drop. It has happened before and it will probably happen again.

I will not add to my position at these prices and I believe a good buying range would be somewhere between €700 and €800. Such prices would give me more visibility toward a double-digit return which is ultimately what I am striving for. As you can see below, the low-end ranges still fall below my expected return, but I believe the risk of ASML missing these is low:

Conclusion

ASML is an outstanding business operating in an attractive industry where one does not need a magnificent forecasting ability to bet on. However, the current valuation leaves little room for error and thus means that I will be waiting for better opportunities to add.

In the meantime, keep growing!

Disclaimer: As of the moment of this writing, the author might have positions in the securities discussed. The article is intended with information purposes only, do your own due diligence.

Great article! Thank you, Leandro.

Thanks for this deep dive. Well done.