A Resilient Growth Industry, But Not Without Challenges

Definition, growth opportunities, competitive advantages, players, risks...

The premium subscription gives you access to all the content in Best Anchor Stocks, which includes…

All the deep dives

Recurring articles

Access to my real-time portfolio and transactions

Occasional webinars on various topics

A community of like-minded investors

A subscription the Premium + also gets you a quarterly Q&A with me to discuss anything you’d like.

If you want to know the type of content I share at Best Anchor Stocks you can read the Deere deep dive I uploaded a few weeks ago for free…

…or you can also read any of the other many free articles I have shared, just like this one!

You can also read the testimonials that existing subscribers have left. If you are a passionate and curious investor wanting to learn about high-quality companies, don’t hesitate to join Best Anchor Stocks!

Introduction

If the last three years have demonstrated one thing is that volatility is not a risk but can lead to one of the most significant risks of all: acting on our emotions. In our view, two things are necessary to enjoy worthwhile returns. The first is finding a high-quality company at a fair price (or, if one is lucky and/or patient, at a great price). The second one (many times overlooked) is the holding period. For a quality company to show its worth, it needs time, and everything that pushes us to sell out of our positions too quickly is a risk that promises to erode this holding period.

There are, in essence, two ways to mitigate this risk. The first and most important one is to understand the value of what we own. This way, rather than seeing stock price volatility as a risk, we’ll see it as an opportunity or largely irrelevant. This said, regardless of how well we know a company, it’s inevitable to come across periods when we don’t somewhat question our holdings. Doubts are natural and the world is full of unknown unknowns, but it’s how we act when faced with these doubts that’s important.

The second way to mitigate this risk might be simpler in essence: owning resilient companies in resilient industries. These companies tend to have several particularities. For starters, they don’t tend to be cheap. The market is well aware of their resilience, and therefore, ascribes a high multiple to them. There’s a common misconception that a company's valuation multiple only takes growth into account. This completely misses that the most important component of a valuation ratio is not growth but the durability of this growth and how much value a company can create along the way (i.e., its returns). Both these things are encompassed in the terminal value.

The good news for investors is that these resilient industries sometimes go out of favor. Bioprocessing or semis might be good examples of this dynamic (we have exposure to both), but today, we want to talk about another industry that we believe meets all these characteristics (resilient and out of favor): the spirits industry.

This article should serve as a quick primer for those unfamiliar with the industry, although we have discussed some of the topics more in detail for our subscribers.

Without further ado, let’s get going.

The origins of alcohol

The origin of alcohol dates back to somewhere between 6,600 - 7,000 before Christ, around 8,000 to 9,000 years ago. Giving a specific location to its origin is a stretch, but researchers believe the first alcoholic beverage came from Jiahu, a Neolithic village in the Henan province in Northern China.

We say it’s a stretch to anchor the origins of alcohol to a specific location because, around the same time, barley beer and grape wine were beginning to be made in the Middle East.

Regardless of its location of origin, what we can undoubtedly affirm is that alcohol has been among us for thousands of years. The past is never a perfect proxy for the future, but antifragility is always a common trait among resilient industries.

As one would imagine, alcohol’s survival throughout all these years has not been a piece of cake: it has faced many roadblocks through history. One of these was the Nationwide Prohibition of alcohol in the US, which lasted more than a decade (from 1920 to 1933).

Of course, the prohibition gave birth to a secondary illegal market for the product, illustrating that there was little that could stand in people’s way when it came to alcohol consumption. Despite this 13-year-long prohibition in the US, alcohol came out stronger, and the US is today the largest alcohol market in the world. This, by itself, already speaks great about the resilience of the category.

But, why has alcohol endured and grown through all these roadblocks? We will try not to get philosophical here, but the reason behind this might be the social nature of the human being. Alcohol has always been at the core of social relationships, both personal and professional, which humans have craved for thousands of years.

Man is by nature a social animal; an individual who is unsocial naturally and not accidentally is either beneath our notice or more than human. Society is something that precedes the individual.

Aristotle (350 BC)

Note, though, that antifragility is not a synonym of a good investment. A product might have been with us for centuries but it might be a poor investment because its unit economics are poor. Of course, we believe that unit economics in the alcohol industry are probably the best that they have ever been, as scale now allows incumbents to cement their competitive positions.

Before digging deeper into spirits as a category, it's important to understand why spirits is not the same as the broad alcohol category.

Contextualizing spirits in the TBA industry

Alcohol is a very broad term which is encompassed in what we now know as the Total Beverage Alcohol Industry or ‘TBA’ in short. The global TBA industry is huge, with sales of $1.6 trillion dollars expected for 2023. Beer unsurprisingly leads the industry with annual sales of around $600 billion.

The TBA industry, like many other industries, suffered a pandemic-induced hiccup due to crippled supply chains and the “absence” of the on-trade (restaurants, bars, clubs…), with the off-trade (house consumption) remaining resilient. However, like in many other industries, the hiccup was short-lived and sales have already recovered to pre-pandemic levels.

According to Statista, the TBA industry is expected to achieve a 5% CAGR (Compound Annual Growth Rate) through 2027:

As you can see in the chart above, spirits is a subset of the broad TBA industry, commanding $486 billion in sales in 2022. It’s also worth noting that the above describes sales value, not profits. We have not managed to find profit numbers, but it’s probably fair to assume that spirits makes up an even larger percentage of the profit pool due to its inherently higher margin than other categories. This is further evidenced by the current premiumization the category is undergoing.

The above categorizations have important implications to understand market shares. For example, Diageo quotes its market share at around 4.7% of the TBA industry as a reason to believe in the growth ahead. While we do understand that they are indeed a TBA player (they own Guinness (beer), for example), they mostly generate their sales and profits from spirits. We think it’s fair to assume that Diageo’s market share is larger than 4.7% in the spirits category, place where management has chosen to play in.

Considering that Diageo has moved to a more premium spirits offering over the last 5 years, it’s also fair to assume that its market share of the industry’s profit pool is also larger than its market share over the net sales value in spirits. We do think the opportunity ahead is still significant, but these nuances are important to understand where spirits companies lead, where they don’t, and how large the opportunity ahead is.

The spirits industry is further subdivided in categories like scotch whiskey, international whiskey, tequila, gin…you get the drill. Whisky is the largest category and still growing at a decent pace, but the fastest-growing category by far is currently Tequila.

Understanding to which categories and geographies large players are exposed to is also important to understand market share gains and losses. For example, Diageo has a considerable exposure to Scotch and Tequila, both of which grew fast coming out of the pandemic. This has allowed the company to gain significant market share during those years:

Where will growth come from in spirits?

The spirits industry enjoys several industry-specific growth drivers that are behind the reshaping of the portfolios of the big players. The broad TBA industry is expected to grow at a 5% CAGR over the next couple of years, but growth will be asynchronous between the different pockets, with some growing ahead while others staying behind.

Spirits taking share of beer and wine

One pocket that will grow faster than the overall TBA industry (you guessed correctly) is the spirits category. The spirits category has been taking share of categories like wine and beer for some time now, and large players and industry experts expect this will continue:

A premiumizing spirits category

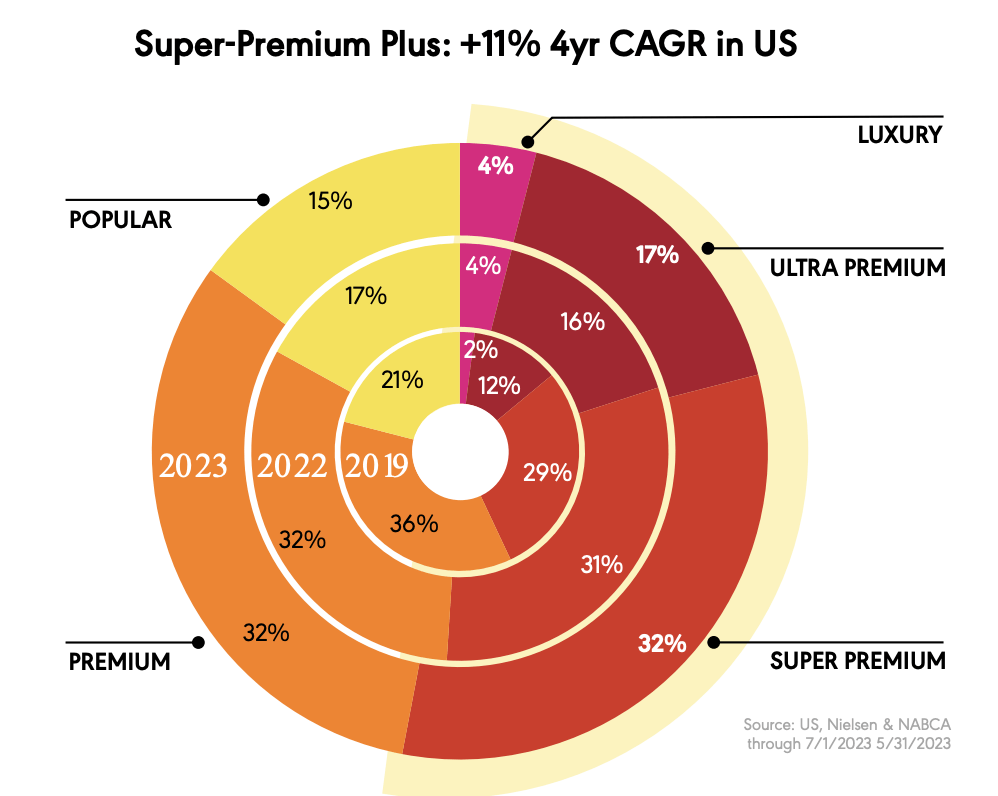

Inside the spirits category, higher-priced products are taking share of overall spirits sales. Most importantly, these super premium+ and premium spirits command higher margins, taking market share from the profit pool at an even faster rate:

The premium, super premium+, ultra premium, and luxury categories now make up 85% of total spirits sales vs. 79% barely three years ago. Of course, skeptics will point out that we’ve lived through easy economic times, which has favored the rise in premium categories. Many investors are worried about a potential trade down if the economy were to worsen, which is a fair concern but one that’s not coming to fruition. According to Diageo’s management, despite the worsening economic situation in some geographies, consumers are not trading down:

Like I said, you certainly are seeing some heat in kind of that super premium plus tequila as well as ultra, but we're not seeing kind of a premium to mainstream slide really anywhere.

Source: Debra Crew, Diageo’s CEO, during the most recent earnings call

One of the reasons for the resilience of the premium categories is that, despite these being expensive products, they make up a low portion of customers’ budgets. In fancy words we could say that spirits constitute an affordable luxury. The median yearly spending of a US household in spirits is still fairly low:

What I would just spend a few minutes on is just talk about the affordable luxury nature of our category. And I'll use the U.S. as an example because I think it really brings it to life. Premiumization trends, as you've seen in the presentations, are really strong. But when you look at it from a household standpoint, the typical U.S. household is spending $17 a month on spirits. Half the households buy spirits. So for those who buy spirits, they're spending about $35 a month. That's $1 a day.

Source: Ivan Menezes, Diageo’s former CEO, during the 2021 Investor Day

We could undoubtedly see some sort of trade down if the economy worsens and the on-trade weakens with people trading down in the off-trade. This would have important implications for players that have premiumized as they could prove to be less resilient than what they once were. The rationale is that these players have been disposing of value brands, which typically do better in tough economic environments. It’s also true, though, that premiumization entails higher margins, so it’s difficult to pinpoint a scenario where the profits of these companies suffer significantly even if volumes fall.

But, what’s driving this premiumization? Healthier lifestyles are playing a role. Many people are drinking less but better now that health has become a primary consideration. This trend will probably translate into less volume growth and more growth coming from price/mix as large corporations push to premiumize the category. These dynamics are already evident for some companies like Diageo, where price/mix has played a more important role in growth in recent years:

Demographics - Increase in the LDA population

The industry also enjoys favorable demographic trends. The legal drinking age (LDA in short) population is expected to increase meaningfully over the coming years, especially in countries such as India:

And in India, the LDA population is growing on average by 20 million people a year with good GDP growth and with as well a strong urbanization rates, which is what we'd like to call the perfect cocktail for our spirits category.

Source: Alexandre Ricard, Pernod Ricard’s CEO, during Investor Day

A larger LDA population logically translates into more potential customers for the spirits companies.

Emerging countries

All of what we have discussed above applies globally, but we would be fools in believing all geographies are in the same maturity stage. For example, premiumization and the rise of the LDA population is much more advanced in the US than in India, China, or Africa, as these countries are still early in their transitions with a growing middle class.

This is precisely why large spirits companies have “gone global.” A good chunk of future growth might come from the three emerging geographies mentioned above, all of which are difficult to tackle due to complexity and regulation. Complexity and regulation might sound like roadblocks, but they constitute important competitive advantages for the large corporations.

All in all, the spirits industry undoubtedly enjoys growth drivers going forward, driven by share growth, premiumization, and a larger customer base. How companies in the industry will gain/lose market share will depend on their positioning across spirits categories, price points, and geographies. Being exposed to specific niches in the industry might turn out to be a good choice, but it’s above the risk tolerance of most companies.

This said, growth is not enough to enjoy worthwhile returns. Attractive growth can be competed away by new entrants if entry barriers are low, but these are pretty significant in the spirits industry. We will first discuss the industry-specific competitive advantages that benefit the incumbents, and we will later discuss what we believe it takes to win in the industry.

The inherent moats in the spirits industry

Before going over what we consider the most important industry-specific competitive advantages, you must be aware that some of these apply only to some categories. With that in mind, let's review these.

Location - What’s behind the name?

Some spirits categories are capacity-constrained due to the specific location where they must be manufactured. Good examples here are Scotch and Cognac, especially the latter. Scotch whiskey has to be manufactured and aged in Scotland, or else it can’t receive the “scotch" adjective. This doesn’t mean there’s no whiskey made elsewhere, it’s just that it can’t be called scotch. However, the most extreme example of this competitive advantage at play is probably Cognac.

To be considered Cognac, grapes must be harvested in a very small region in France called (you guessed correctly) Cognac.

If this is not the case, then the liquid can’t be called Cognac and receives the name Brandy. This subtle difference makes it lose a good deal of its status. As one would imagine, with Cognac dating back to the 16th century, all of the production capacity has already been taken. 4 Cognac brands are responsible for roughly 9 out of 10 Cognac bottles consumed worldwide:

These companies control most of the production and distribution, so it’s virtually impossible to enter the market without their “permission.”

Scotch enjoys somewhat similar characteristics, but as Scotland is larger than the Cognac region, one could argue that opportunities for capacity expansion are still present even if inmaterial. Scotch dates back to the 15th century, so the incumbents have also managed to control this capacity to increase entry barriers.

Tequila might follow the steps of the categories above. However, its popularity only dates back to some years ago, meaning that capacity is still growing quickly and is not reserved to a handful of companies. To be considered Tequila, the liquid must be elaborated with Blue Agave harvested from certain states in Mexico.

The Mexican government is expanding agave capacity to correct the imbalance between demand and supply, but there’s only so far capacity expansion can go. If Tequila ends up being as popular as Scotch, we might see a similar scenario play out where capacity eventually stagnates and incumbents own most of it.

Of course, what I have just discussed does not apply to all categories. Spirits such as gin and vodka can be made anywhere in the world and require no aging whatsoever, lowering the barriers to entry significantly.

Aging - You can’t buy time

Aging refers to the maturation processes of some spirits and presents another significant entry barrier to the industry. There are two types of aging. The first type is required aging. Some categories make aging a requirement before the product can be marketed.

For example, to be considered Scotch, the liquid not only has to come from Scotland, but it must also be matured for a minimum of 3 years in oak casks:

This means that a new entrant to Scotch will have to wait at least three years to sell their product, incurring losses in the meantime. The other option is to purchase aged liquid directly, but we don't think that making a business dependent on third-parties is the best way to go here.

The second type of aging is voluntary aging. There’s a low limit in aging for some categories (3 years in the case of Scotch), but there’s never an upper limit. An aged product is considered higher quality than a non-aged product and is typically sold at a significantly higher price point. Incumbents have aged some of their liquid for decades, making it an impenetrable entry barrier for new entrants because you can’t buy time.

It’s rumoured that Remy Cointreau’s most luxurious Cognac bottle includes some drops of 100-year-old liquid. It’s virtually impossible to compete against such products unless one has been in the game for a very long time. Evidently, aging, and its connection to product quality, benefits the incumbents. Despite being in advantaged position, incumbents have not rested in their laurels and are increasingly investing in maturing inventory to protect their competitive positions and fuel growth.

Another beneficial characteristic of aging is that it protects spirits companies from inflation. Harvest and production costs for aged liquids were incurred years ago but the liquid is sold at current prices. Yes, there are storage costs along the way, but the most important cost in production is energy and there’s very low energy consumed during the storage phase.

Harvesting can also pose a significant entry barrier in some categories. Take the example of Tequila. Agave takes 6-7 years to mature and the cycle must be restarted after the harvest. This means that if a new entrant wants to start from scratch, it will take them at least 6 years just to harvest the Agave. Of course, this is not applicable today because one can buy agave from third-parties, but what if this capacity is in the hands of the incumbents one day?

It’s also important to understand that investing in maturing inventory is a trade-off: it strengthens the competitive advantage and growth prospects over the long-term, but it negatively impacts current cash conversion due to higher inventory.

Brands - Centenary and antifragile

Brands can also be considered some sort of entry barrier to the industry. Some brands are more than three centuries old and have always been front and center in the consumer’s mind. The fact that these brands have endured centuries (including regulatory bans) speaks great about their antifragility.

However, this is undoubtedly the least tangible competitive advantage we see in the industry, especially because times might be changing and brand strength might be starting to lose some relevance (more on this later).

What does it take to win in spirits?

Industry-specific moats are great because they increase the entry barriers to the industry. This means incumbents are somewhat “safe,” but what does it take to win in the industry? Before starting our research we believed the crucial differentiating factor between incumbents were the brands, and even though this is indeed an important differentiator, it’s not the most critical one. Let me start with what we consider the most critical competitive advantage for any spirits company: scale.

Scale - The core of the moat

It’s common knowledge that, as a company gets larger, it finds more roadblocks to grow due to diminishing marginal returns. While we are sure many of you understand and agree with this concept, we believe scale is not only necessary for resilience in spirits but also to achieve worthwhile growth. After all, growth is capped by category growth. No matter how big or small a company is, its growth will inevitably be a function of the categories and countries it’s exposed to. Take, for example, the cases of Pernod Ricard and Diageo.

Diageo recently guided for organic sales growth of 6% (at the midpoint) through 2025, whereas Pernod Ricard has guided for growth of 5.5% (at the midpoint) through the same period. It’s true, though, that Pernod Ricard’s management believes they will be able to achieve something close to the high point of guidance, around 7% CAGR.

Pernod is indeed expected to grow slightly faster than Diageo, but the only caveat here is that Diageo has more than 1.5x the sales of Pernod. Of course, the portfolio’s of both companies are not entirely comparable, but that’s precisely the point we are trying to make here. Scale does not seem to have that big of an impact on growth, while it’s highly beneficial across two spectrums: distribution and marketing. Let’s start with the former.

Distribution is a key competitive advantage in the spirits industry. We can look at it in two ways. Sometimes the distribution advantage is local (like in the US) but often times it’s global. Let’s start with the the local distribution advantage talking about the US.

The US spirits industry follows a three-tiered distribution system, which bans spirits companies from selling directly to consumers. Spirits companies must sell to distributors, who later sell to retail shops, who ultimately sell to the end consumer:

This basically means that relationships with distributors are crucial to having a good route to consumers. As one could imagine, distributors are more willing to distribute the products from the proven companies, as they know the probability of selling all of their stock is pretty high with these. Unproven brands take time to gain leverage.

Relationships between spirits companies and distributors are so strong that they even share marketing expenses. Distributors and large spirits companies jointly roll out marketing campaigns and product placement, a privilege that smaller brands are unlikely to enjoy.

If we go outside US borders, distribution is also critical to scale globally. Alcohol faces diverging and dynamic regulation worldwide, increasing complexity and making it almost impossible for a company to run international operations locally. The large corporations have established themselves with local offices in countries such as India and China, unreachable for smaller players who have not established such offices. Note that alcohol distribution happens through restaurants, bars, and retail shops, all of which require a good understanding of the local economic landscape.

Both of these distribution advantages not only strengthen the moat but also make acquisitions very appealing for the large corporations. What might seem like an expensive looking price for a local company can turn out to be a bargain once the acquired brands are scaled globally. Simply put, as local brands understand their limitations to scale globally, the large companies can offer them an expensive looking price while still delivering good ROI (Return On Investment).

Note that this distribution advantage also tames the fears of celebrity brands as a terminal risk. Many people claim that celebrities are scaling their brands and eating into Diageo’s or Pernod’s market shares, but what they are ultimately doing is creating an M&A pipeline for the large players. We have trouble seeing how Dwayne Johnson (for example) will be able to scale his brand worldwide without finding significant roadblocks.

A good example of this is Diageo’s purchase of Casamigos (George Clooney’s Tequila brand). Diageo purchased it in 2017 for $1 billion, which Morgan Stanley estimated was a 20x sales multiple, pretty steep.

Casamigos is now one of the company’s core sales drivers, has improved margins and has started international expansion. We had never heard of Casamigos in Spain before Diageo purchased it but it's now the name of a bar in one of the most famous ski resorts here (Baqueira Beret).

Another good example where these scaling dynamics are evident is Pernod’s acquisition of Lillet:

When we acquired it in 2008, Lillet was roughly a 50,000 case brand. It’s now 1 million cases.

What we are trying to illustrate here is that acquisition multiples can be a bit misleading because the metrics of target companies are oftentimes capped due to distribution and marketing limitations that evaporate once they fall into one of the large companies.

Now jumping to marketing. Let’s start with the obvious one: scale allows large companies to deploy more absolute dollars on advertising while remaining more profitable. This tale is as old as time.

The most important, and probably underappreciated, advantage of scale in marketing is the access to data. People around the world are increasingly interacting through digital channels and the large players are using this data to improve marketing efficiency:

And here’s the beauty of it, you’re not buying expensive mass media. You’re buying cheaper personalized media. That’s how you can afford to spend against more brands even though you’re spending circa 16%, right?

Source: Pernod Ricard Investor Day

The above leads to two possible paths. Under the new marketing paradigm, large companies can…

Spend the same amount in marketing to accelerate growth

Spend less on marketing for the same level of growth to expand margins

Most companies in the industry are taking the first approach, probably to widen the gap with the players who don’t have the same absolute dollars to spend.

Most importantly, this vast access to data gives these companies foresight to anticipate trends. Diageo made its first important acquisition in Tequila in 2014 (Don Julio), before it was trendy. According to management this was thanks to their ability to look round the corner thanks to vast customer data, which allowed them to position the portfolio beforehand. With large companies positioning their portfolios in advance of trend shifts, the gap with smaller players will probably get larger, not thinner.

The importance of diversification

Diversification, both in category and geography, is also a key trait of any resilient company in the industry. Category growth is fickle and is continuously shifting. Tequila might be the fastest growing category today, but this might change in some years. For example, gin and vodka had their “supercycles” but now growth is moderating somewhat. This means that having a good assortment of categories is key, not only to protect oneself against this volatile consumer trends but also to provide leverage in the relationships with retailers and the on-trade.

Something similar applies to geographical diversification. Any company heavily exposed to one single geography can prove to be less resilient than it looks when the economy goes south there or when that geography suffers destocking dynamics.

Geographical diversification is also key for growth, not only resilience. We believe that companies without significant exposure to India, China, or Africa might not enjoy the same growth going forward than those that are. Industry growth drivers are present globally but are obviously more nascent in these geographies as the middle class continues to grow fast. To be honest, we think exposure to these countries is good for pretty much any company worldwide, regardless of industry.

Who participates in the market and what’s going on?

The spirits industry is pretty fragmented, although there are a couple of global players currently consolidating it. Consolidation is a consequence of what we discussed above: there are thousands of spirits brands across the world, but only a few global corporations with the necessary infrastructure to scale these globally.

The largest player in the market is Diageo, followed by Pernod Ricard at roughly half the size. There are other large global corporations such as Beam Suntory (owned by Suntory Holdings Limited of Japan) and Brown Forman:

These companies are similar in that most of them are diversified across spirit categories and geography, but there are nuances. For example, Pernod is not huge in Tequila, while Diageo is. Pernod has direct exposure to Cognac through Martel, while Diageo has indirect exposure through its 30% stake in Moet Hennessy:

Then one can also find other large corporations focused in certain parts of the market. For example, Remy Cointreau’s management has talked about diversifying across spirits categories, but the company is still significantly exposed to Cognac (around 70% of its sales). Another example here would be Campari, which owns brands across many categories but is known for its strong lineup in aperitifs.

What’s going on in the industry right now?

Most of the companies in the industry have significantly lagged the market this year:

So, what has been the cause of this underperformance? It’s always a challenge to guess what moves markets over the short term, but it seems this year’s poor performance has been caused by destocking issues in the US. These arised after a volatile environment caused by the pandemic. As most of you know supply chains got challenged, and while demand from the on-trade also subsided, the off-trade remained strong, causing a supply-demand imbalance. This supply-demand imbalance caused industry-wide shortages, leaving distributors out of stock.

To avoid something similar happening in the future, distributors restocked as soon as supply came back and incentivized by the high demand stemming from the reopening of most countries. Surging tourism, travel, and social occasions all were behind the surge in demand, with the market growing ahead of historic rates. Restocking was taken to the “extreme”, and inventory levels across distributors grew above historic norms.

Now that demand is somewhat correcting in the US, these distributors are eating into their inventory to bring their inventory levels back to normal. Diageo’s management recently claimed that inventories are now back to historic averages and that they don’t expect the destocking to significantly impact FY 2024 numbers:

Destocking has been a headwind for the spirits companies exposed to North America, geography where growth has significantly slowed this year. As spirits companies tend to be geographically diversified, they managed to grow nicely despite these headwinds. Diageo grew sales organically 6.5% year-over-year despite flat growth in North America, which made up almost 40% of its FY 2023 reported sales. This just demonstrates the importance of diversification.

Diageo’s management also argued that countries like Brazil are running at higher inventory levels than usual, so we might see destocking shift to other geographies in FY 2024. If North America comes back in 2024, this should not be a point of concern. Needles to say that if Diageo is impacted by destocking dynamics, it’s likely that other companies are too.

Destocking undoubtedly seems a short term headwind which has dragged down (or rather normalized) these companies' valuations. However, despite how resilient the industry is, there are risks which might impact the long-term thesis. Let’s go over these.

Risks

No industry is risk-free and the spirits industry is no different. Through its 9,000 years of existence, alcohol has demonstrated being a resilient industry that has managed to even survive industry-wide prohibitions. But what risks does the industry face today?

(1) Brand loyalty might be decreasing

Something that seems pretty obvious is that brand loyalty is decreasing in the spirits industry. Customers once drank the same spirit from start to finish (death), but newer generations have proven to be more open to trying new things. In the words of Pernod Ricard’s CEO:

It was one of the biggest evolutions in the spirits industry in the past 15 to 20 years, is the consumer is no longer as loyal to a brand or to a category as he or she was in the past.

So, what changed? It’s difficult to pinpoint a specific event that caused this shift, but surely the rise of social media has something to do with it. The cost to advertise has gone down dramatically thanks to social media, allowing smaller brands that didn’t have access to traditional advertising to advertise. Some decades ago only the large corporations like Diageo and Pernod had enough money to invest in mass traditional media, but now the playing field is getting level, or is it?

While access to cheaper marketing is allowing smaller companies to advertise, it’s also helping the large companies that generate vast amounts of data go direct to consumer in a personalized manner. These companies are still spending billions on marketing, it’s just that now they expect to get a better ROI out of it. It all goes back to the scale advantage we discussed earlier.

It’s true, though, that lower brand loyalty can have two potential ramifications. The first one is that large corporations might have to spend money continuously to keep century-old brands relevant. The second ramification is that the smaller brands might be getting more expensive due to increased relevance thanks to cheaper ads. With large companies consolidating the market this can potentially translate into lower IRRs.

Fortunately for these large corporations, distribution requires infrastructure that is unlikely to face disruption from technology as marketing did: if you want global distribution the only path is to spend the dollars.

(2) Regulation - Following tobacco’s footsteps?

Regulation is of course an issue here too. Alcohol is seen somewhat similarly to tobacco in that it can cause an addictive disease known as AUD or “alcohol use disorder.” People who suffer AUD are commonly known as alcoholics.

According to this report, AUD affected more than 8% of males and 1.7% of females in 2016 worldwide, with percentages varying across countries:

AUD is not only dangerous as a standalone condition but it can also lead to other diseases. With healthcare costs rising almost everywhere, governments have become increasingly wary of alcohol abuse and heavily tax the product. Besides higher taxation, governments are also targeting the awareness of the population by actively communicating the drawbacks of alcohol consumption, leading people to lower their alcohol consumption.

This said, the trend of “drinking less but better” is not new in the spirits industry and companies have been premiumizing their brands for quite a long time in response. We don’t think it would be very worrying if volume goes down as long as companies manage to compensate this drop in volume with higher prices. We can’t deny, though, that increased regulation is a risk in the industry as it could challenge alcohol distribution and customer perception.

Spirits companies, for example, could face a similar fate than tobacco companies which were forbidden from advertising some years ago. This would be somewhat beneficial for the big guys because they would not face the threat of smaller brands eating into their market shares. On the flipside, it would make the consolidation runway shorter, as large corporations would not be able to put marketing dollars behind newly purchase brands.

We don’t think we’ll see the spirits industry suffer the same fate as tobacco, though. While tobacco companies have been somewhat “slow” rolling out healthier products, spirit companies have amassed talent from the tobacco industry and are already investing significant sums into low or non-alcoholic beverages. It's also worth noting that there's a less addictive nature in alcohol than in tobacco, which might ease some regulator concerns.

(3) The potential impact of weight-loss drugs

Another (more recent) risk that has arised for the spirits industry is that of weight-loss drugs. Companies such as Novo Nordisk have made significant advancements in the treatment of obesity through GLP-1 drugs (won’t get into the technicalities here), namely Ozempic and Wegovy. Until here, all good because these drugs should impact food consumption only, right? Not so fast! Some studies have shown these drugs can also have potential implications for alcohol consumption:

Studies in rodents and non‐human primates have demonstrated a reduction in intake of alcohol and drugs of abuse, and clinical trials have been initiated to investigate whether the preclinical findings can be translated to patients.

There are still no definite studies on humans, but Morgan Stanley recently conducted a survey and came out with the following findings:

A survey conducted by Morgan Stanley’s AlphaWise research unit found that people consumed 62% less alcohol while taking weight loss drugs. Among those consuming less, 22% said they stopped drinking alcohol entirely.

According to the National Institute of Health, around 42% of the US adult population is obese, so these findings (if true) can definitely negatively impact consumption in this geography. It’s still too soon to understand how this will play out, but there are already several apparent nuances. Let’s go over them.

Nuance #1: Is it beer or spirits?

Morgan Stanley’s survey indicates that many people consumed less alcohol when taking weight-loss drugs, but they didn’t specify whether this was in beer, spirits, or in both. This might appear to be a meaningless difference, but it isn’t.

Beer makes people feel full, something that’s directly targeted by GLP-1 (as it is a weight loss drug). Spirits don’t have the same effect in satiating drinkers, so the lower consumption referenced in the survey might be more applicable to beer than spirits. This is an important detail considering that most spirits companies are not exposed to beer. Diageo is, but to Guinness, which is a different beast than beer that’s sold at high volumes worldwide.

I have a close family member who is taking Ozempic. Their beer consumption has gone down materially, but they have not seen an impact on their spirits consumption. This brings me directly to the next point.

Nuance #2: Do we drink alcohol because we crave it or because it’s a social activity?

GLP-1 apparently targets what makes us “want” alcohol, not just its intake. This means that people who take Ozempic and Wegovy will technically not crave alcohol consumption. Here we want to bring up a question: is alcohol what’s important, or is it the context in which people drink it?

It’s tough to separate alcohol consumption from our social experiences (or as Pernod calls it “conviviality”), meaning that what’s important maybe it’s not alcohol but the occasion. It’s tough to say no to a cocktail when everyone is having one, because people don’t want to feel left out. We know this might sound like a bit of a stretch, but the good performance of recently released 0.0% alcoholic spirits seems to confirm this theory. It’s worth considering that many people might drink alcohol because they like it or because they want to feel included in a social event, rather than because they crave it. Food for thought.

Nuance #3: Obesity across geographies

Another thing worth considering is that obesity is not a problem of the same magnitude in all geographies. There are obese people everywhere, but it’s a much more critical problem in countries such as the US than in Europe, for example. The worldwide obesity rate is around 13%, much lower than that of the US at 42%.

Ozempic and Wegovy have the potential to materially impact alcohol consumption in the US, but with many of these companies geographically diversified, it’s a stretch to think they can have a material impact to global alcohol consumption, at least yet.

Nuance #4: Overlap with diabetes

There’s a strong overlap of the obese population with those suffering diabetes. This means that Ozempic and Wegovy might be taken by people who were not "great" alcohol consumers in the first place. Consider that alcohol intake is already significantly reduced in type 2 diabetics, 80% of which are overweight or obese.

To this, we have to add that there are still plenty of uncertainties surrounding weight-loss drugs. How much time will people have to have them? What are the long-term impacts of these drugs? We guess we'll find out more as time goes by.

All in all, it does seem like weight-loss drugs such as Ozempic and Wegovy can potentially impact alcohol consumption, although there are nuances that we should be aware of. These nuances should make us wary of taking one side or the other too early into this story. Note that spirits companies are already positioning their portfolios to rely more on premiumization than volume and have rolled out low to no-alcohol drinks. Did they see this coming, or was it due to regulatory concerns? Tough to know, but the strategy does seem to insulate them somewhat from weight-loss drug concerns.

Conclusion

We hope this article helped you understand the spirits industry more in detail and why it has the potential to be a resilient and growth industry.

In the meantime, keep growing!

Just finished reading this excellent work.

And just subscribed for 1 year of Best Anchor Stocks.

Full disclosure: the discount will be re-invested in some Lagavulin 16 y

Thanks for the great article - it is indeed very helpful. One question though - and forgive me if it is a stupid one - how exactly can producers target their advertisement if they are not allowed to sell directly to consumers? As you have pointed out above, this applies to the US which is not the centre of the world, but could it be a limitation in other markets and specifically India/China/Africa? Thanks a lot in advance for your time.