The premium subscription gives you access to all the content in Best Anchor Stocks, which includes…

All the deep dives

Recurring articles

Access to my real-time portfolio and transactions

Occasional webinars on various topics

A community of like-minded investors

A subscription the Premium + also gets you a quarterly Q&A with me to discuss anything you’d like.

If you want to know the type of content I share at Best Anchor Stocks you can read the Deere deep dive I uploaded a few weeks ago for free…

…or you can also read any of the other many free articles I have shared, just like this one!

You can also read the testimonials that existing subscribers have left. If you are a passionate and curious investor wanting to learn about high-quality companies, don’t hesitate to join Best Anchor Stocks!

Hi reader,

Many of you might know (because I have discussed it several times) that my investing philosophy has changed a fair bit since I started investing in individual stocks. I believe I have followed a somewhat normal path where I have gone from buying bad companies that appeared to be cheap to buying companies that seemed to have great growth prospects but were pretty expensive. Finally, I have settled into the investing strategy that suits me best: quality growth investing. My goal is to look for quality companies with significant, durable growth ahead while being patient to buy them when they are out of favor.

Of course, these companies always seem to trade at apparently rich multiples, but if I have learned something in my transition from low PE stocks to high PE stocks, it is that the PE in isolation says very little about a company’s valuation. This is one of the reasons, by the way, why I always ignore valuation metrics when I screen for companies that might be interesting. First, the multiple might be very misleading, and I might miss companies where the normalized multiple is widely different from the reported multiple. Secondly, I prefer to analyze companies regardless of valuation because it helps me remain objective, and I also get to do the homework beforehand (i.e., not in a rush).

Ironically, many investors who claim value and growth are tied at the hip (like Warren Buffett famously coined) are those who later screen using valuation ratios. If they truly believed that value should never be seen independently of growth and quality, they would never include valuation metrics on their screeners.

Anyway, this article doesn’t aim to talk about this topic. The article aims to discuss durability, one of the most important topics when purchasing apparently richly valued companies. I’ll touch on several topics throughout the article, explaining how durability has shaped my investment philosophy and why I think it can generate great returns over the long term. First, let me explain why durability matters, especially in the quality growth arena.

Why durability matters for apparently richly valued companies

Some time ago, I wrote an article titled ‘Quality and Why It’s Often Undervalued’ where I shared the following image:

The image basically shows how most of the value of any given company is located from year 2 onwards, where fewer people seem to focus. On the contrary, very little of a company’s value lies in the next two years, despite many market participants focusing precisely on that investment horizon (for reasons I’ll later discuss). Logically, at higher valuation multiples, the future becomes increasingly important because most of the value of a company will be encapsulated in what the industry refers to as the terminal value.

Suppose we pay a rich multiple (compared to the index) for any given company. In that case, we must be reasonably confident that the outer years will look good regarding competitive advantages and growth, or else we will be in for a terrible surprise.

Note that many people claim that when investing in apparently richly valued companies, your margin of safety is much smaller than when investing in seemingly cheap companies. While the rationale makes sense on the surface, the reality is that the margin of safety will always come from the relationship between the business and its price, not by just one of these two metrics. In short, durability is very important for apparently richly valued companies because the outer years have a more significant weight on the valuation.

Why durability matters for both short and long-term investors

Durability is a topic mainly discussed in the context of long-term investing, but I believe it should matter dearly for any investor, irrespective of their investment horizon. The reason lies in how the market prices future expectations.

A company’s stock price moves based on two variables:

Fundamentals (the E or Earnings)

The value the market ascribes to those fundamentals (the P/E ratio)

Fundamentals are somewhat straightforward to understand, but many sub-variables play a role in determining the value the market ascribes to those fundamentals. There are tens of sub-variables, ranging from macro, to industry-specific events/characteristics, or company-specific news/characteristics. The rationale behind this is that the same level of earnings is not worth the same in every context, something that makes sense. (I wrote an article touching on this topic: ‘The PE ratio: Not All Growth Is Created Equal.’)

One of the sub-variables here, which is typically overlooked but has a significant weight, is durability. All things equal, the market will set a higher/lower valuation ratio for a company depending on how it perceives the durability of the business. This makes sense, right? Suppose market participants believe in a longer duration for a given company. In that case, they will most likely be willing to pay more for the cash flows in the outer years than they will for a company for which durability is in question. The main rationale is that durable companies' probability of enjoying those cash flows is higher.

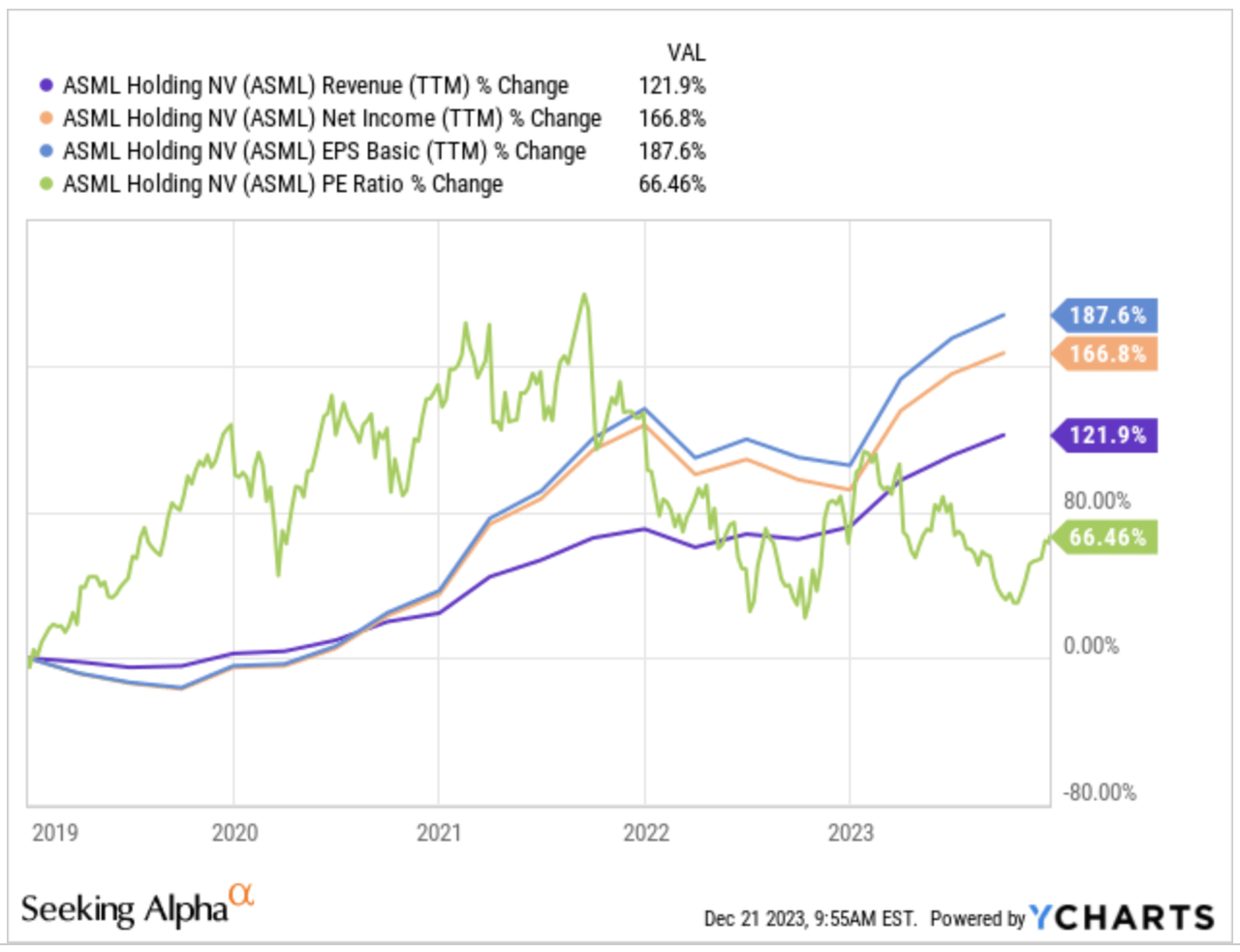

The important thing to understand here is that while the first variable (fundamentals) tends to move somewhat slowly (if we don’t include cyclical companies), the second variable (the value the market gives those earnings) can experience violent swings. Below, you can see how, despite relatively stable and improving fundamentals over the last 5 years, ASML’s PE ratio has been pretty volatile, leading to pretty significant swings in its stock price:

In short, companies rarely change, but how investors view these companies tends to change rather violently and recurrently in some cases. This is why, despite durability being touted as something only long-term investors should care about, it’s something that all investors, irrespective of investment horizons, should care about. Even if you are only looking two years out, any change in how the market views a company's terminal value will immediately affect its stock price and thus, an investor’s returns.

The good news is that truly durable companies tend to enjoy somewhat stable market perceptions. The reason is that if a company is truly durable, the probability of negatively surprising the market is significantly reduced, leading to fewer swings in perception. Take, for example, Hermes. The French luxury company has enjoyed stable fundamentals and a somewhat stable perception by the market in recent years. Of course, COVID wreaked havoc across many valuation ratios:

The result of stable and growing fundamentals coupled with a somewhat stable market perception has resulted in great returns for shareholders and, most importantly, no major negative surprises. Hermes’ stock has only dropped once more than 30% off ATH in the last decade, and that was in 2022 due to the COVID hangover:

Most of you know that I don’t view volatility as a proxy for risk. Still, I do think (and that’s basically the rationale behind Best Anchor Stocks) that a volatile stock is much more challenging to hold and can lead investors to one of the most significant risks of all: selling too soon. In short, enjoying a 15% annual return with no major downside surprises is much better than enjoying a 15% annual return in a very volatile stock. Investors should never maximize for returns but rather for risk-adjusted returns.

With this said, I believe (and this is one of the places where my investment philosophy has changed somewhat) that the best combination an investor can find is a truly durable company that the market does not identify as such. This way, the investor will have more opportunities to add to their position at attractive prices, something that doesn’t happen often (albeit it does eventually) with companies that the market does identify as truly durable.

The benefits of durability and why it can provide superior investment returns

The obvious question now is: why is durability a good trait to look for? There are, in my opinion, several reasons to focus on durability. The first one is that durability is an indispensable characteristic to enjoy “cost-free” compounding. It’s well documented that the big money is made holding a company for many years and letting it compound returns.

Many will argue that true compounding happens at the portfolio level (i.e., by the investor compounding returns rather than any given company). While I obviously agree with that observation to an extent, I also think that not many investors focus enough on the costs associated with compounding their portfolio. If I find a truly durable company and invest my money in that company, then I will compound my capital in a tax and commission-free way. If, on the other hand, I focus on jumping in and out of companies to compound my wealth, I might as well be successful, but the net and gross returns are going to vary markedly:

Your money is like a bar of soap – the more you handle it, the less you’ll have.

Durability is an indispensable characteristic to enjoy the benefits of compounding without facing too many transaction costs. With this, I am not trying to say that investors should never sell. One should sell if one acknowledges they have made a mistake or that there are better opportunities elsewhere. The only thing I am trying to claim is that looking for truly durable companies (obviously we will not be right all the time) minimizes transactions and thus portfolio management costs.

Another reason to favor durability is that time is the most significant source of optionality, and it’s tough to price. Optionality is a widely discussed topic in financial markets but is highly subjective. It refers to future revenue or profitability that doesn’t exist today but might help the company grow and improve. Probably the best example (or most famous) is Amazon’s AWS.

Of course, some companies enjoy more optionality than others (due to the nature of their underlying business), but any company has a higher chance of enjoying optionality if it’s durable. We live in a fast-changing world where companies must constantly adapt to the environment, so durable companies are likelier to…

Have a culture of reinvention; otherwise, they would not have survived for so long.

Give opportunity for further optionality to play out

Optionality is very tough to price because it’s unknown. In my opinion, it’s much better to hold companies with the highest chances of enjoying future upside caused by optionality. These companies are typically characterized by innovative cultures but also by durability. Optionality is one reason (but not the only one) that demonstrates that time is on the investor’s side.

The other reason is that durability also protects us (to some extent) from valuation misjudgments. Paying a fair price is always important, but we’ll definitely get it wrong from time to time. The good news is that investing in durable companies diminishes the probability of a permanent capital loss, even if the IRRs achieved are nothing to write home about. One can see this as the consolation of fools, but knowing that the downside is protected to an extent helps sleep better at night. Of course, we can’t protect ourselves against permanent capital loss if we pay too much of a high price. There are plenty of examples in financial history.

Lastly, besides durability being tough to price by the market, we must add that many market participants don’t care about durability due to the existing incentive system. I have explained this in several other articles, but in short, there’s little incentive for many investment managers to focus on the durability of an asset when they are “being paid” for continued outperformance. This search for continuous outperformance should technically make them focus more on what will happen in the next year or two than on how truly durable a company is. It’s a dangerous strategy because, as I commented above, durability matters even over the short term, so these managers are playing with fire.

How to assess durability

Durability is not easy to assess as we humans are not equipped with the ability to forecast the future. This said, we can look for common traits that improve our chances of finding truly durable companies.

The first of these traits is a good history. Warren Buffett used to say that if a company had a lousy past, he would be willing to miss it, and I can understand why. Investing is all about the future, but the past can teach us some valuable lessons. First of all, a company that has thrived through generations has demonstrated that…

It produces a durable good/service

It has managed to adapt to the changing times

I personally prefer #1 because it’s less subject to mismanagement than #2, but both can be very valuable. #1 resonates a lot with the concept of the Lindy effect, which I discussed in another article. Capitalism is brutal, so seeing that a company has managed to survive and prosper for a century should tell us there might be something special in it (it’s never an assurance, of course).

I don’t typically talk about stocks individually, but I think that a past of shareholder value creation is also important. Some businesses have done well, but their stocks have not done so well, meaning that the management team has not found a way to translate business returns into shareholder returns.

In short, if a company has a lousy past and does not have a good track record of shareholder value creation, and investor must be sure that this will eventually change. If the company has a good past, however, the investor should assess the probability of that continuing in the future, which is arguably ”easier.” Note that I also hold companies with a lousy past in terms of their stock but where I think things are changing (Nintendo, Diageo…). There’s nothing wrong with this, but I do acknowledge that I am “betting” against the past.

Another way we can look for durability is by focusing on industries where capacity is somewhat capped or controlled. It’s much easier (not saying it’s easy) to forecast the future state of an industry where supply is capped (due to the scarcity of a given product or due to high barriers to entry) than forecasting the state of an industry where supply is not restricted. In the first scenario, the outcome is much more in control of any given company than in the second scenario. Supply is more important in driving shareholder returns than demand, even though the market tends to focus on the latter.

Lastly, I believe that there are two key characteristics found in durable companies:

Pricing power

Solid financial positions

#1 is important to enjoy growth over long periods. It’s not really conservative to assume that a company can grow its volumes forever, but if it has pricing power, it will have an additional growth lever. Companies with pricing power typically have a strong brand, are mission-critical, and/or make up a low portion of the customers’ cost.

With a solid financial position, I am referring to truly immaculate balance sheets. Companies that think in decades tend to have minimal debt (if any) and cash-rich balances. The latter not only helps with the financial position but also positions the company to take advantage of optionality should it present itself. I know that the efficient capital structure theory suggests that companies should carry as much debt as their business model allows them to juice shareholder returns. While this makes sense, it doesn’t account for Black Swans that eventually happen over a company’s life. For example, nobody foresaw a global pandemic, but thanks to its cash-rich position, Hermes was able to not only maintain all its employees but also pay them a bonus. That will have a great impact on its culture.

Conclusion

I hope this article helped you understand why durability is such an important topic for investors, why it can provide superior investment returns, and what traits to look for in assessing it. Needless to say, capitalism is brutal, and there are not many companies with truly durable characteristics. The good news is that we don’t need a portfolio of 200 companies; 15-20 companies might just make it.

In the meantime, keep growing!

Great article. Thanks for sharing it!

Durability as a factor in quality. Thanks for the write-up! Although the image from credit suisse shows the value in the first 2 years, one of Mauboussin's research papers does say that on average investors look pretty far ahead (we usually think they look in the short-term). Can't find the reference but I'll look it up.