How To Differentiate From The S&P 500

Before jumping directly into today’s (free) article, I would like to do something I rarely do: recommending directly another investing blog: The Wolf Of Harcourt Street.

I’ve known Wolf for quite a while and he provides some impressive work on companies like Evolution, Adyen, Nu…and many others. There are not many people actually delivering deep research, but Wolf belongs to the rare breed. I believe great work deserves visibility, so I would highly recommend subscribing to his blog:

Hi reader,

Index ETFs (and all sorts of other ETFs) have enjoyed great success over the good part of the last two decades. This success has not been undeserved, considering they offer a relatively simple and inexpensive way of gaining exposure to the best wealth-creation machine in history: the stock market.

Another benefit added to simplicity and cost has been performance. As you might also know, indices have also seen great success performance-wise, with many research papers quoting that north of 90%+ of active asset managers don’t beat the index over the long term. While this stat definitely seems scary when embarking on a journey to pick individual stocks, I’d argue that individual investors have a clear edge compared to professional managers, an edge which interestingly stems directly from the indices themselves. This edge comes from individual investors not needing to justify performance yearly and, therefore, not needing to compare their performance to that of the indices (or benchmarks) like professional investors do over the short term (or even over the long term). This is a topic for another article, but in today’s article, I wanted to talk about a “flaw” that indices such as the S&P 500 have that not many people might be aware of: float-adjusted weights. This flaw ultimately allows investors to differentiate significantly from the index.

What are float-adjusted weights?

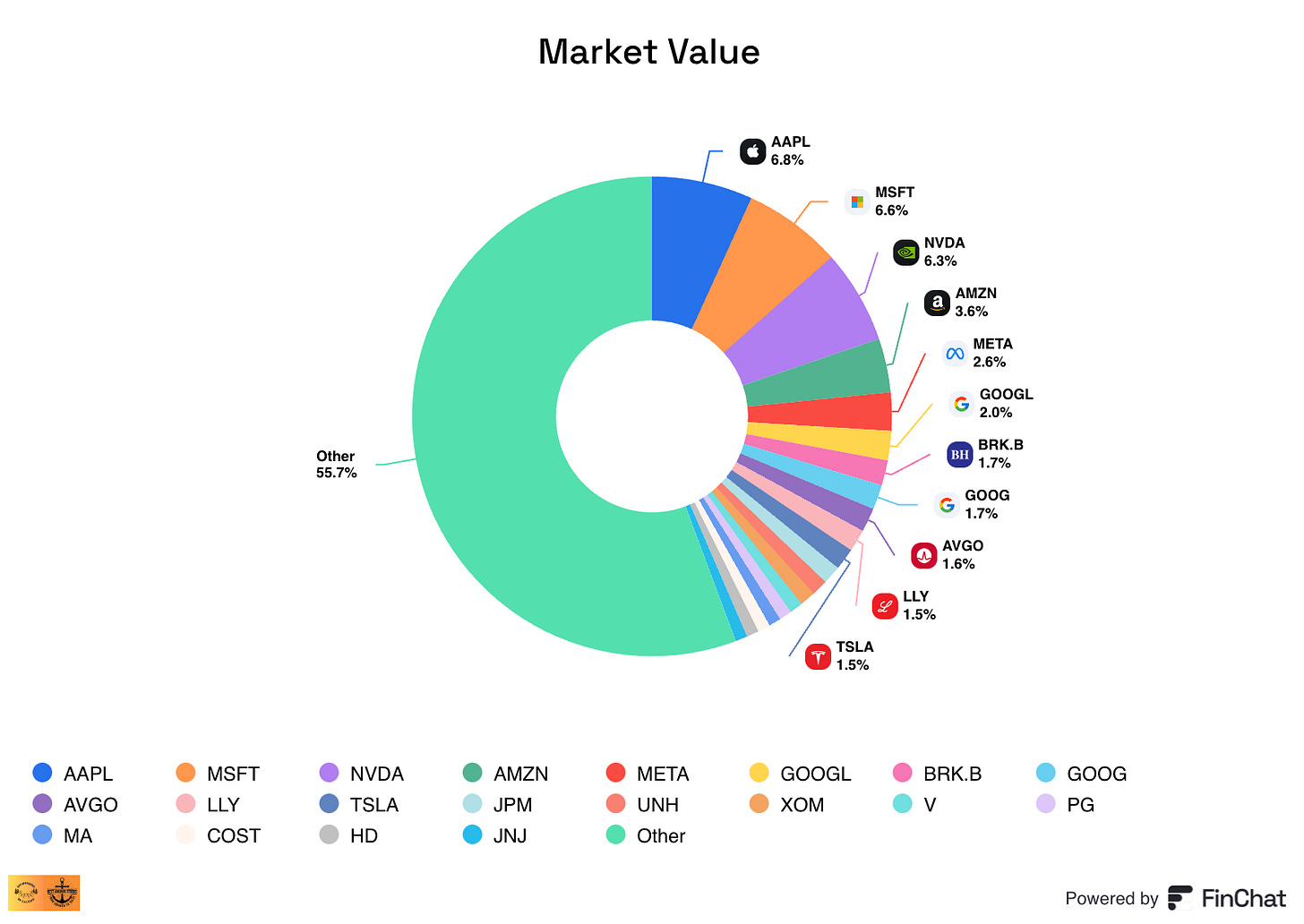

Many people are aware that the S&P 500 (like most other indices in the world) is market-cap weighted. This basically means that the weight of any given company in the index is determined by the market cap of that company relative to the total market cap of all its constituents. As tech companies have become larger and larger, they’ve gone on to dominate the leading world indices. Just for context on how concentrated the current indices are, take a look at the following stats…

The top 20 holdings of the S&P 500 make up around 45% of the index, with the remaining 55% being comprised of more than 450 companies

The top 10 holdings of the S&P 500 make up around 35% of the index

While many people will be unaware that by investing in the S&P 500 they are putting 45% of their money in 20 companies, most are aware that larger companies will weigh more in the index than smaller ones. With the exception of the Dow (which is price-weighted), most indices work this way.

What not many people are aware of is that market-cap weighted indices are typically also float-adjusted. This means that weights are adjusted down to take into account the free float (i.e., the portion of the outstanding shares that are really “tradeable”). S&P Global will adjust the weights of the different companies included in the S&P 500 by multiplying them by what they call an ‘Investable Weight Factor.’ This factor is simply calculated by dividing a company’s free float by the total number of shares outstanding. But what do they exclude from the free float? S&P Global gives a list of what’s excluded in what they refer to as strategic shareholdings. As you can see below, strategic shareholders are (in most cases) the type of shareholders than any long-term investor would like to see:

Shares held by the following types of shareholders are excluded regardless of whether the particular shareholder intends to exercise any form of control.

Long-term strategic shareholders generally include, but are not limited to:

Officers and Directors (O+D) and related individuals whose holdings are publicly disclosed

Private Equity, Venture Capital & Special Equity Firms

Asset Managers and Insurance Companies with direct board of director representation

Shares held by another Publicly Traded Company

Holders of Restricted Shares

Company-sponsored Employee Share Plans/Trusts, Defined Contribution Plans/Savings, and Investment Plans

Foundations or Family Trusts associated with the Company

Government Entities at all levels except Government Retirement/Pension Funds

Sovereign Wealth Funds

Any individual person listed as a 5% or greater stakeholder in a company as reported in regulatory filings (a 5% threshold is used as detailed information on holders and their relationship to the company is generally not available for holders below that threshold).

There must be at least 5% of the float in strategic shareholders for the weight to be adjusted. This means that if insiders hold 3% of the stock and there are no further strategic shareholders then the float is not adjusted. However, if insiders own 3% of the outstanding shares and there’s an additional 5% strategic shareholder, then the full 8% (3% + 5%) is taken into account in the Investable Weight Factor.

We could look at the example of Amazon to put some numbers to this. Let’s assume that Amazon’s only strategic shareholder is its insiders. The company’s insiders own around 9% of the outstanding shares (Jeff Bezos, mainly), so the Investable Weight Factor would be 0.91, which would be multiplied by the market cap weight to end with the true weight of Amazon in the index. This means that, all things equal, a company with no strategic shareholders and the same market cap as Amazon would weigh 9% more than Amazon in the index. This, in my opinion, portrays the main flaw of the indices and how individual investors can differentiate.

What the indices underweight and why it matters

Based on the explanation above, it should’ve become pretty clear that most market-cap weighted indices underweight owner-operator companies. Owner operators companies are companies where the founders/insiders remain at the helm, in most cases through significant stock ownership. The index will underweight these companies because, by definition, those significant stock ownerships will not count as float and therefore their market caps will be adjusted downward. For the sake of this article, let’s go with an extreme example: Hermes. (Remember you can read my deep dive on the company here.)

The Hermes family owns around 70% of the company. This means that if it were included in the S&P 500, it’s market cap weighting would be multiplied by 0.3 (the Investable Weight Factor) to derive its true weight. This ultimately means that the index would be severely underweight Hermes.

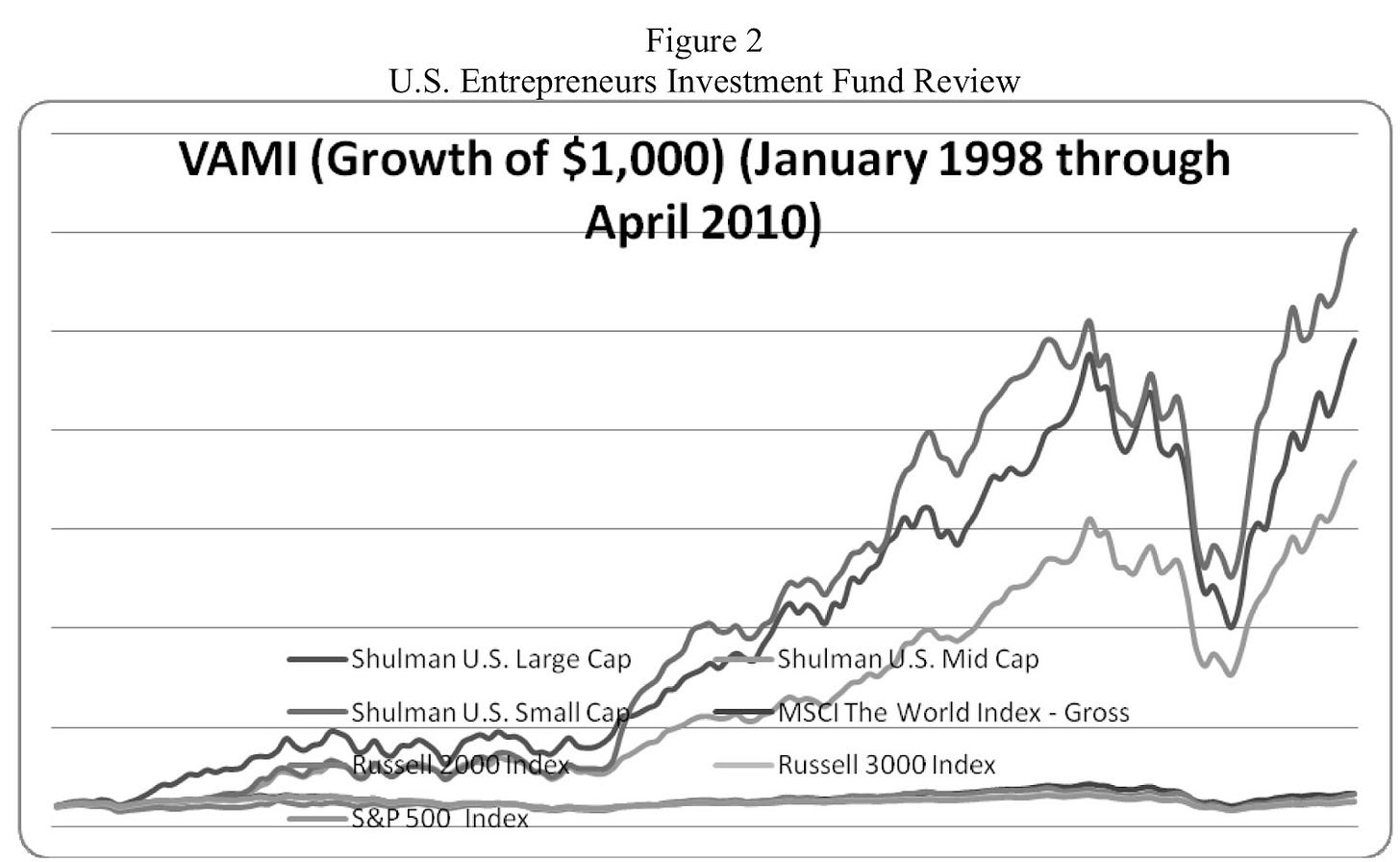

But why is this a “problem” or a “disadvantage”? Well, because several studies show that owner operated businesses tend to outperform significantly their counterparts over the long term. The last study I read was from 2012 by Joel M. Shulman and showed that, from 1998 to 2010, fictional indices built with 288 owner operated companies crushed the indices. When I say “crushed,” I mean it:

And in case you can’t see it there clearly, there’s a quote from the study that is simply breathtaking:

Over the entire period of the study, all three of the entrepreneur index benchmarks dominate the stock index benchmarks by a wide margin. During the 12 year 4 month period, the Small Cap entrepreneurs produce the strongest results, with an increase of 3,000%. Large-Cap entrepreneur portfolios experienced an increase from $1,000 to approximately $25,000 and Mid-Caps had an increase of $1,000 to approximately $19,000. By contrast, all of the key benchmarks including the Russell 3000, Russell 2000, S&P 500 and the MSCI World Index barely changed during the same time period.

Owner-operator firms have not outperformed only in terms of stock market returns but have also outperformed fundamentally speaking (higher ROIC and higher organic growth, on average) and in terms of risk (outperformed with lower financial leverage).

The past is never a perfect proxy of the future, but the reasons that created the outperformance in the past are alive and well today. Owner-operators are more aligned with shareholders, think longer-term (because they can without being fired), and think much more about durability. It’s hard to believe who thought it would be a good idea for the S&P 500 index to be underweight these companies, but it is and it’s something that individual investors can use to differentiate. There’s a high probability that a portfolio made up of owner-operator businesses would…

Be remarkably different to the S&P 500

Would be pretty high quality (assuming the company is great)

But the “momentum” factor makes it even worse…

The adjustment methodology makes it even worse

S&P Global periodically adjusts the weights of the S&P 500 to take into account changes in the Investable Weight Factor. This means that owner-operator companies that have been retiring shares (ie., making buybacks) will weigh even less once the adjustment occurs. The reason is that, by retiring shares, the ownership of the strategic shareholders increases (assuming they have not sold or tendered their shares for the buyback) and therefore the Investable Weight Factor decreases.

Let’s go with an example. Say that a company has 1,000,000 shares outstanding, 100,000 of which are owned by insiders. This means that the Investable Weight Factor is 0.9 (discounting the 10% ownership). If management decides to retire 10% of the shares outstanding, the Investable Weight Factor goes down to 0.89 automatically because insiders now own 11% of the company (100,000/900,000). Of course, the immediate impact is not large, but if a company substantially reduces its shares outstanding over the long term without a change in the ownership of strategic shareholders, then the adjustments can be material and that company would weigh less and less (relatively speaking) as time goes by.

All the above adjustments, in my opinion, make little sense because seeing a company gradually reduce its shares outstanding while strategic shareholders are not selling should be good news.

We also get the opposite. Imagine that strategic shareholders decide to do one of two things, or both…

Issue shares

Sell their shares

Under both scenarios, the Investable Weight Factor would increase because the float would increase relative to the ownership of the strategic shareholders. This means that the S&P 500 would adjust positively for companies that satisfy one of the above, or both. Imagine Jeff Bezos were to sell his entire stake tomorrow. This would be terrible news for long-term shareholders, but Amazon would weigh (all things equal) 9% more in the S&P 500 automatically.

As an individual investor I would probably do the exact opposite in both cases, meaning that I would like to own more of a company retiring shares and high insider ownership than of one diluting shareholders or where insiders are running for the exits.

The businesses also matter, of course

With this article I am not trying to portray that finding an owner-operated business directly translates into spectacular returns. In fact, I’d argue that the great return of the group can be attributed both to great performance to the upside but also to lower failure rate in the downside (recall these firms tends to operate with low leverage). The underlying business matters dearly and plays a key role in outperforming the index over the long term. Investing is all about odds, and if history is any guide, owner-operated businesses seem to increase the odds of beating the index, not only due to their underlying characteristics but also due to how the index treats these.

It’s also worth noting that small and mid-cap companies with low float tend to be out of reach for many funds. Take, for example, a $5 billion business where insiders own half of the business. That means that there’s only $2.5 billion available to purchase by funds, bringing down the amount of money large funds can invest here to move the needle.

Owner-operators in the BAS portfolio

Every time I write an investment-related article, I like to see how my portfolio scores (when applicable) against what I’ve discussed. There are currently 15 businesses in the portfolio. The average insider ownership (note that strategic shareholdings is a more ample term than just shareholders), stands at around 12%, ranging from 70% down to 0% (not really 0, but negligible). This basically means that if an index holds the positions in my portfolio, they would most likely be underweight by around 12% compared to peers with no strategic shareholdings:

If you want access to my portfolio and the research, feel free to subscribe below:

The leading indices have enjoyed great performance despite this “flaw,” so one can only wonder what they would’ve achieved if they would’ve overweighted owner-operated businesses.

In the meantime, keep growing!

How can one buy an S&P 500 fund and adjust Tesla's weight to 0% in it?

The Shurman study sounds interesting, though given how extreme the results are it feels like they must have (either consciously or subconsciously) picked companies that performed better in hindsight, not just on the basis of owner-operation. Do you have a link to a pdf? Can't seem to find one that's not behind a paywall.