I will trim ASML when it gets to this price

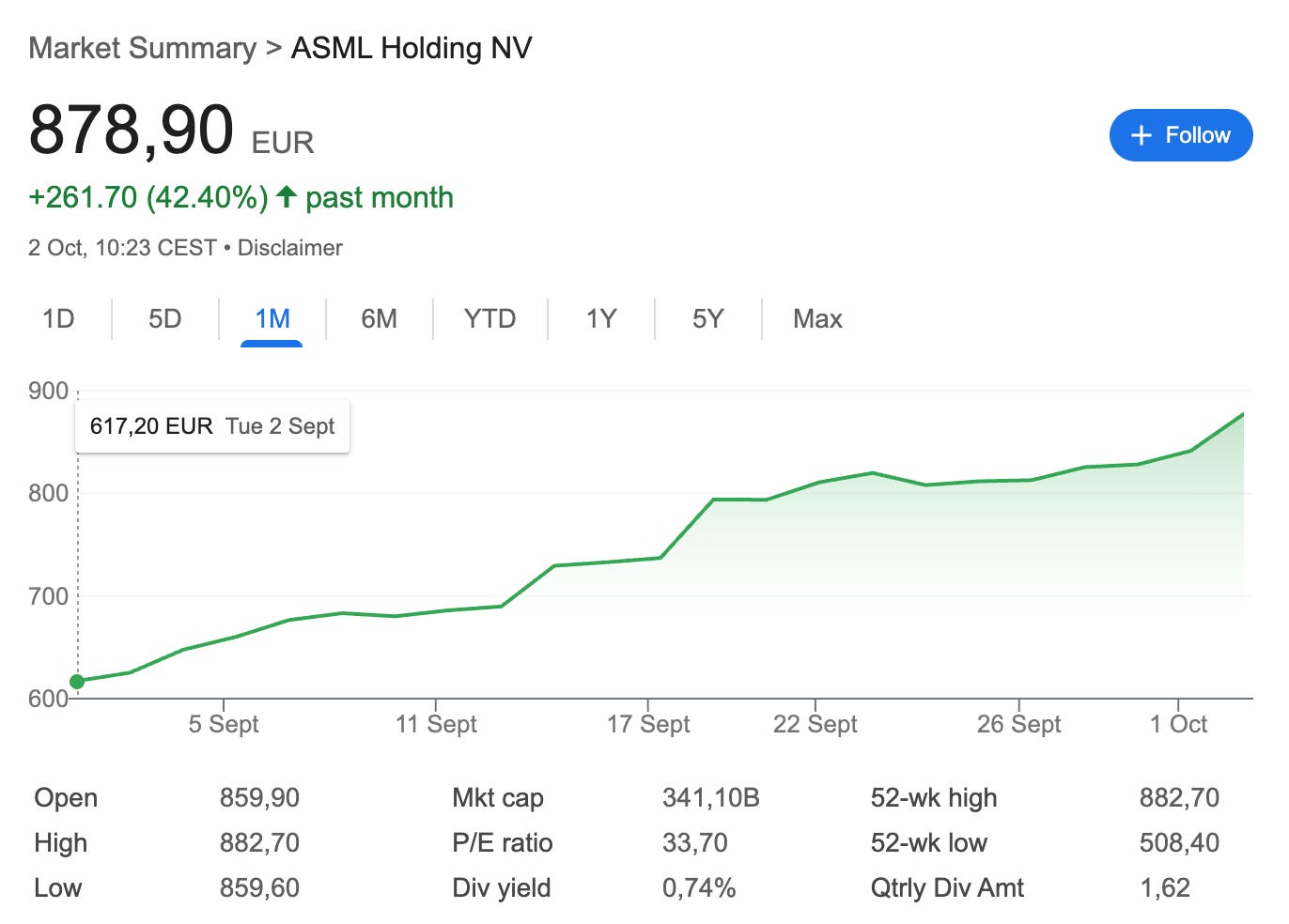

The last time I wrote about ASML (‘ASML’s China Risk’), the stock was trading at roughly €647. Pop up a chart of ASML’s stock today, and you might be surprised to see it trading just under €900. A +40% jump in just under a month:

Although a 40% rise in such a short period may give some people vertigo, the reality is that ASML was not trading at a multiple that a company of its quality, growth profile, and defensibility should. I believe many were well aware of the company’s key role in the semi supply chain (I don’t claim to be alone), but something seemed to be holding back the stock: several “headwinds,” the market’s obsession with timing inflections, and the subsequent narrative that was formed around both of these things (remember that narratives always follow price).

I can think of a few reasons why ASML was not enjoying positive investor perception (it’s also worth noting that a stock that is down 40% from its highs and trading at a market multiple is not consensus because you’ve seen a couple of posts on X):

Geopolitical uncertainty causing a deferral of orders. This led ASML’s management to claim that they could not confirm 2026 as a growth year

Intel’s and Samsung’s “fall,” turning TSMC into a potential monopsony for high-NA EUV. The rationale was that monopsony power provided TSMC with significantly more leverage when ordering systems from ASML (interestingly, not many people thought about the leverage it gave TSMC over other providers, which in most cases are not the sole source of their respective technologies)

The belief that litho intensity will go down in the coming years as etch and deposition are increasingly used in new nodes (3D structures)

Some people’s belief that China will come up with a credible DUV/EUV competitor soon

While some of these concerns were (and still are) valid, we’ve recently received new information that may have contributed to an improvement in sentiment. Let’s briefly go over these one by one and in order.

1) “Geopolitical uncertainty causing the deferral of orders.” Pretty much everyone knew this would most likely be temporary, but many still remained on the sidelines, waiting for the inflection. Although we won’t know until October 15th (Q3 earnings) whether ASML has received new orders, several developments may indicate that these have already arrived. The first is that the tariff uncertainty TSMC discussed as the reason for their cautious Capex has been resolved, and the company remains at its highest capacity in years. The second one is that several insiders bought stock in the open market for the first time in at least a decade.

2) “Intel’s and Samsung’s fall, turning TSMC into a monopsony.” I believe it should be pretty obvious by now that the US government is not interested in letting Intel fall. The competitive environment in the foundry business is poised to heat up over the coming years, which is excellent news for ASML. I’ll list some positive developments here, in no particular order: AMD potentially becoming an Intel foundry customer, several customers willing to build test chips in Intel’s 14A process, the NVDA partnership and investment (although not foundry-related), which probably reflects the US government’s intentions…

On the Samsung side, Tesla has signed a long-term partnership with the company worth $16.5 billion for advanced chip manufacturing, and several other rumors have surfaced about 2nm wins.

While all of this doesn’t mean Intel and Samsung have automatically become credible competitors to TSMC, it does mean there’s a chance. This GIF seemed well-suited for this occasion:

Some months ago, people believed that TSMC’s monopoly would last forever, but it seems that geopolitics really don’t want this to be the case.

3) “The belief that litho intensity will go down in the coming years.” While litho intensity may ultimately decrease in the future (ASML thinks otherwise), I believe there are two key considerations to consider. The rationale here is that when NAND transitioned to 3D, litho intensity dropped considerably in favor of other steps, such as deposition and etch. With DRAM eyeing a similar (but more challenging) transition to 3D, will litho intensity and therefore high-NA adoption suffer the same fate? Some rumors suggest that memory foundries like SK Hynix are eyeing a significant EUV capacity expansion and that EUV layers at memory customers will increase going forward. To this I would add that it’s not so much about market share but about value capture (I’ll explain this in more detail below)

4) “Some people’s belief that China will come up with a credible DUV/EUV competitor soon.” Touched on this topic in depth in the article ‘ASML’s China “Risk”’

Even though some of these concerns were and still are undoubtedly valid, the reality is that the valuation mostly captured all of them when ASML was trading at a market multiple. The chances one gets to buy a monopoly in one of the most critical industries in the world are few and far between. Many people kept claiming that ASML would be a share loser due to a decrease in litho intensity, but the litho premium (the valuation differential between ASML and the rest of semicap) had mostly dissipated. With most of semicap enjoying excellent performance lately, the gap has not widened significantly either despite the run. The litho premium remains in check.

The monopsony argument remains valid, but I like to think about it in terms of value capture. ASML is a monopoly, and regardless of whether TSMC has monopsony power or lithography intensity decreases, the company is well-positioned to capture its fair share of the value (this is what makes monopolies attractive). While most of semicap is oligopolistic and enjoys strong competitive positions, there’s no denying that their position in each of the bear cases above (except in the litho intensity part) is objectively worse than that of ASML. It’s far easier for China to mimic their technology (albeit not easy); they were also impacted by capex uncertainty, and they suffer from TSMC’s monopsony power to a greater extent by not being the sole-source. By the way, I’m not dunking on semicap; I think it’s a great industry.

So, with the stock up so much in such a short period, it’s worth asking ourselves:

What’s the right price to trim?

I plan to address this question later in the article, but let me first explain why I’m discussing trimming in the first place.

My previous mistake with ASML (it still stings, although it’s very easy in hindsight)

Those of you who’ve been following my work for a while will know that I round-tripped ASML in the past. I went from a 110% gain in under two years back to flat (currently up around 60%). ASML was trading back then at a somewhat hefty valuation, significantly above where it is today:

So, what made me avoid selling back then despite the hefty valuation? The false belief that ASML has optionality. Now, let me explain this properly. I do believe that ASML has significant long-term optionality. Peter Wennink (former CEO) explained it best during the 2022 Investor Day:

We simply cannot connect all the dots. And those dots are being created because the value of Moore’s Law is there. We’re creating more value than we ever thought possible.

The semiconductor industry enjoys a virtuous cycle. Every technology innovation drives more chip demand and makes the next technological innovation unknown and unforecastable (who knows what AI will allow us to do!).

Now, the problem with assuming that ASML has short- to medium-term optionality (and therefore that 2030 guidance can be significantly higher than forecasted) is that we would be assuming that supply can expand quickly, which is not the case. In short, ASML doesn’t have a problem of demand; it has a “problem” of supply, and it’s the demand that creates short to medium-term optionality. Companies like TSMC and Nvidia can enjoy an immediate revenue increase by implementing significant price increases and maximizing utilization. This is the reason why they have been direct beneficiaries of the AI wave.

The case for ASML is a bit different. First, system orders tend to come with a lag as customers wait to ensure they need more capacity before committing to capital expenditures (Capex). Secondly, building an EUV system requires a significant amount of firepower, capacity, and time, so ASML can’t simply come up with new capacity immediately. This means that, while there might be optionality in guided numbers, this is likely to come from IBM sales more than equipment sales (perhaps this is a good topic for another article).

So, the bottom line is that ASML has optionality, but that the timing of said optionality also matters. Despite the fact that ASML doesn’t have much short term and medium term optionality due to its capacity constraints, I also want to briefly explain why I am now more open to trimming or “trading” around my positions (albeit I don’t expect to do this regularly). I recently wrote the following in a post on X:

Think that it’s important to remain self-critical as an investor, so here’s a shot at it (have been thinking about writing long form about it):

The good: think I’ve been relatively good at the research in general and spotting opportunities. I am not looking for 10x (although I sure welcome them) and I think I’ve found a good balance between risk and return (I’ve obviously made mistakes as they are part of the game)

The bad: think I have to improve quite a bit in terms of position sizing. I’ve been relatively good at sizing up positions (maybe not enough) but terrible at sizing them down when the risk/reward was not favorable. This has cost me performance and have to get better at it

One of the challenging things about investing is that mistakes seem obvious and are easy to spot in hindsight, but it’s tough to change our behaviour while making one.

ASML was my top 2 position before the recent run (currently my largest position), but the risk/reward relationship gets worse as the price rises (considering that nothing fundamental has changed here, mostly sentiment), so I think it’s reasonable to trim positions when this happens. The downside is that one faces taxes when selling, the upside is through this method one can potentially maximize the expected IRR of their portfolio. There’s a prerequisite to implementing this strategy, however. One must have a clear idea of what a business is worth or, better said, what they are willing to pay for something. Only this way can one understand when the risk-return is favorable and when it’s not. I truly believe that if one buys a great company, the moment to sell is almost never, but this doesn’t mean that one shouldn’t manage weights inside the portfolio. All this said, I expect to do this infrequently.

So, now the key question…