Is Alcohol Consumption in Terminal Decline?

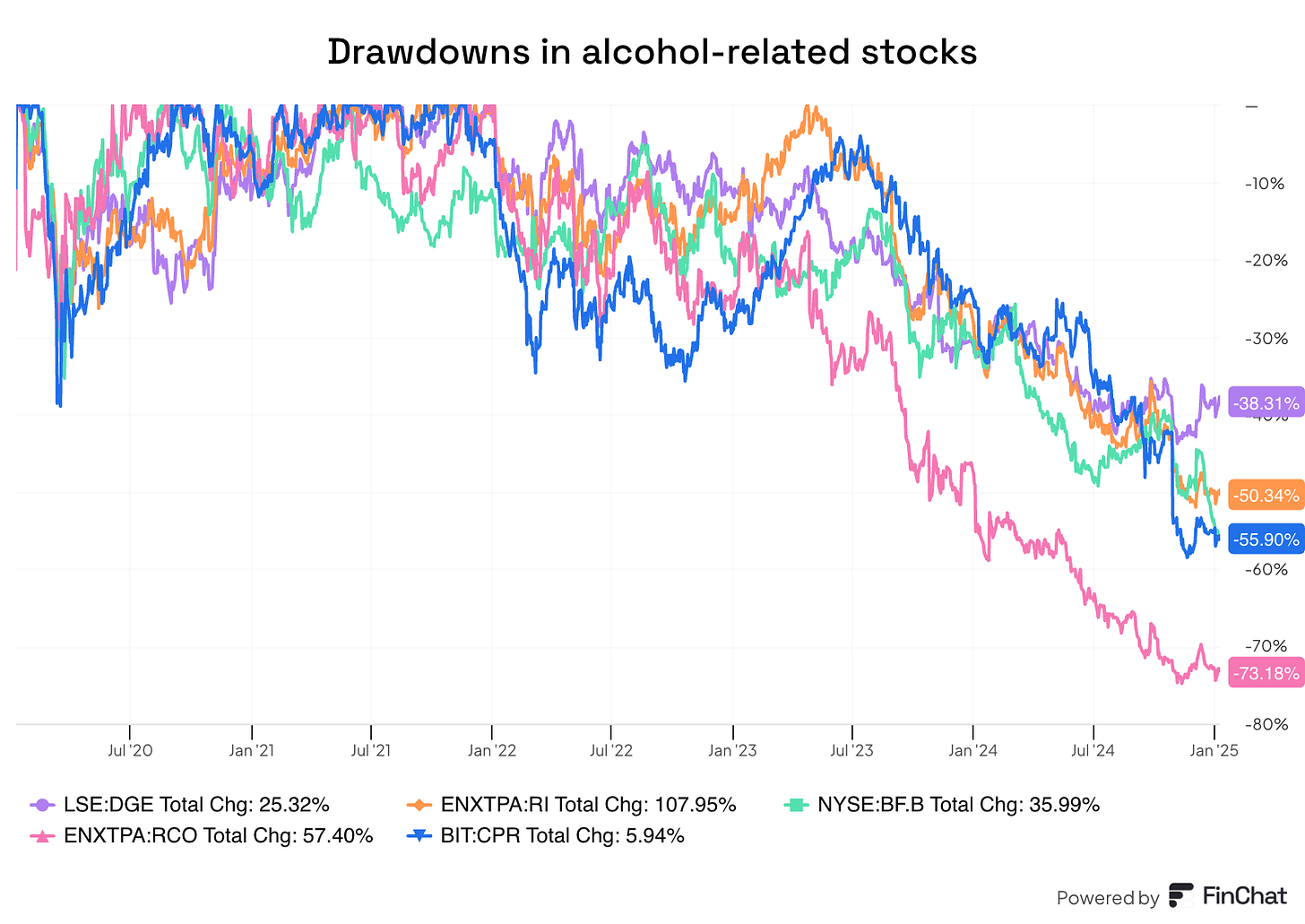

It’s no secret that alcohol-related stocks have seen better days. After strong excitement during the post-pandemic drinking surge, the stocks of well-known spirits and beer brands are significantly off ATHs despite indices being at or close to ATHs:

Most companies shown in the chart above are undergoing one of the (if not THE) most significant drawdowns in their history as publicly traded entities. Like it tends to happen in the stock market, regardless if we think it’s reasonable or not, there might be a (two-fold) reason for the drop. First, the pandemic boom and bust cycle. The post-pandemic period led to a demand explosion caused by increased socialization, which coincided with a global supply crunch. This demand/supply imbalance led to distributors stocking ahead of an already inflated demand and caused a double-whammy for the industry in the out years: destocking into a lower-demand environment. According to Diageo, distributor inventory levels reached the high end of their historical range in late 2022 early 2023:

The second reason, and probably the one that constitutes the longer-term concern, is fears of a terminal decline in alcohol consumption. Some people view the alcohol industry as the tobacco industry in the 60s. Smoking rates have considerably fallen since:

Tobacco-related stocks, however, did quite well against this backdrop. I am no expert here, but this has probably something to do with (1) consolidation, (2) smokeless products, and (3) lower starting valuations as the market feared the industry was forever doomed.

The fears of a terminal decline in alcohol consumption stem from several sources, but I think we can highlight two: people wanting to live healthier lifestyles and the potential impact of GLP-1s (now widely distributed in the US to treat obesity). My goal with this article is to shed some light on the question…

Is alcohol consumption in terminal decline?

As a spoiler, I must say that I chose the words “shed some light” for a particular reason: the answer to this question will only be known in hindsight. The best thing we can do is examine the evidence we have today. Let’s look at some data.

The argument of the many people who claim that alcohol consumption is in terminal decline tends to be anecdotal evidence (i.e., what’s around them). I’ve found that these people don’t tend to have much real data to back up their claim other than…

The dropping stock prices of alcohol stocks (i.e., “the market is telling you”)

Growth deceleration across the sector

The latter might be a question of destocking, which seems to be reaching the end of the tunnel. I, for example, have not seen much lower alcohol consumption around me, but I am aware that the subset of people I know can’t be used as a proxy for global consumption. Let’s focus on the US, the largest alcohol market by value, where most of these concerns stem from, and from which alcohol-related companies generate a significant portion of their profits.

Gallup recently released a survey where it surprisingly showed that, despite all the headwinds, alcohol consumption remains relatively steady in the US:

On average, U.S. drinkers report that they had four drinks in the past week, which matches the trend average since 1996.

“Bears” or “skeptics” here will point out that the impact of GLP-1s is probably still absent from this data, something that I would agree with but that I will discuss in more detail later.

Gallup’s findings are consistent with those shared by some large companies (not that it’s surprising that these companies say alcohol consumption is not in terminal decline). Destocking seems to have put pressure on sell-in (sales to distributors), but sell-out has remained much more resilient, albeit dropping from pandemic highs.

Consumption is also not evolving uniformly across the different types of alcohol. Spirits are gaining share of wine and beer (not necessarily in volume but most likely in value), probably taking advantage of the trend of people drinking less but better. So, while this doesn’t answer the question above, it does seem to show that declines might not be as abrupt as many believe them to be (at least for now). What the future brings is an entirely different topic, but the notion that significantly less alcohol has been consumed in the US over the last couple of years seems inconsistent with available data.

Now, enter the two horsemen of the apocalypse: the Surgeon General of the US and GLP-1s. Let’s start with the former. Last week, the Surgeon General of the US came out with the following advisory note:

At first glance, it seems like an eye-grabbing headline and it’s no surprise that it caused sector-wide declines. The most eye-grabbing part of the news was probably the recommendation to include cancer warnings on the labels of alcohol products (just like you can find in tobacco products). The only caveat here is that this change needs to be approved by Congress, and alcohol consumption does not seem to be what Congress is currently worried about. Even if these labels eventually make it to the bottles, we not only have to think about what it might do to demand but also to supply (discussed in more detail later).

Before rushing to conclusions, we should understand where the Surgeon General’s concerns come from. Alcohol consumption recommendations are issued in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA). The DGA currently establishes that Americans should drink moderately, moderately being no more than 1-2 drinks per day on days alcohol is consumed. This recommendation is lower for women (no drinks or 1 drink), and you’ll soon understand why.

The DGA asked the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to review the evidence that moderate alcohol consumption is bad for health. The report came out earlier this year, and I should note that it’s not a new study but rather a summary of a collection of studies that have already been done. As you might have correctly imagined, these studies are not perfect and, therefore, should be taken with a grain of salt.

The report evidently supports the General Surgeon’s view: alcohol consumption can indeed increase the probability of cancer. However, the evidence is not as strong as the General Surgeon’s words would suggest. The only clear link between moderate alcohol consumption and cancer lies in breast cancer. This is already considered in the DGA’s current recommendation, as recommended quantities are lower for women. As for other types of cancers historically related to alcohol consumption…

The committee determined that no conclusion could be drawn regarding an association between moderate alcohol consumption and oral cavity, pharyngeal, esophageal, or laryngeal cancers.

But there’s even good news in the report. It claims that moderate alcohol consumption can even have beneficial impacts on one’s health:

There was a 16% lower risk of all-cause mortality among those who consumed moderate levels of alcohol compared with those who never consumed alcohol.

One can be skeptical about these studies (and rightly so), but there seems to be a clear difference here between alcohol and tobacco: while there’s no doubt that tobacco is harmful to one’s health, there seem to be reasonable doubts regarding moderate alcohol consumption. Another reason why I would not compare tobacco and alcohol is that alcohol companies are already transitioning to no/low alcohol products. Contrary to what many people think, there’s more to these companies’ moat than brands and aging; there’s also distribution which is a significant entry barrier in geographies like the US. Something else to consider related to these endeavors is that they will probably not be subject to excise taxes and, therefore, can potentially be more profitable for these companies.

Another interesting thing the report points out is that it’s very tough to measure the impact on our health from the social settings in which alcohol is consumed, but that these social settings are likely to be beneficial for our mental health.

All this said, the data doesn’t matter as much as the perception here, so we should definitely understand how society views alcohol consumption. According to Gallup, an increasing number of people view alcohol consumption as bad for their health, especially the younger cohorts:

This is what ultimately matters for alcohol consumption going forward. Two things to consider here. First, as people increasingly view alcohol as bad for their health, they might shift to drinking less but better (i.e., shifting to spirits). Instead of drinking 4 or 5 beers, people might opt to sip a cocktail instead. Data from Gallup also seems to support this, as spirits consumption has been on the rise for some time:

Secondly, we should also ask ourselves what this negative publicity can do to supply. Many celebrities have jumped onto the bandwagon of launching their spirits brands (Diageo acquired Casamigos from George Clooney, for example). With alcohol increasingly being seen as unfavorable for society, one can only wonder what this might do to celebrity-sponsored brands. A situation where demand falls slower than supply might not be bad for incumbents in terms of share gains, even if these share gains come from a shrinking pie (still TBD).

Enter GLP-1s. GLP-1s, previously used to treat diabetes and now used to treat obesity, have been increasingly linked to lower alcohol consumption. Studies thus far have only been performed on animals, but there seems to be some evidence that GLP-1s can potentially reduce alcohol cravings. Several things to consider here. The first is that we are still early on the GLP-1 curve, and therefore, current data is not the best and tends to be mostly anecdotal. The second thing to consider here is that many people stop taking GLP-1s not long after their initial doses:

Only 47% of patients were still taking a GLP-1 at 180 days; 29% at one year; and 15% at two years.

The impact that temporary GLP-1 consumption can have on permanent alcohol intake is unknown and is something that we’ll only know in hindsight, but it doesn’t seem to be a white/black scenario but more of a grey scenario. I would also argue that many people who drink moderately do so not due to their craving for alcohol but due to socialization. So, there’s simply no answer today to the question: “Will GLP-1s terminally decrease alcohol consumption in the US?” Consuming alcohol is definitely not recommended while taking GLP-1s, but as I’ve shared before, rarely do people stay in GLPs for long.

The third and probably most important thing to consider is that mass distribution of GLP-1s is unlikely to impact emerging countries where the largest spirits companies have already positioned themselves. The US is an important geography for most spirits companies, but it’s definitely not the only one. For example, Diageo derives around 39% of its sales from North America (although 50% of its operating profit). The reason Diageo’s margins are higher in North America than in other geographies is that it’s a more premiumized geography, which is arguably something that should also happen to emerging economies as the middle class grows more prominent.

GLP-1s are unlikely to have the same impact outside North America for several reasons…

The obesity problem is not as widespread: in the US, around 43% of adults have obesity, compared to 16% worldwide (the worldwide number includes the US number, so it’s arguably lower ex-US)

GLP-1s are expensive, and many people in emerging countries can’t afford them

All this said, the impact of GLP-1s on alcohol consumption is a TBD, but it’s definitely something to keep an eye on. What I would be wary of is taking some of the data at face value. For example, there’s a study that claims that after analyzing social media, around 71% of GLP-1 takers have seen their cravings reduced:

In the social media study, we report 8 major themes including effects of medications (30%); diabetes (21%); and Weight loss and obesity (19%). Among the alcohol-related posts (n = 1580), 71% were identified as craving reduction, decreased desire to drink, and other negative effects.

The only problem is that there is an evident selection bias, as people who don’t see reduced cravings are unlikely to post about it on social media.

For all that I’ve discussed above, I believe that it’s still soon to call a terminal decline in alcohol consumption, especially a global one. The impacts of GLP-1s on alcohol consumption sure seem promising, but there are no numbers yet to back the theory up. Even if we look at company numbers, we can see that, while weak, these companies have not done as badly as their valuation drops portray. Diageo’s organic sales dropped 0.6% in FY 24 after strong years during the pandemic and destocking in Latin America. Brown Forman’s revenue remains close to an all-time high:

What seems clear is that there’s a disconnect between valuations and fundamentals (at least compared to history), meaning that sentiment is playing a relevant role here. Any hint of reacceleration could translate into a sentiment change, but this is also TBD.

There are also arguments in favor of the sector deserving structurally lower multiples going forward. Organic growth might not be as high in the future and investments into aging inventory might put downward pressure on cash conversion (just thinking out loud here).

Anyways, I am well aware I might be pretty biased in my analysis. Even though I have tried to remain as objective as possible when searching for data, all humans are biased to some extent, and I don’t think I am different. If you have a different view or would like to share other interesting data that contradicts (or supports) my view, please leave it in the comments section.

In the meantime, keep growing!

This was an enjoyable read, Leandro. Plenty of parallels to the tobacco industry, as well as pockets of deep contrast.

"Tobacco-related stocks, however, did quite well against this backdrop. I am no expert here, but this has probably something to do with (1) consolidation, (2) smokeless products, and (3) lower starting valuations as the market feared the industry was forever doomed."

This is simplified but correct. Legislation and regulations aimed to reduce usage over the last 70 years have been based on perceived health harms to the individual and society. However, restrictions on marketing and advertising made it ever more difficult for new brands to enter the market. Over time, consolidation naturally occurred. Reduced marketing and advertising spending provided excess capital to reinvest, either internationally or into diversification efforts (almost all of which were terrible.) Perhaps most importantly, widespread pessimism has been a massive driver of profitability. Both outsiders and the industry itself had long underestimated the long-term demand for tobacco. A consolidated industry was able to exercise tremendous pricing power over time. And, as you said, low multiples led to staggering returns. That was also amplified by capital used to repurchase shares, which were often priced as if the industry was going to rapidly disappear entirely.

Plenty more to say on smokeless, other categories, and now next-gen products, which I write on a fair bit. But a great resource to learn more about the widespread pessimism that has seemingly always existed against the industry is an interview we conducted with Rae Maile, a veteran analyst who has covered the industry for more than 35 years:

https://www.preferredsharespodcast.com/p/rae-maile-a-lifetime-in-tobacco

I'd be hesitant to take much from the animal studies. The vast majority of people do not drink because they have cravings - they do so because they enjoy it, or because it reduces their social anxiety. To me, increasing awareness of alcohol's effects on health is a much bigger issue than GLP-1s.