Free Cash Flow and Bond Yields: Apples to Apples?

The premium subscription gives you access to all the content in Best Anchor Stocks, which includes…

All the deep dives

Recurring articles

Access to my real-time portfolio and transactions

Occasional webinars on various topics

A community of like-minded investors

A subscription the Premium + also gets you a quarterly Q&A with me to discuss anything you’d like.

If you want to know the type of content I share at Best Anchor Stocks you can read the Deere deep dive I uploaded a few weeks ago for free…

…or you can also read any of the other many free articles I have shared, just like this one!

You can also read the testimonials that existing subscribers have left. If you are a passionate and curious investor wanting to learn about high-quality companies, don’t hesitate to join Best Anchor Stocks!

Hi and welcome to a new Best Anchor Stocks blog post,

Many of you might be aware of the financial industry’s “obsession” with comparing free cash flow yields to bond yields to judge whether a stock is over or underpriced. It goes something like this:

(Insert company name) is trading at a 3% FCF yield, with bond yields at 5%, it seems heavily overpriced.

The reasoning is straightforward: stocks should, in theory, offer higher free cash flow yields than bonds to compensate for their “higher” risks. These risks primarily stem from uncertainty, as a business’ path over the next 10 years is typically unknown and offers a high degree of variability. Investors' willingness to be compensated for higher risk is completely understandable, but we must not ignore the caveats. These caveats are important to understand what we are comparing to what and should make us aware of the limitations of this shortcut to valuation.

The first caveat is obvious: Free Cash Flow yields have embedded a certain level of growth, whereas bond yields are static (of course, dynamism can go both ways, as I’ll discuss later on). Bond investors should expect to get their interest payments during the bond's lifetime together with the repayment of the principal at the end. Stock investors, however, should expect to get the current free cash flow yield (this is not always the case, though) but should also expect this amount to grow over their holding period. If everything goes right and the market still expects growth ahead at the selling date, they might even cash out on a higher amount than they paid for.

Just some minor caveats here:

Not all companies return all free cash flow to shareholders, so investors might get less than what belongs to them.

An investor can continue to own a stock for many more years, whereas the lifecycle of the bond is fixed (most of the time).

Terry Smith summarizes the advantages of stocks over bonds with the well-known term “compounding”:

Investment in stocks and shares (equities) has a unique advantage over other asset classes which in my experience is rarely understood and almost never discussed. Equities can compound in value in a way that investments in other asset classes, such as bonds and real estate, cannot. The reason for this is quite simple: companies retain a portion of the profits they generate to reinvest in the business.

The bottom line is that companies can compound earnings by reinvesting into the business. In contrast, bonds can’t reinvest interest payments at high rates of return (I mean, a bond investor can, but it’s not something innate to the asset class). This reinvestment potential is what eventually enables compounding, which not only brings growth but tax-efficient growth. An investor is not taxed when a company retains its earnings and reinvests them into the business. On the contrary, when investors receive interest or rent payments (real estate), they are typically taxed on this income (depending on tax jurisdictions).

A second advantage of stocks over other asset classes is that they take away a considerable decision-making burden from their investors. As long as the company continues to reinvest these earnings at a value-generating return, the investor only has to make one decision: hold. However, when an asset class provides investors with recurring income (which also has its positives), the investor will always face a decision:

Where do I invest it now?

So, recurring income streams are less tax efficient than internally reinvested earnings and put a much more significant burden on an investor's decision-making process.

Anyways, why am I talking about this if I started talking about yields? The reason is that despite free cash flow yields and bond yields being constantly compared in valuation discussions, all of these considerations should be taken into account when assessing the different investment options, and they rarely are. Let’s dig deeper.

Free Cash Flow yields have growth baked in; bond yields don’t

The main reason that investors should not directly compare free cash flow and bond yields is that it’s a misleading comparison (apples vs oranges). As discussed above, Free Cash Flow yields have growth “baked into” them, whereas bond yields don’t. What do I mean by this?

The “consensus” definition of Free Cash Flow is Operating Cash Flow - Capex - Other investments. There are more ways to calculate Free Cash Flow, but I settled for this one:

In ‘Capex and Other Investments,’ companies typically include two types of investments:

Those aimed at growth, aka growth capex.

Those aimed at maintaining the current operations, aka maintenance capex.

This difference is also well known in the financial community but rarely considered when comparing free cash flow and bond yields, and it should be. The thing is that it’s not fair to compare the free cash flow yield (which is inclusive of growth investments) with bond yields that basically don't grow. It would be much “fairer” to compare an adjusted free cash flow yield to bond yields.

This adjusted Free Cash Flow yield should only consider maintenance investments and thus would be the real Free Cash Flow yield the company would enjoy were it not to grow (i.e., were it to be in the same state as a bond). This simple adjustment makes the comparison fairer because no growth is baked on either side, but it obviously takes a bit more work than getting the Free Cash Flow yield from any financial provider.

It’s normal for the best companies to appear outstandingly expensive before making these adjustments. The reason is that great companies tend to generate substantial cash flows but reinvest much of these cash flows back into the business. This means that their Free Cash Flow generation tends to be muted for a long time, masking their “real” free cash flow generation capacity in a steady state (Amazon is probably the best example here). This might be a bit confusing, so let’s go over an example.

An example

Let’s use Copart as an example. Over the last twelve months, Copart has generated around $1.4 billion in Operating Cash Flow and has reinvested around $526 million of this amount into Capex. This means the company has generated around $900 million of Free Cash Flow over the Last Twelve Months. This translates into an EV/FCF yield of around 2%.

Of course, when one compares this against current risk-free bond yields (close to 4-5%), one might be inclined to ask the following question:

Why would I risk owning Copart if I get more today by buying a risk-free bond?

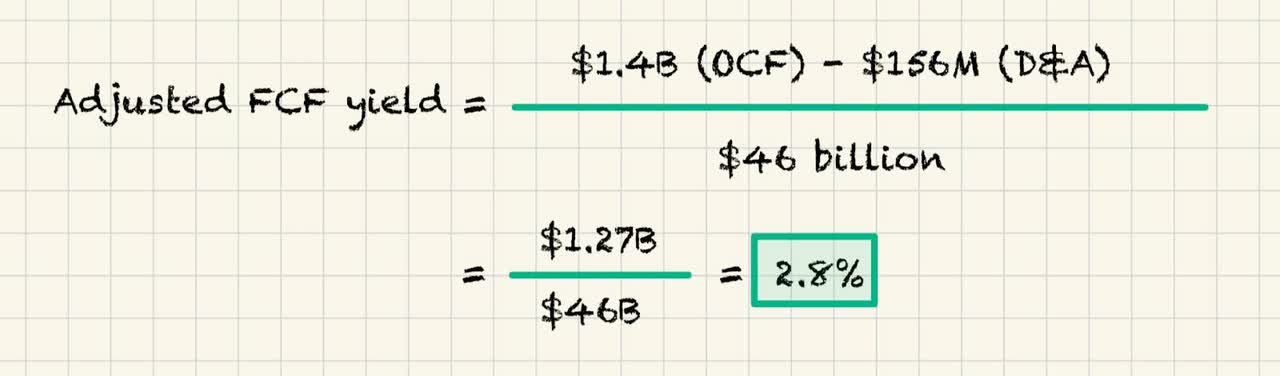

Fair question. Before answering this question, however, one should make the necessary adjustments to make an apples-to-apples comparison. Copart reinvests a considerable amount of its operating cash flow on land to service future expected demand. As land is not amortized and makes up a substantial amount of growth Capex, Depreciation and Amortization (‘D&A’) might be a good proxy for maintenance Capex. Copart had D&A of $156 million over the last twelve months. This means that its no-growth FCF (FCF, which excludes growth Capex) is closer to $1.27 billion. This brings the no-growth Free Cash Flow yield closer to 2.8%.

The fact that Copart invests in advance of demand also means that its margins are not truly optimized, so steady-state operating cash flow generation might also be higher (but I don’t want to complicate things too much).

There’s no denying that a 2.8% no-growth Free Cash Flow yield doesn’t seem cheap either. Still, the objective of this example was not to claim Copart is cheap but to underscore how stark differences can be for businesses that reinvest significantly. Copart’s no-growth FCF yield is around 40% larger than its all-inclusive FCF yield; it’s the former that’s much more comparable to bond yields.

There’s also another caveat for Copart: investments in land not only don’t need to be amortized but tend to appreciate modestly over time. This means that Copart is investing significant amounts not only to capture future growth but also into an appreciating asset, something that’s pretty rare as growth investments tend to depreciate over time and need to be replaced eventually. The main takeaway here is that investors should not focus on how much cash a company is generating but rather on how much cash it could generate if it stopped compounding/growing.

The magic of compounding

Let’s also see what would happen with Copart’s FCF yield if an investor were willing to hold it long-term. Let’s assume the other option is investing in a 10-year risk-free bond offering a 4% yield. If Copart manages to grow its Free Cash Flow at an 8% CAGR over the next 10 years (not easy, but not out of the question for a company like Copart), current holders will see their Free Cash Flow yield on cost go from 2% to 4.2%. This is at a more comparable level than that of the bond yield, which will still be producing the same yield in year 10 as in year 1.

Also, note that this 4.2% free cash flow yield is the all-inclusive cash flow yield. Assuming that maintenance Capex remains at 17% of Free Cash Flow, this would mean that the no-growth Free Cash Flow yield goes up to 5%. This is the one that’s more comparable to the bond yield in year 10. Of course, using these numbers, Copart does not seem cheap either at these prices, regardless of how one puts it (assuming an 8% FCF CAGR). Despite enjoying a no-growth Free Cash Flow yield above the risk-free rate yield in year 10, there’s a lot that can happen over the next 10 years for Copart. On the contrary, there’s a high probability an investor will receive their 4% bond yield at the end of the period. Visibility matters and I’ll discuss this a bit more later.

The only caveat here is that there’s also a lot that can go right for a business over this time frame, rendering our assumptions highly conservative. On the contrary, there’s zero upside to future numbers in the case of the bond yield, so an investor should judge whether the potential upside to their numbers is worth the lower visibility.

What’s cheap and what isn’t cheap?

My example above did not try to portray Copart as cheap/expensive at these levels. Full disclosure: it’s been a long time since I added to my position, and I await better opportunities. The example aimed to provide a framework to make free cash flow yields more comparable to bond yields, or to at least understand the limitations behind those comparisons. But this begs the question…

What’s cheap and what isn’t cheap?

You probably guessed the answer: it depends. The example above should have at least convinced you against automatically categorizing a company as expensive if its all-inclusive Free Cash Flow yield is below the risk-free bond yield. So, what other variables should we consider? There are several, and the “bad news” is that few are quantitative.

The first one is obviously growth. A company might have a meager free cash flow yield but might be expecting strong growth in Free Cash Flow in the coming years. This growth might result from high top-line growth or a return to a more normalized margin/investment cycle. A good example here would be Amazon. Many touted the company’s high P/E or lack of Free Cash Flow as the reason behind the company’s overvaluation. We’ve now seen that Amazon was, in fact, cheaper than many believed, but it wasn’t going through a normalized environment. Of course, its all-inclusive FCF yield is still low, but there are reasons to believe it will expand materially in the coming years.

The second point to consider is risk. Logic would tell us that if a company is much riskier than its counterpart, we should be willing to pay a higher premium over the bond yield to consider it an investment. This means that if we are technically buying a lower-risk company, we should require less of a premium to the bond yield. But, how do we judge the premium differential? Well, that question has no straight answer and depends on qualitative analysis and every investor’s views. Risk is real in the stock market, but the problem comes from risk not being easily measurable. I have no doubts that volatility is not a good proxy for risk, but I have never found a quantitative metric that’s a good proxy, either.

We could understand risk as a higher probability of permanent capital loss and higher variability of future outcomes. It’s pretty obvious that if we can “estimate” the future of any given company with a higher degree of probability, then that company should be worth more than one where the outcome is very uncertain. The main reason here is that such companies get the good part (to an extent) of the bonds (visibility) and the good part of stocks (compounding).

Conclusion

What’s the conclusion of this article? One that I have reached too many times: there’s no shortcut to valuation because numbers don’t tell the whole story. This said, I hope the article was helpful in understanding when we are comparing apples to apples or when we are comparing apples to oranges and the variables we need to consider to make an informed decision. Like in everything that’s investment-related, this decision will remain completely subjective.

The financial industry has always struggled to make investing an objective endeavor despite spending billions. Why? Because investing is inherently subjective for several reasons:

Companies are impacted by their employees and their decisions. They are human beings, not robots.

A view of the future is required, and while the future will inevitably be full of numbers, these numbers will always depend on qualitative factors.

I don’t expect the financial industry to stop trying, but I think investors are one step ahead if they understand how subjective investing is and try to thrive in an uncertain world by focusing on what truly matters.

If you like this content don’t hesitate to join Best Anchor Stocks. There’s a 2-week free trial:

In the meantime, keep growing!