A Recessionary and Tariff-driven World

What It Would Mean for My Portfolio (Part 1)

If you’ve followed my work for some time, you’ll know I don’t make macro or geopolitic calls/forecasts (even though I reserve the right to have an opinion). This is not based on the belief that macro or geopolitics don’t matter (they do) but on the belief that these variables can’t be forecasted accurately and repeatedly. As I acknowledge my inability to predict these, I try to correct this “flaw” by investing in companies that are, to an extent, protected from adverse macro and geopolitical scenarios (and no, I am not referring to hedging my portfolio against World War III!).

This article is the first of a two-part mini-series and reviews how a recessionary and tariff-driven world might impact the companies in my portfolio (i.e., in the Best Anchor Stock portfolio). I’ll review the companies individually and will grade them on a scale of 1 to 5 according to how protected I believe they are (5 being very resilient against a recession and tariffs). Before jumping right into it, I thought it would be a good idea to lay out what I will focus on when conducting this exercise. In my view, we can understand how a company would fare during a recession using two main methods:

Understanding how mission-critical its products/services are (one can think of this as the qualitative method)

Looking back at past recessions to understand how the company fared back then (one can think of this as the quantitative method)

#1 is somewhat subjective but surprisingly less “challenging” than #2. Even though you might think of #2 as simply looking at how a company fared through the Global Financial Crisis (the pandemic is not really the recession I am trying to assess here), the reality is much more nuanced. The fact that the last global crisis took place more than 15 years ago brings several challenges, for example:

The company's composition might be entirely different today (in product, geography, or even business model) than it was back then. Companies evolve over time

The growth runway is probably different today than it was back then. A company might have been growing throughout the GFC because it was much less penetrated across its markets

Reported growth rates during the GFC might be entirely different from organic growth rates (which is what we should care about to understand resilience)

The company might not have been publicly traded back then

…

While we can correct for some of these flaws by doing some more “in-depth” work, the reality is that the GCF period is unlikely to be a perfect proxy of the next recession. This made me realize that what I am ultimately trying to do with this exercise is NOT to understand how a business would shrink or grow through a recession but whether the business would be able to survive a recession and invest countercyclically through it. While the former (growing through a recession) is important, the latter is much easier to forecast as it would likely be the defining factor in an unprecedented recession.

A business might shrink significantly during a recession but still generate enough cash to ensure survival and countercyclical investments. The good news for long-term investors is that during recessions, the market tends to throw the baby out with the bathwater, creating opportunities even in companies that are at no risk of disappearance and that will come out stronger on the other side. A rare thing occurs during such periods: even high-quality resilient companies go on sale as the market goes risk-off.

Another reason to be relaxed if you hold cash-generative companies through a recession is that these can significantly shrink the share count at more attractive prices. All this said, one thing can be said for sure: if we go into a deep recession, I can assure you that not many things will look cheap even though they will be (that’s why this “game” is tough). Bear cases will look as realistic as ever, and everyone will start thinking that the sun will never shine again.

Without further ado, let’s start with the first company.

1) Constellation Software

Constellation Software was publicly traded during the global financial crisis. This means we can go back and look at how the company fared during a recessionary period. The only thing we must be careful with is that Constellation is an acquisitive company, so we must dig a bit deeper to understand how the underlying business was performing. Constellation’s organic growth evolved as follows during the GFC:

2008: +5%

2009 (excluding the acquisition of PTS): 0%

2010 (excluding the acquisition of PTS): +2%

2011: +10%

Based on the above, it doesn’t seem like Constellation had any trouble weathering the recessionary period. This resilience makes sense because Constellation is a diversified conglomerate of VMS businesses, and these businesses tend to have several particularities that shield them from a potential recession. I’d highlight two:

It’s mission-critical for its customers (i.e., customers need their software to continue operating regardless of the demand level)

It tends to make up a small portion of their total costs

These characteristics translate into VMS probably being down in the list of priorities when it comes to cost cutting. They also give Constellation pricing power in favorable times.

The interesting thing about Constellation is that it can also benefit from a recession (potentially) through two means. First, valuations of VMS businesses might come down in recessionary periods. Being an acquisitive company that generates significant cash flows even throughout recessions (due to its negative working capital characteristics and resilience), the M&A pipeline might increase significantly. The second reason (which was likely not present during the GFC because Constellation did not lever its balance sheet) is that interest rates tend to come down during recessions, making financing cheaper for Constellation to pursue deals. Lower interest rates should make deals more attractive when financed with debt (all else equal).

The only drawback I can find to the rationale above is that Constellation tends to acquire businesses from founders who are only willing to sell to a perpetual owner. These founders are unlikely to sell a good company during a temporary bump, so the pipeline of small and mid-sized businesses might contract somewhat. The good news is that Constellation has been increasingly leaning into acquisitions in public markets (those made by Topicus) and special situations (like carve-outs), which might indeed become more appealing during a recessionary period.

I don’t think there’s much to worry about regarding tariffs, either. Constellation sells software which is not subject to tariffs (it’s not a physical good). A trade war can have an indirect impact on the company through troubled customers, but let’s not forget that Constellation’s customer base is also very diversified.

For the reasons outlined here I’d give Constellation a grade of 5/5 regarding resilience against a recession and a tariff-driven world.

2) Nintendo

One would think that Nintendo is heavily exposed to both a recession and a trade war. Let’s think about it logically. Nintendo sells discretionary products (mainly gaming-related) that should (in theory) get cut early into a recession. While this rationale makes a lot of sense, it’s inconsistent with history. Nintendo’s yen-denominated revenue grew significantly during the Global Financial Crisis:

The revenue chart requires context, though. Nintendo had launched two of its best-selling systems (the DS and the Wii) going into the recession, which evidently helped the company weather the storm. This, strange as it sounds, might be a good proxy of what might happen this time around (note that this article assumes we get a recession soon). Nintendo is preparing to launch the Switch 2 this year or early next year, and while many believe that launching a console into a recession would be a terrible thing for Nintendo (I was in this camp, too), the past seems to demonstrate that the company’s fan base can defy even the most optimistic expectations.

Nintendo’s customers have been waiting 8 years for new hardware and I can see a scenario where a recession doesn’t weigh as much on demand. There’s an important caveat here, though: the Switch 2 is not a breakthrough hardware like the DS or the Wii were (it’s basically an improved Switch 1). This might make some fans delay their purchase if a recession were to hit as they wouldn’t be getting something completely “new”.

It’s also worth noting that the economics of purchasing the Switch might make quite a bit of sense for fans. Let’s imagine the Switch 2 retails for $400 and Nintendo doesn’t release the next hardware system for 8 years. This means that the Switch 2 would cost around $50/year. It’s probably not a cost that would deter many Nintendo fans from buying the Switch even if a recession were to hit. The only problem here is that one could argue that Nintendo’s fan base today has a lower “die-hard” fans proportion than it did during the GFC. The popularity of the Switch has resulted in massive growth in Nintendo’s customer base and some of these might not be willing to make the discretionary purchase during a recession. The past experience definitely “puts to rest” some fears around Nintendo potentially launching the Switch 2 into a recession; it would not be the first time and it played out well.

Tariffs is an interesting topic for Nintendo because, according to some sources, the significant drop the stock experienced during the past few weeks was driven by tariff fears. The rationale is that inbound tariffs to the US could potentially increase console prices and make them “unaffordable.” This makes sense, but it misses a couple of things. First, I believe that tariffs would not have an extreme negative impact on Switch 2 demand, although they’d be overall negative. The second, and most important thing, is that Nintendo started diversifying its manufacturing from China to Vietnam in 2019 precisely to mitigate the impact of future trade wars. This strategy would probably come in handy if the China/US trade war intensifies as the US could be served from Vietnam.

The other thing I’d note here is that, according to some reports, Nintendo has been building inventory of the Switch 2 in anticipation of the release. I don’t know if the company is doing this, but management could potentially “front-run” tariffs by storing this inventory in the US. Lastly but very importantly, we should not forget that tariffs would not impact software, and software is Nintendo’s main profit driver. Sure, hardware is a physical good and would definitely face tariffs should these be implemented, but it’s a one-time sale and one that Nintendo makes little money on; the big money is made on software.

All this said, Nintendo’s underlying business definitely doesn’t fall into the “recession and tariff proof” camp inside the portfolio. I am optimistic that the launch of a well-awaited Switch 2 should tame the impact of any negative environment, but the truth is that it’s definitely better to launch a new hardware system in a favorable economic and trade environment.

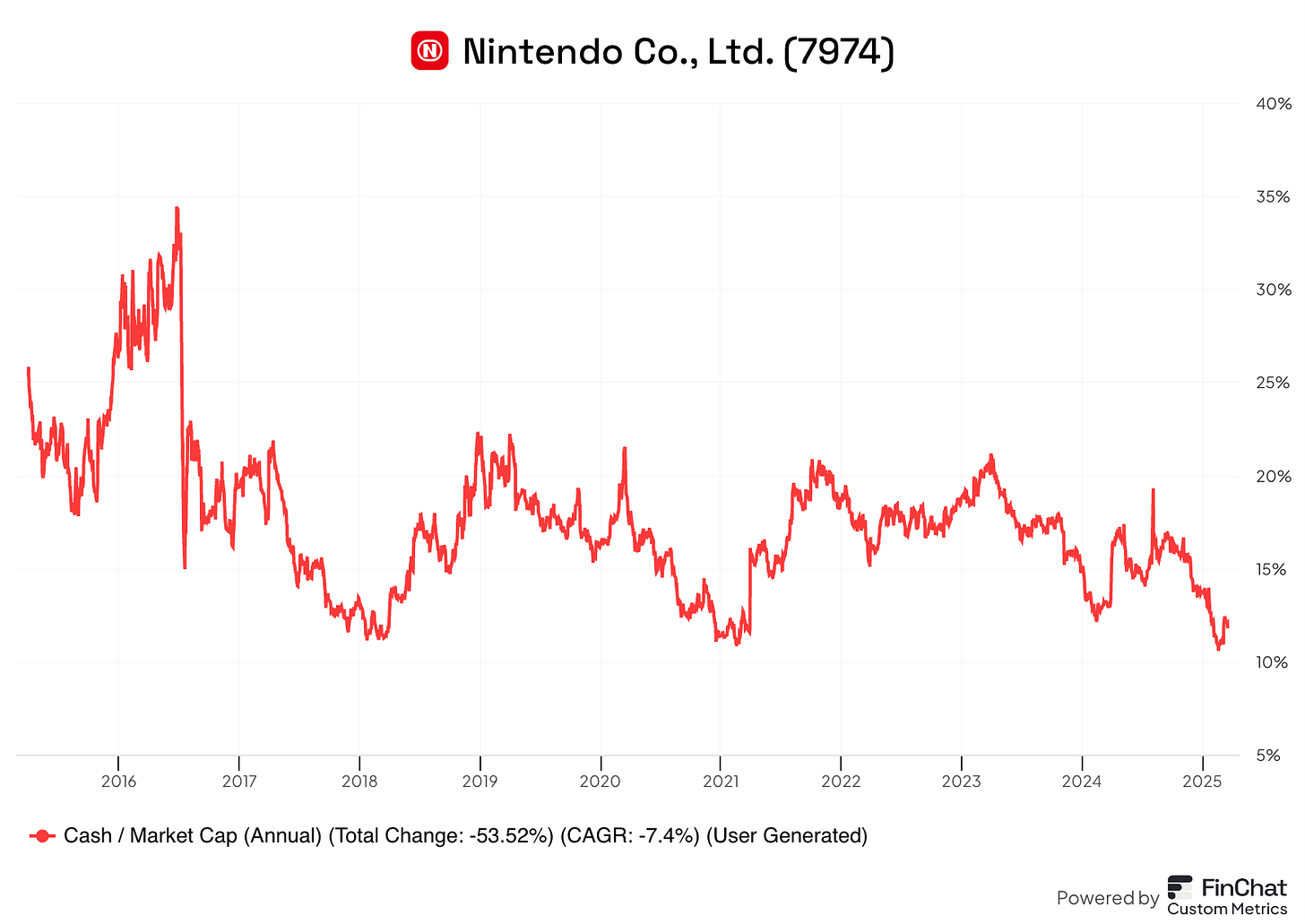

Now, while the underlying business might be impacted by a recession, I don’t think Nintendo “the company” would. The reason is simple: the company has no debt and a substantial cash position. Just for context, Nintendo’s cash position is currently hovering around 12% of its market cap (thank you, Finchat custom metrics):

Management chose to strengthen the balance sheet after the unsuccessful launch of the Wii U (the launch of the Wii U might have been Nintendo’s self-inflicted recession). The company definitely errs on the conservative side of things regarding capital structure, and while this might seem like a waste of resources when things are going well, I anticipate it will calm investors if the sea gets rough.

Despite Nintendo being well protected against a recession and a trade war, I wouldn’t call the company recession proof and would give it a grade of 3.5/5.